The family stood outside the Roosevelt Hotel intake center in late October, surrounded by grocery bags and backpacks stuffed with their belongings. They held a map and directions to a new hotel they were told to go to. It would be the third shelter they would sleep in, since they arrived in New York about a month ago. Once again, they were on the move. A piece of paper held by the father instructed them to return to the Roosevelt Hotel on Thanksgiving day. Then, they would have to leave their new home, and once again return to the Roosevelt to ask for a new place to live.

The family — a husband, wife and daughter, Aranza — had arrived in New York several weeks into the school year, so their little girl, just 6-years-old at the time, had been absent since the beginning of the year. Now, she missed another week of school, when the family was shuffled from one shelter to the other.

“We didn’t have another choice,” said Aranza’s mother, 41-year-old Erica Garcia, who lamented her daughter being unable to attend school that week. “We didn’t think it would be like this.”

Children like Aranza are missing school because of city programs and policies that limit long term hotel stays. Thousands more families will soon be forced to move shelters or look for other places to live in the coming months, as notices sent to them cut their shelter stays to 60 days. Educators and advocates are concerned that the moves will seriously disrupt the schooling of migrant children.

“It is critical to create a stable environment for the kids,” said Jennifer Pringle, the director of the learners in temporary housing project at Advocates for Children, an organization focused on children’s access to education. “Not knowing where you’re going to go day to day, where you’re going to be — you can imagine, it’s going to be difficult for the kids to engage in learning with that hanging over your head.”

Also Read: “Please, Don’t Deport Me:” Unaccompanied Minors Struggle to Fight Their Cases in Immigration Court

Migrant families living in the city’s shelter system have begun receiving letters that they must vacate their current facilities and find a new place to live within 60 days. But even before these more recent notices were distributed, families like the Garcias have been living with strict 28-day limits on their hotel stays through a separate program called the Hotel Vouchering Program, which was first reported by City Limits, and is run by the city’s Department of of Housing Preservation & Development (HPD).

The program uses blocks of rooms at participating hotels throughout the city as they become available for 28 days. If there is no room at a Department of Homeless Services location, or a Humanitarian Emergency Response and Relief Center (HERRC), migrant families with children are placed in rooms through the Hotel Vouchering Program, according to HPD. The city has placed migrant families in 1,821 hotel rooms through the program since its inception in July, across Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx. As of the week of Nov. 6, 447 households were receiving shelter at 16 hotels as part of the program, according to HPD.

William Fowler, a press secretary for HPD, said in a statement that the city has “often” leaned on the hotel vouchering program to “ensure newly-arriving families have a roof over their heads.” The program, Fowler said, provides 28-day hotel stays to migrant families with children “as a last resort when there is no other viable option.”

“While it’s not our preferred solution, nor a permanent one, it is a key part of our daily struggle to help people at the scale at which they arrive,” Fowler said.

Advocates note that even missing a few weeks of school can be detrimental, especially for young children. Chronic absenteeism, which is measured as missing 10% or more of the school year (which is about three and a half to four weeks of school), is associated with various negative educational outcomes, Pringle said. “Those early years in school are really critical in terms of learning early literacy skills, learning how to read,” Pringle said, noting that many of the migrant children have already had gaps in their formal education.

For Aranza, moving shelters meant that she had to travel from a hotel in Queens, back to the Roosevelt in Midtown, where she slept for four days. Then in late October with her parents, she traveled from the Roosevelt Hotel to East Elmhurst, to her new hotel — which she would soon have to leave again in 28 days.

On top of potentially missing school days, the question remains if children will have to switch schools when they are moved to a different hotel shelter. But New York City Mayor Eric Adams has remained adamant that kids will continue to have stable schooling situations.

“I want to be very clear on this — no child will have their education interrupted,” Adams said at a press conference in October. About 30,000 migrant children have been enrolled in New York City public schools for the 2023-2024 school year, according to the city.

Pringle doesn’t buy the mayor’s assurances. “The mayor has said the kids can stay in their same school, but that’s an empty promise, if you have no idea where you’re going to be, how close you’ll be to that school,” she said. The situation caused by 60 day notices, Pringle said, “is a recipe for disrupting kids’ education.”

The New York City Department of Education (DOE) referred questions to City Hall.

“It feels like two steps back”

Aranza, who is in first grade, enjoys her current school, she said. But, “almost everyone speaks in English,” she said. Still, she was eager to show off some of what she had learned. “I already know up to one, two, three…” She counted carefully up to 10 in English, before switching into the alphabet, and saying the letters up to G.

Aranza was born in Venezuela, but her parents are Peruvian and had been living in Peru with her before coming to New York. The family has now been in New York for about two months after making the arduous journey through the Darién Gap, Central America and Mexico — and is now staying at a hotel near LaGuardia airport. For Aranza, the experience of regularly moving between facilities has been confusing, her mother said.

