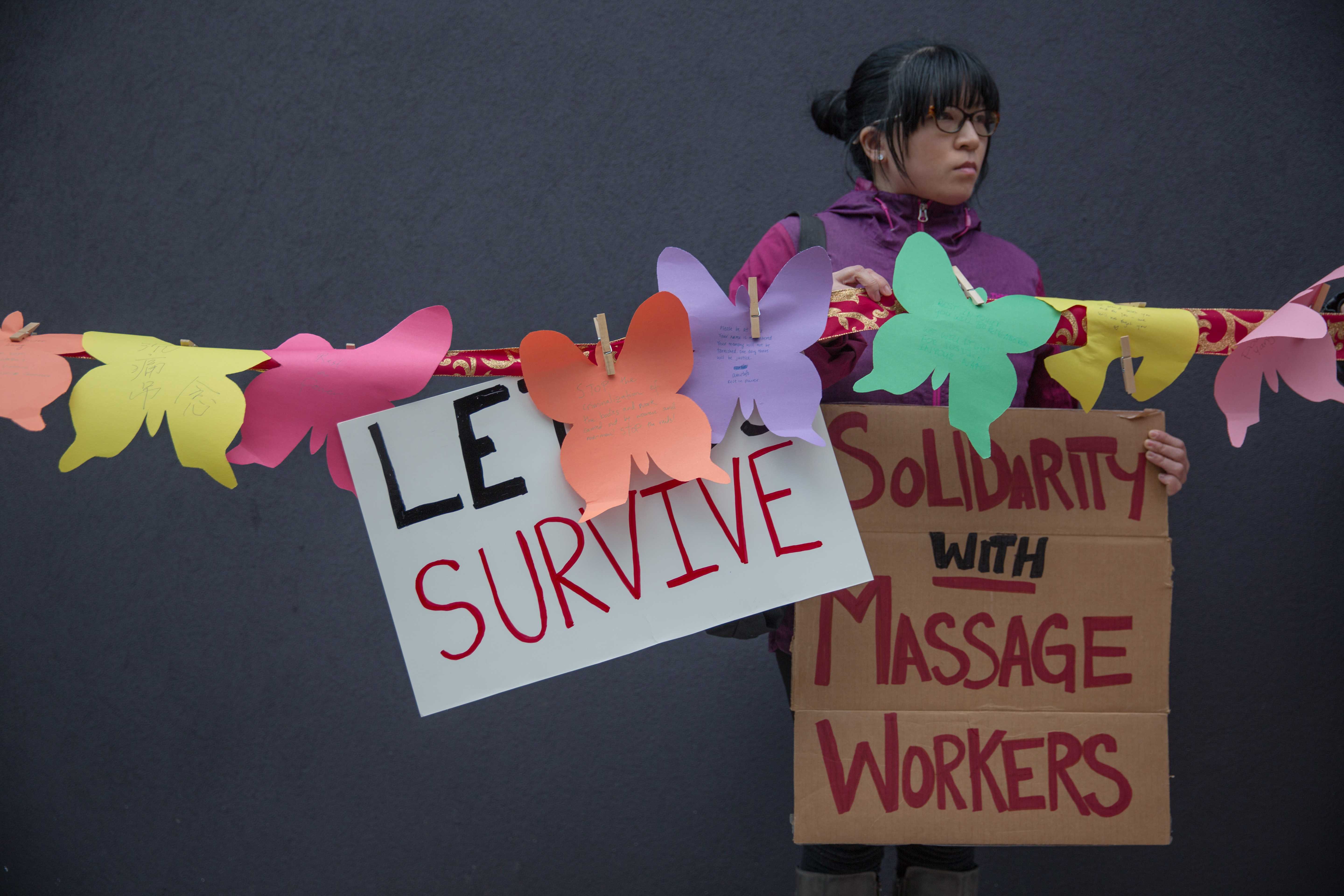

Exactly one year after she fell to her death during an NYPD vice raid in Flushing, Queens, dozens of sex workers and their allies joined the family of 38-year-old Yang Song on 40th Road, yesterday. Mourners held up a string of paper butterflies–which Yang Song’s brother, Hai Song, says she loved–and called for an end to massage establishment raids in both English and Mandarin, a few feet from the sidewalk where she landed.

