Once the government soldiers began firing military-grade weapons into crowds of civilian protesters, May Sabe Phyu said she knew there was no choice but to flee Myanmar.

“In Myanmar nowhere is safe,” said Phyu, who is a prominent women’s rights activist in the Southeast Asian country. “The military can easily find you. If they arrested me, I could end up living in prison for long years.”

In April, without her husband, son, and two daughters, Phyu arrived in Ithaca, New York — 7,971 miles away.

Since the coup, at least 1,000 civilians, many of whom participated in peaceful protests, have been killed by the military as of August, according to the latest accounting from Reuters.

Now, Phyu is a part of a sprawling community of refugees, asylum seekers and dissidents who have settled in Ithaca, a town seemingly in the middle of nowhere in New York’s Southern Tier. Home to two universities nestled in New York’s scenic Finger Lakes region, the city has become an unlikely place of refuge for those fleeing dangerous situations from Myanmar to Afghanistan, Venezuela and Syria.

Well before the coup this past year, Phyu said she was sued in September 2012 for organizing an International Peace Day parade without seeking permission from local authorities. The whole trial process took 14 months. Ultimately, the case was dropped under the president’s amnesty order because it received a lot of scrutiny from the media and international community, Phyu said.

Despite the constant threat of law enforcement and the option to go into hiding at the time, Phyu continued much of the same work, but she always knew she could face far worse than a lawsuit.

Recently, Ithaca has become one of the major hubs in New York for refugee resettlement. On Dec. 3, the city welcomed 10 Afghan refugees fleeing the Taliban after the fundamentalist group captured Afghanistan amid the U.S. military withdrawal. In 2016, Ithaca had been approved to accept 50 refugees a year, according to the Ithaca Journal. New York State resettled 820 refugees during the 2020 fiscal year. The majority of refugees — 520 — were resettled in upstate New York.