“It shocked her, because she was saying: ‘Why do we have to be going from one hotel to another?’” Garcia, Aranza’s mother, said. “She is basically not attending school for all the dates that she needs to.”

Garcia has had little luck finding assistance to connect the family with long-term housing, so that Aranza can attend school every day, she said. At the asylum seeker intake center at the Roosevelt Hotel, she “asked if they could give me something stable — more than anything for the girl, for the school, since I had already enrolled her,” Garcia said. “But they told me that I couldn’t ask for more, that I had to go where they sent me.”

In early October, another migrant family of three was standing on the sidewalk of the Roosevelt with their belongings scattered on the floor. That morning, the Venezuelan family had been forced to leave their hotel shelter in the Bronx after their 28-day stay at the facility had expired. At the time, more than a month into the school year, their 9-year-old daughter still had not yet been enrolled in classes because they didn’t have a reliable place to live.

The family didn’t receive much explanation at their Bronx hotel of what would happen next, Jenny said, except for instructions to return to the Roosevelt for intake. “They just sent us to [The Roosevelt], and that was it,” Jenny, who just shared her first name, said.

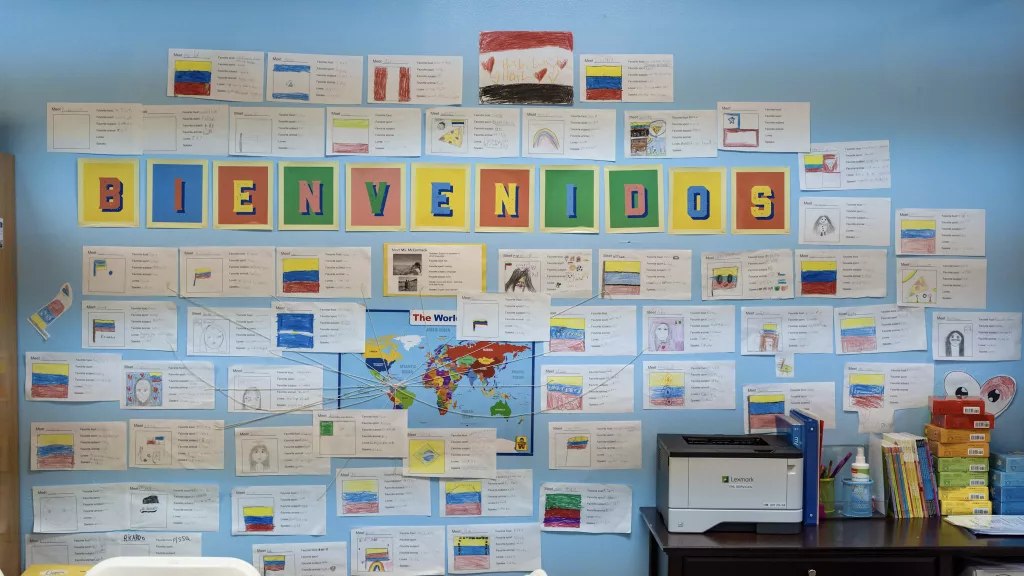

At VOICE charter school in Long Island City, about one third of the students enrolled are migrant children, according to school officials. Many are living in nearby hotel shelters, and have become close with the school community. But educators are apprehensive about what the children’s schooling may look like in the coming months as more 60 day notices are distributed and go into effect.

“When you break that natural cycle of the school year, it can be really traumatic,” said Franklin Headley, the principal and founder of VOICE Charter School. “The kids are feeling the progress, the families are feeling the progress, and then it feels like two steps back.”

Over the past year, the school has been working to adjust their infrastructure to reflect the background of new students and families, including implementing a text service that automatically translates into English and Spanish for the parents where they can communicate directly with teachers, hiring operations personnel and social worker therapy staff who speak Spanish, and adding English Language Learner teachers. They’ve expanded meals so that children can take a breakfast for themselves, and for another family member. They’re also building a laundry room so that families can come wash their clothes at the school.

“For a lot of kids, and these kids as well, they get everything from here,” said Karina Chalas, the director of operations for VOICE Charter School.

But recently, some families living in a hotel near VOICE began to receive letters notifying them that they would have to soon search for new housing, and leave their shelter within 60 days of getting the letter. The letters say that the households can no longer stay at the hotel as of January 2, 2024, and that until then, it is possible that the city could transfer them to other housing facilities within the city’s system.

The notices do not explicitly state that families may return to the Roosevelt hotel for intake, as City Hall has said they can do, which may leave families thinking they have no options when their time is up. And now, educators worry that the close relationship between the school and the families will be interrupted due to these city policies.

Most children crave routines, Headley said. But “if they’re feeling more anxious, if they’re not as comfortable, they don’t feel as safe,” he asked, “how can their brains be learning?”