Two years into a 33-year prison sentence for a murder he says he didn’t commit, Alvin McLean stared at the items before him: a pen, paper, a water bottle and slippers—the small comforts of modern living—and contemplated his life. Then just 28 years old, he hadn’t done much, he thought.

The revelation spurred him. Now 51, McLean has spent much of the last 24 years working from prison to help inmates like him, prisoners held until their eventual deportation. McLean is imprisoned at the maximum security Sullivan Correctional Facility in Fallsburg, N.Y., a small town in the Catskills. In five years, he will be eligible for parole. If granted, he will be immediately deported.

Across the U.S., at least 35,000 foreign born prisoners will likely be deported upon their release, according to the Department of Justice. Many, like McLean, have spent little if any time in their home countries, having come to the U.S. as children. In New York, there are few organized programs to help them adjust.

McLean arrived in Brooklyn from Jamaica with his family in 1972, when he was just five years old. As a teenager, he drifted into the Brooklyn “underworld,” he said.

In August 1987, an 18-year-old named Andrew Garrett was killed in a Queens apartment, according to court records. Police arrested McLean and four teenagers a few weeks later. Their stories diverged, but one witness testified against McLean in court and picked him out of a line-up, according to NYPD documents. McLean maintains his innocence.

Shortly after being arrested, McLean slipped out of Rikers Island and spent several years living on the run. He was eventually re-arrested in Miami. “I definitely have some Maroon blood in me,” he said, referring to the Africans who escaped from slavery in Jamaica and established communities in the mountains. “When you’re innocent, you have to escape.”

He was found guilty on several charges including murder and sentenced to 33 years to life. He has tried multiple times to get lawyers from a New York-based innocence project to take on his appeal, but has not succeeded.

Before his transfer to Sullivan, McLean was housed at Shawangunk Correctional Facility, a maximum security prison 86 miles from New York City. He worked at the transitional services office, helping prisoners get necessary documents to acclimate to life outside; birth certificates, drivers’ licenses and Social Security cards. He also held counseling sessions with younger, more volatile prisoners.

But McLean knew his future diverged from the young men he was helping. They would eventually return to homes in the U.S. When he is released, McLean will be sent to Jamaica, a country he barely knows. He will be one of roughly 1,000 Jamaicans deported each year among about the more than 200,000 people deported overall.

In prison, he met many people like him: immigrants who have little experience or knowledge of the countries where they will soon be sent to live. He had found that most people were unprepared for the trip back to their counties of origin.

Convicted deportees in Jamaica suffer from a stigma similar to what American ex-convicts face. That makes finding work particularly difficult, said Carmeta Albarus, a forensic social worker and executive director of Family Unification and Resettlement Initiative, a Harlem based non-profit that works with Jamaican deportees. McLean has volunteered with her organization for nearly a decade, writing grants, conducting research and producing educational materials, she said.

In the facilities where he was housed, non-profit organizations and publicly funded programs help ease the transition out of incarceration into society through job training, social support and connections to resources outside prison. McLean says that no programs designed to help prisoners prepare for deportation exist in New York State, so he decided to start his own. The state Department of Corrections and Community Supervision says it supplies transitional programs, including access to consular services, but McLean says there’s a need for specific deportation services.

In 2010 he gathered 25 immigrant prisoners in Shawangunk and held a counseling session on preparing to be deported.

McLean asked them to unpack the circumstances of their lives in their home countries. Did they know anyone there? Did they have any savings? Did they have any employable skills? Did they have idea of how to get a job?

Few deportees have a plan of what to do after they step off the plane or bus in their country of origin, McLean said. Some have been gone for decades and have no ties to the land. Others came to the U.S. recently and can slip back into their community, but face the stigma of being a deportee. Many have no home, no means to support themselves and no way to find a job.

“How can you get your feet off the ground?” he asked them. “A lot of guys have no interest in living there, only in coming back.”

In one session, several people attending the group belonged to Mara Salvatrucha 13, the El Salvadoran street gang, McLean recalled. They were apprehensive about returning home. They were fearful that the violence of their past would lead to police harassment and being cast from society, Mclean said. “The first thing you do when you get back is reach out to local police and anyone you harmed to tell them, ‘that’s not me anymore, that part of my life is over.’”