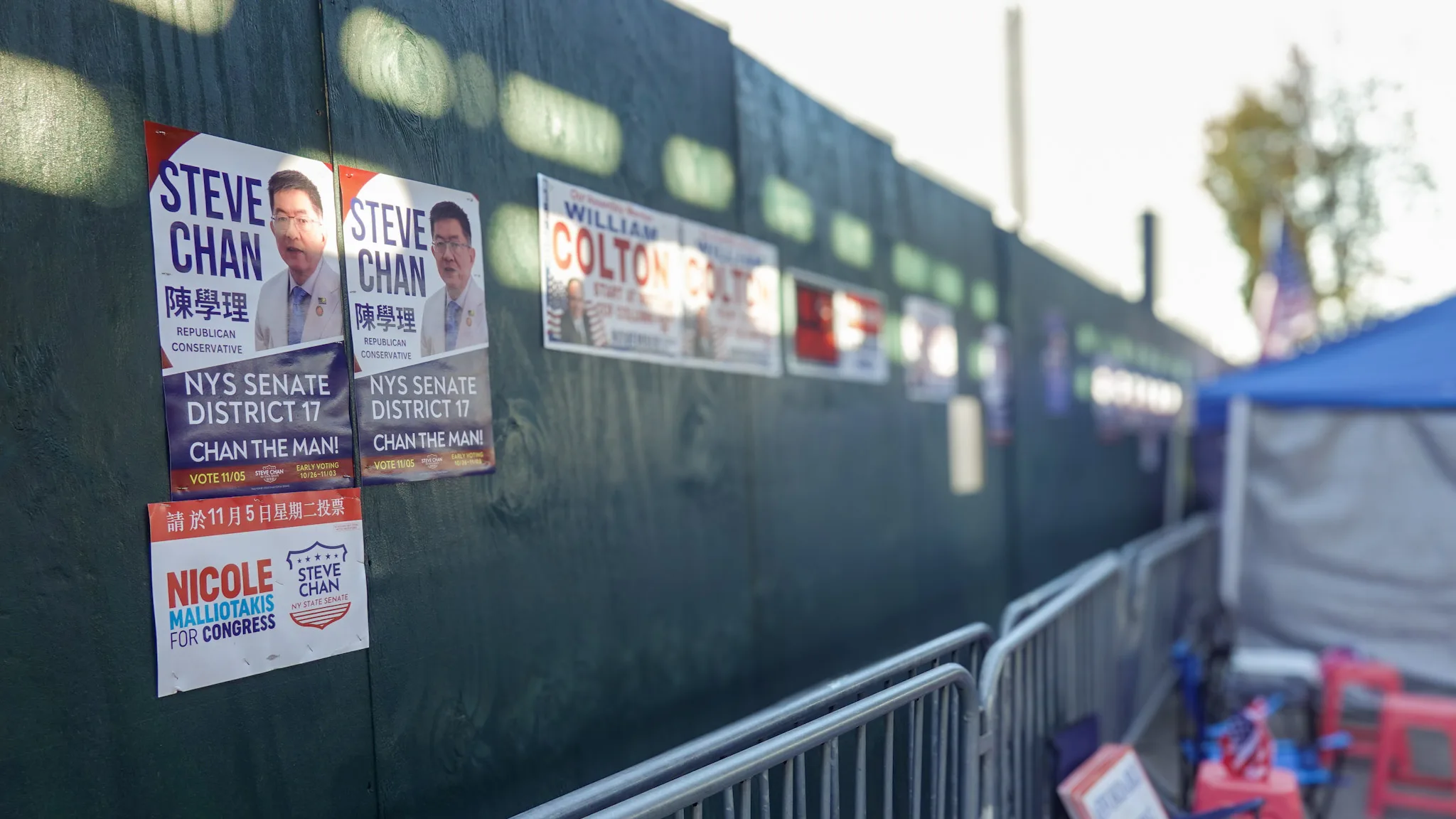

Ithaca — which is approximately 223 miles from New York City — seems like a strange place to completely start a new life. Looking like a time capsule of the 1980s with relics like the Center Ithaca food court and the many boxy, modernist apartments in the Collegetown neighborhood, Ithaca is a progressive city situated in one of the few red swaths of New York State; Ithaca’s congressional district, the 23rd, has consistently voted for Republicans since 2012. The district voted for former President Donald Trump in 2016 and 2020. Ithaca and Tompkins County, on the other hand, are liberal bubbles — in the 2020 election, it was the only county in its congressional district and one of few upstate New York counties to vote for President Joe Biden.

And Ithaca could hardly be a sharper contrast to Myanmar, a country of approximately 54 million people and home to 135 distinct ethnic groups. It has struggled with its democratic experiment, oscillating between military and ostensibly popularly elected government for decades. One landmark of progress came in 2015, when Aung Suu Kyi, a member of the National League for Democracy party, was elected Myanmar’s de facto civilian leader in what were widely considered the country’s fairest elections in decades.

But that progress came to a crashing halt in February of this year. After the NLD won the country’s second national election in a landslide in 2020, military rule came back to Myanmar, Suu Kyi was placed under house arrest, and the military then killed and imprisoned thousands protesting their return to power.

In September, Phyu’s family was able to join her in Ithaca, and they now live at an apartment complex, supported in part by her appointment at Cornell as a “Scholar at Risk.” Her Myanmar passport expired three months ago, she said, and she currently is navigating the process of seeking a more permanent residency in the U.S.

Still, while Ithaca may be cold, expensive and remote, for so many refugees, like Phyu and her family, Ithaca is home.

“Since we have experienced a lot of stress and trauma,” Phyu said, “it is a place that could heal.”

The First Refugees Arrive

Some of the earliest available records of a “foreigner” arriving in Ithaca date back to 1849, when a Chinese man was “on display” in town, according to an Ithaca Chronicle article.

