Mar 08, 2024

By Fisayo Okare

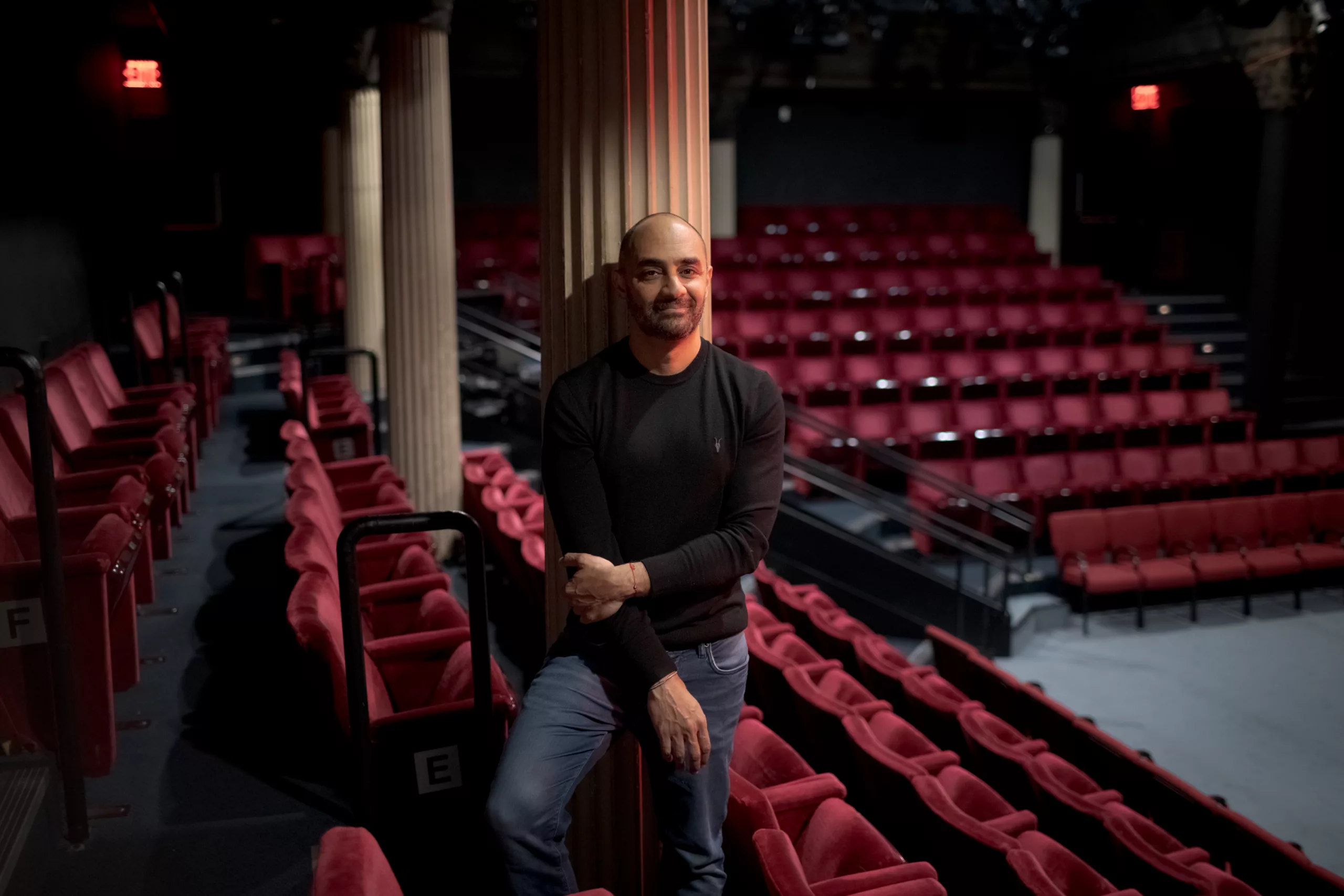

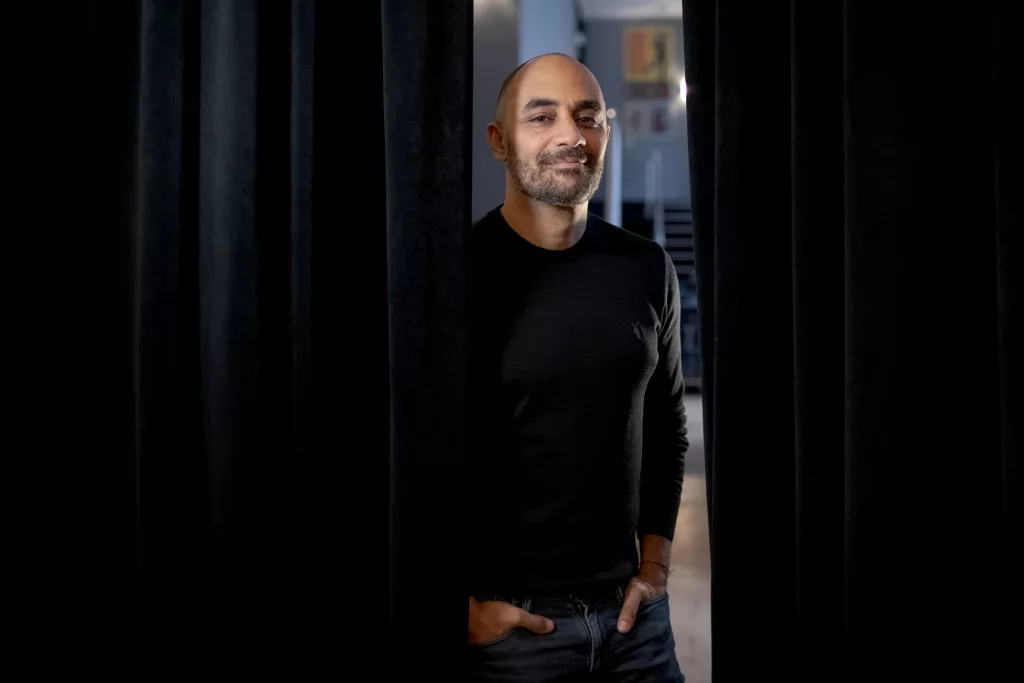

WHEN SAHEEM ALI was in high school, he read about the myth of Marimba, the goddess of music. She’s beautiful and talented and because everyone loves her, her mother places a curse on her — to never fall in love. Now 45 years old, Ali still remembers the story. As the Associate Artistic Director and Resident Director of New York’s Public Theater, he considers the story of Marimba his dream project if he had resources like one of his first loves: Shakespeare. Before he moved to the United States at age 20 from Nairobi, Kenya, in 1998, he acted in “Romeo and Juliet” in Kenya when he was 19 years old. Lupita Nyong’o was in that production, too. But when it came time to think about his career as a director, he decided he wanted to pursue musicals, and he told himself “Goddess” would be his first original Kenyan musical to appear on Broadway.

Ali has been developing “Goddess” over the years with playwright Jocelyn Bioh, but his most recent work is the musical “Buena Vista Social Club,” which concluded its theater run at the Atlantic Theater Company earlier this year in January. We had a conversation about his plays, including his Shakespeare in the Park production of “Merry Wives,” his Tony-nominated “Fat Ham,” and about living in New York City. Two things stood out to me in our conversation: Ali moved to the U.S., saw that people of color were excluded from playing central characters in Shakespearean plays, and he made it his mission to create productions that center people of color. He’s done so, and he’s done so successfully.

I was watching the documentary about producing “Merry Wives” on HBO, “Re-opening Night”. There was a scene where the playwright Jocelyn Bioh was climbing the stairs, I think, to your apartment.

That is the apartment I’m living in right now, yeah.

I was like no elevator? This is so New York. How many floors is the walk up?

It’s five floors up. Every day up and down, it is just the stairs. It’s nothing else.

And, you don’t intend to move?

No, I’m very happy where I am.

Stressing people out in your home.