“A lot of them were trying to seek political asylum,” he said. They were worried about being targeted by other MS 13 members, he said. “They let that life go. Once you’re in [the gang] that’s it. If you come out, they’ll take you out. They’ll take you out by taking your life.” The last time he held a deportation counseling session was 2015.

Soon, McLean turned his attention outside the prison. Over phone calls and letters, he gathered information from the embassies and consulates of Central and South American countries.

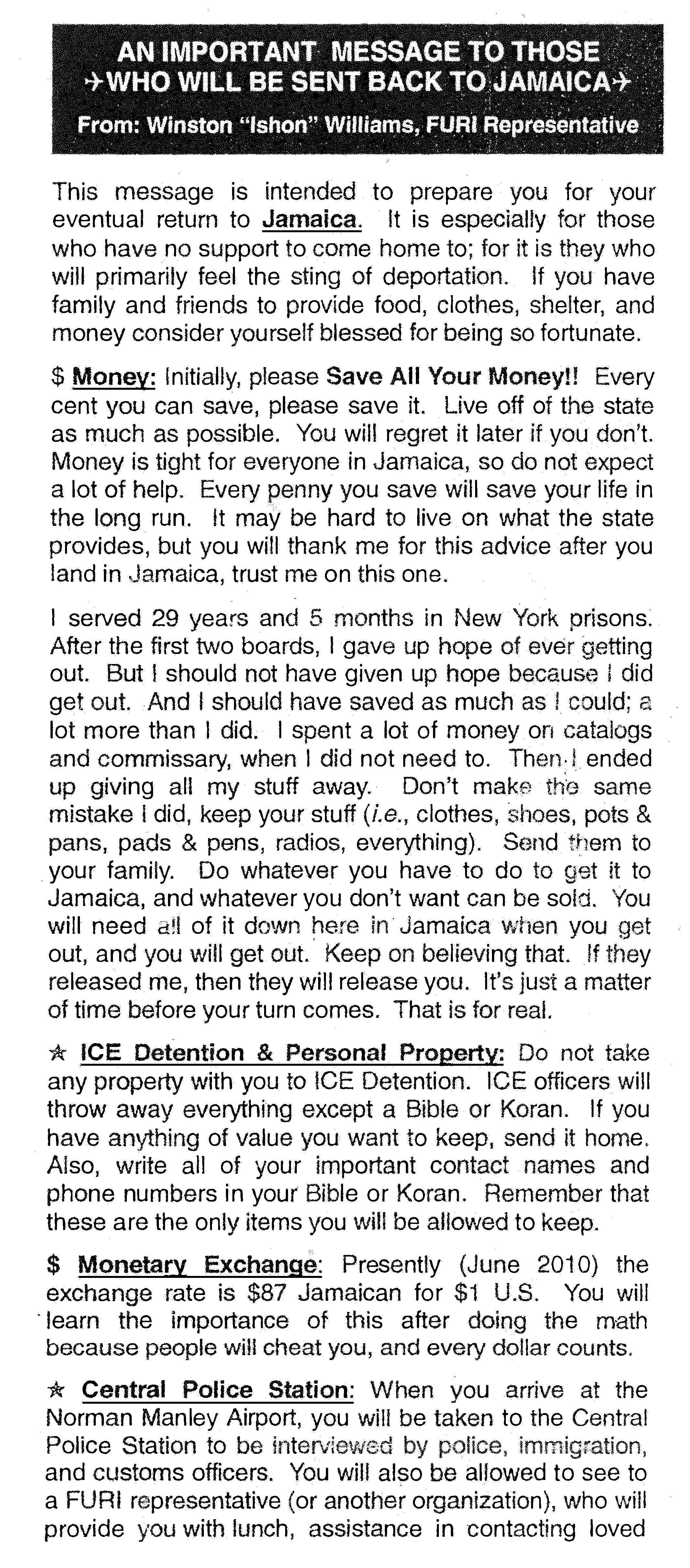

“Money is tight for everyone in Jamaica, so do not expect a lot of help,” Winston Williams, a former inmate who spent 23 years in prison before being deported to Jamaica, wrote in one of McLean’s publications.

He found a Mexican-born prisoner who could translate the information into idiomatic Spanish. McLean designed pamphlets and sent them across the country to nonprofits and embassies.