Ithaca soon started to see more Chinese people settle in the area in the mid 1800s, according to Tompkins County Historical Center Archives. The first Chinese residents of Tompkins County were John and Mahjong Lee, who operated a Chinese laundromat on North Aurora Street in 1886, according to archives. Two years later, another Chinese family settled down in Ithaca and operated a laundromat on the same street. An Ithaca Journal writer, with overt racism, suggested that the stretch of Chinese laundromats on North Aurora Street be named “Washee Washee Lane.”

John and Mahjong Lee were in Ithaca only less than a decade after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred further Chinese immigration to the United States in 1882. The racist and xenophobic legislation passed out of unfounded fears that Chinese immigrants were taking up too many jobs while depressing wages. The Chinese Exclusion Act was the first time the U.S. barred a specific group from entering the country; the act wasn’t repealed until 1943.

But well over a century later, Ithaca began to welcome a deluge of refugees and migrants from Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos in the wake of the Vietnam War, extending a welcome to countries toppled due to widening Cold-War era conflict.

In 1975, Vietnamese migrants, referred to in local news clippings as the “boat people,” arrived in Ithaca in what was perhaps the first major migration the relatively small college town had experienced in decades. It wasn’t a “migration” that only concerned college students living in Ithaca for a short four years; this time, it was people escaping the horrors of war looking to establish a new way of life for themselves. Dewitt Historical Society records show that as of 1983, there were roughly 100 Vietnamese migrants in Tompkins County. Many of the first Vietnamese refugees that settled in Ithaca were there only temporarily; they soon moved to bigger cities and places with warmer weather, according to a 1983 Dewitt Historical Society newsletter.

But one of the most significant migrations in Ithaca’s history occurred in 1991, when the U.S. government authorized the arrival of 1,000 Tibetan refugees, and listed Ithaca as one of 10 “cluster sites” to resettle the Tibetans; the upstate New York collegetown was slated to take in 50 Tibetan refugees a year. Other sites included New York City, San Francisco, Madison, Wisc. and Amherst, Mass.

The following year, a group of Tibetan monks traveled from Dharamshala, India to Ithaca to establish a branch of the Namgyal Monastery, which became the North American seat for the Dalai Lama. The monastery is currently building a library to house the works of the current and previous Dalai Lamas.

Even today, the presence of these refugee communities can be felt in Ithaca. From the Tibetan Momo Bar on East State Street to the Cambodian food stand that’s become a mainstay at the Ithaca Farmers Market, these communities have become a part of the fabric that makes Ithaca, Ithaca.

And the tradition continues.