My friends have to deal with it. They’re like “Oh my God, I have to climb.” Sometimes my friends are like, “Saheem, I love you. But today, you’re gonna meet me at the coffee shop. Because I’m not going to come up the stairs.”

Do you think of yourself as a Kenyan immigrant in the city, as a New Yorker, or both?

It’s really all of the above. I’ve now officially lived in the U.S. more than I lived in Kenya. I’ve been here for more than 25 years now. I lived 19 years in Kenya. So, that’s obviously a part of my identity that will always be at the foundation.

But New York is home now. My community is here. My profession is here. I know more about the politics of the city and country than I do about even politics back in Kenya because it doesn’t interact with or influence my day-to-day in quite the same way.

Can you tell us about your experience in the city? Where in the city do you feel more connected to?

I live in Midtown and work in the East Village at The Public Theater. I walk to work and back, up and down Broadway. I always dreamed of living in Manhattan and being able to walk to work, so that walk to me feels very much like New York.

“I always dreamed of living in Manhattan and being able to walk to work, so that walk to me feels very much like New York.”

A Kenyan friend of mine told me what’s interesting about being Kenyan in NYC is that Kenyans don’t have high immigration rates here. Do you perceive this to be true, and if so, what community do you have here as a Kenyan?

Most of my friends here are Ghanaian. I have a few Nigerian friends. There are fewer of just Africans in general in the theater community because it doesn’t tend to be a profession that is easy to get into from the outside. Actually, I came as a computer science and communications major. I planned on that being my path, then I took a detour in school. I was doing the arts as a hobby, but being here gave me the confidence to pursue my dream and decide to be an artist. It’s a lot more challenging for non-Americans to immigrate here for the arts because they tend to be in the service industry, technology, medicine, that sort of thing. Most of my friends were African American. My community was. Then suddenly I started to meet all these West Africans, and that really became my community.