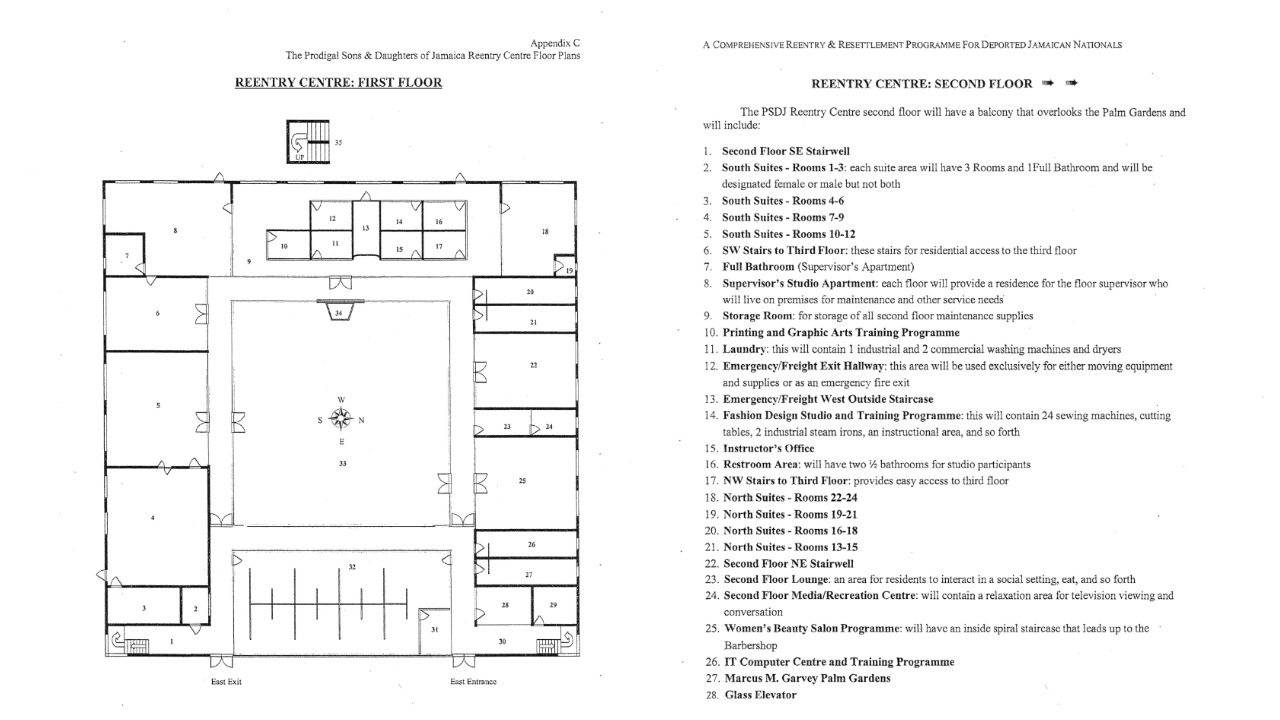

He corresponded with the reentry institute at John Jay College. He gathered statistics about deported Jamaicans and compiled them into a 136-page plan for the Jamaican government to address the issue of deported Jamaicans. It included a seven-page index and detailed blueprints for “The Prodigal Sons & Daughters of Jamaica Reentry Centre,” a building he designed to be built in Kingston for the recently deported.

The Jamaican government ignored most of the plan, but did allow deportees returning to the country to ship goods back to the country tax-free, according to correspondence McLean provided to Documented.

“Little steps,” McLean said.

Recently McLean wrote a manual for Jamaicans new to the United States with Albarus and immigration lawyer Joan Pinnock. The manual lays out the basic steps of how to live in the United States, from riding Amtrak trains to sending children to college, as well as which legal pitfalls some Jamaicans can fall into.

Mclean was transferred to Sullivan Correctional Facility last year after 18 years in Shawangunk. He works in the prison’s law library, helping inmates learn about their cases and file motions in court. He has continued to petition lawyers to take on his case.

Most of the people he counseled left prison and they never spoke again. Mclean once had a radio show at Vassar College. Occasionally he’d get a caller he knew from his counseling, sending word of arrival in Jamaica. “Most people just want to move on.”

When he gets out, he hopes to work in prison reform, reintegration and helping people to prepare getting deported.

He, for one, is prepared.