“It is important for us today to be visible in our remembrance of Song Yang, because migrant sex workers like Song Yang have so long been made invisible,” said an organizer with Red Canary Song, a newly-formed coalition of migrant massage workers in Flushing and Chinatown, who goes by the name Kate Z. Sex workers are “forced to perform either victim or criminal,” she added. “To be pitied or punished and nothing in between. We are not allowed to speak for ourselves.”

The Queens District Attorney’s Office released a report in November confirming they’d found no police wrongdoing in Yang Song’s death (or Song Yang in Chinese name ordering). The raid was in response to a complaint alleging prostitution at 135-32 40th Road earlier that month. “There are no facts or evidence which suggest… any criminal conduct,” the report states. But on Sunday advocates for sex workers and immigrants condemned legal policing of vulnerable immigrant communities in Queens, and called for the decriminalization of sex work: a movement that has garnered national attention in the wake of new federal anti-trafficking legislation.

Yang Song moved from China to Flushing with her husband in 2013. She had a temporary green card, and dreamed of opening her own spa, but worked first as a waiter and then as a sex worker on 40th Road to support her family. Advocates say her struggles – including multiple arrests and an alleged assault at the hands of a client – reveal the inadequacy of anti-human trafficking strategies that rely on close collaboration with police and courts.

“The NYPD has the obligation to protect all of its residents,” Hai Song told Documented Sunday through a translator. However, “In the past when [Yang Song] was harassed or assaulted by others and went to the police for help, she never received it.”

In Queens, a specialized Human Trafficking Intervention Court diverts defendants charged with prostitution-related crimes to services, including counseling and healthcare. Yet public defenders say the experience of arrest and diversion can prove cyclical. When police attempted to arrest Yang Song on the night of November 25 last year, she was already facing a December 1 hearing for a prostitution-related arrest from September. The Queens DA did not respond to a request for comment at the time of publication.

Arrests of “Asian-identified” New Yorkers on charges of unlicensed massage and prostitution exploded in recent years according to a recent report from the Legal Aid Society and Urban Institute, from just 12 in 2012 to 336 in 2016. The NYPD pledged to arrest fewer people on prostitution charges last winter, as part of an initiative to focus their resources on arresting human traffickers and build trust with immigrants. The numbers have since declined. According to state data obtained by Documented, there were 39 unlicensed massage arrests of Asian New Yorkers between January and September of this year, and just 92 prostitution arrests.

“We’re seeing a significant decrease in [prostitution] arrests. That’s something we wanted to see,” said Dorchen Leidholdt, director for the Center for Battered Women’s Legal Services at the nonprofit Sanctuary for Families. Leidholdt’s group, which did not participate in Sunday’s action, is critical, but not dismissive, of the NYPD. “We need massive force-wide training on sexual exploitation,” Leidholdt said, adding that the increase in sex trafficking arrests this year – 41 as of September, according to state data, compared to 34 in all of 2017 – is “a wonderful thing.”

“The NYPD will continue our thorough investigations into illicit massage parlors because they are illegal and are a motor for the human trafficking trade,” said NYPD Lieutenant John Grimpel in a statement to Documented.

But many massage establishment workers in New York City are not trafficked, according to Mary Caparas of Womankind, a nonprofit that serves East Asian survivors of trafficking and domestic abuse in Queens. Instead, Caparas said, the majority of her massage establishment clients say this work is one of the only options for noncitizen Asian immigrant workers with limited English skills. “We’re trying to reduce the barriers for people who are trying to get their massage [therapy] licenses,” she explained. “Work that’s a lot more stable, [with] fair pay, and safer, too.” This includes offering English classes, and advocating for revisions to New York’s massage licensing requirements.

Meanwhile, even as prostitution-related arrests decline, Kate Z. says that workers are still fearful. A former sex worker herself, she co-founded a coalition called Red Canary Song in direct response to Yang Song’s death and is now planning know-your-rights trainings.

“These laws against human trafficking, which use criminal law and policing instead of labor rights and immigrant rights to remedy exploitation, only serve to create more violence,” she said Sunday, before mourners wound the string of paper butterflies around a signpost on 40th Road. “These laws… are literally killing us.”

This story was updated on Nov. 27, 2018 to include a comment from the NYPD.