Also Read: “The Wire” Actor Gbenga Akinnagbe Performs One-Man Stage Play on LGBTQ Asylum Seeker

What’s been the experience of staging a musical about the “Buena Vista Social Club,” compared to the other plays you have directed or worked on?

The big experiment with “Buena Vista Social Club” was can we create a musical where all the spoken words are in English but the songs remain in Spanish, and that you can still enjoy and follow the story even if you don’t speak Spanish? That’s a first. There’s never been a musical that has had those two languages completely side by side in that way, and it worked. The audiences loved it; whether or not they knew the album, whether or not they speak Spanish.

“Merry Wives” was set in New York City, how did you draw inspiration to direct it?

When it came to creating a production for Shakespeare in the Park, I knew this was going to be the first big production after COVID-19 isolation. So, I wanted to do something that celebrated New York City. I found that setting in Harlem, with West African immigrants.

In the original “Merry Wives,” there are different identities — British, Scottish, Irish — and they kind of make fun of each other because of their accents. I thought, well, I want to create a piece that uses “Merry Wives” the original, but all West African identities, and they are not making fun of each other’s dialects but there’s an embrace and a love for the differences.

Something I believe is Shakespeare doesn’t have to be all Shakespeare. You can do a Shakespeare play that has some contemporary texts. I just did a play called “Fat Ham” on Broadway. Again, I put people of color in the center; it’s an African American southern identity and they’re speaking Shakespeare’s words with that accent.

Is the intent of making a Black-centered Shakespeare play, representation for Black people i.e. for Black people to see themselves portrayed in a literary classic? Or is the intent corrective in a political way, that is to say historically, Black people haven’t played Shakespeare in the U.S., so let’s correct that, or is it both?

I would say it’s more of the latter. I’ve always loved Shakespeare. My first Shakespeare play was in Kenya, but coming to America, in my first early years, all the Shakespeare I saw had white people in it. Then, a lot of them were speaking in a British or American accent. I felt very removed from it because I didn’t see people who looked like me. It really became my mission to say no, we can have someone who is Andre Holland, who is a black American play Richard the second, play this great English king.

We’re not British, so why can’t it be a black person instead of a white person or a woman instead of a man? I just think we are at a point where we can interrogate those assumptions. There are so many incredible actors who I’ve known, who have never been given these great big parts.

We are in a tradition that is now just catching up with the breadth of storytelling and opportunities for Black actors and brown actors. People of color didn’t have the opportunity to write plays that would be published at the same rate that white artists did, so, while we are catching up, and until enough of those plays are written, if we’re going to resuscitate these old stories, there’s absolutely no reason why people of color can’t inhabit them.

We all have different things to care about, and I believe in doing work that I care about, that fulfills a certain ethos that’s important to me. That’s where it begins. “Merry Wives” could have happened, but it wouldn’t have happened in that way if it wasn’t for what I felt was important to me, as an immigrant here and the kinds of stories that I want to elevate.

“I’ve always loved Shakespeare. My first Shakespeare play was in Kenya, but coming to America, all the Shakespeare I saw had white people in it. It really became my mission to say no, we’re not British, so why can’t it be a black person instead of a white person or a woman instead of a man?”

That community that was depicted in the show [“Merry Wives”], they live just north of Central Park, and Shakespeare in the Park is in Central Park. Those are New Yorkers, who sound a certain way, who look a certain way, but that’s the beauty of New York. I maybe could not have done that show in Finland, you know. But that’s why I don’t live in Finland. That’s why I’m in New York. I want to see diversity when I walk down the street.

Do you think you’ve helped influence the perception of immigrants in New York and America at large through storytelling?

That I don’t know actually. I really try to take responsibility for the art and the art making. Then, I do my best with whoever is the producing entity to make sure there is access for the communities depicted on stage, so it’s not just siloed, and it’s not just a homogenous white American audience who are in the seats when really, I’m making this show for everyone.

There are all sorts of barriers to the experience of coming to the theater. It’s very expensive to go see a show, especially if it’s in one of the bigger theaters in New York. I think about that very much. Communication, advertising, making sure that we’re letting certain communities be aware of the shows, because it doesn’t matter if you make it for that community, if they don’t know where it is, or how to get there, or that it’s happening, or what time the shows are, then, it doesn’t mean anything.

What is your grandest ambition for a story that if you had the resources like Shakespeare had, for instance, that you’d want to become a classic?

That’s easy. That’s ‘Goddess’ for me. ‘Goddess’ is my baby, is my dream. To have an original Kenyan musical onstage in New York and running for many years like ‘Wicked’ and ‘Hamilton,’ and all those. That is my goal. That is my dream.

Are you able to share an estimated time you foresee that “Goddess” would start showing?

We’re hoping to be on Broadway next season. So hopefully, knock on wood, about a year from now.

Do you miss being on stage?

No. I really don’t. When I was acting, I couldn’t stop thinking about everything else. Like, why are the lights doing that? I was always editing and criticizing in my head.

This interview has been edited for concision and clarity.