A Cartoonist Flees a Government Crackdown

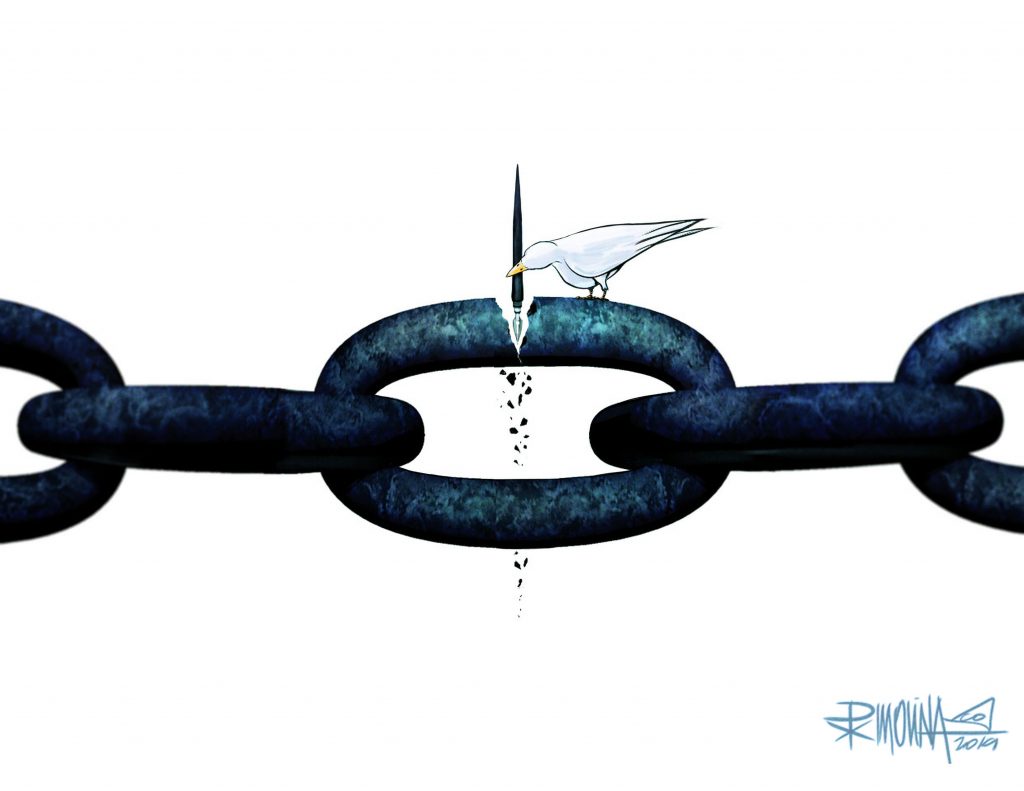

Pedro Molina, an editorial cartoonist from Nicaragua, set out for Ithaca in December 2018, after Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega’s government began to actively hunt down and arrest independent journalists.

“It became impossible to keep doing [journalism] from inside the country,” Molina said.

In 2018, amid mass protests against Ortega’s administration and social security reforms, the Nicaraguan government started raiding media offices, trying to stymie their coverage of the opposition. Journalists would be arrested for “inciting hate.”

Nicaraguan authorities raided the office of Confidencial, the publication where Molina works. He said they seized the computers and other equipment in the office. While Confidencial staffers were able to receive donated computers and other equipment to continue working, Nicaraguan authorities soon raided the office and stole the equipment again.

Then, the authorities ransacked the office of a television news channel. While no one was present in the Confidencial office when authorities stole its equipment, there were two journalists working in the news channel’s office at the time police barged into the office. Those two journalists were subsequently arrested and charged with terrorism.

So, in December 2018, Molina and about 100 other Nicaraguan journalists fled Nicaragua, scattering themselves across the globe, he said. Molina initially intended to go to Mexico, but once he received an invitation from Ithaca City of Asylum to take up residence in Ithaca, he knew he couldn’t say no.

“In a matter of two or three days, I changed my destination,” Molina said.

But this isn’t the first time Molina has lived in exile. When he was 10 years old, he said he and his family had to flee Nicaragua due the ongoing civil war in the 1980s.

While Phyu was able to come to Ithaca through Cornell, there is a patchwork of other organizations in the city that also help resettle refugees. Ithaca City of Asylum, or ICOA — which worked on Molina’s case — is one. Specifically, the organization works to take in writers and artists from countries where their works are censored and where their lives are endangered.

Since 2001, ICOA has hosted poets, writers and journalists from China, Pakistan, Iran and Swaziland, providing them a two-year residency in Ithaca, with financial assistance to meet daily expenses. The organization also subsidizes legal costs, Guaspari said. Once that two-year residency ends, Guaspari said the organization tries to help its members figure out a plan to either stay in the United States, or find a new country to live in.

Molina said ICOA was the only organization willing to resettle his wife and two young children as well. He received offers from other international assistance programs, but none of them could accommodate his family. ICOA helped Molina’s children get settled into local schools and arranged English lessons for his wife.

Molina, who remains working for Confidencial, though remotely from Ithaca, said he’s fortunate to be here because he still has the opportunity to work as a cartoonist, even if in the confines of his Ithaca apartment.

“I went to visit some colleagues who also left Nicaragua and are living in Miami,” Molina said. “I went to visit some of them down there. And some of them are painting houses or doing other kinds of jobs to sustain themselves. And, when I went there to talk to them, and see how they were doing, it was like, ‘Oh my God, I can’t even complain.’”

Ithaca Welcomes Refugees

The quite literally named Ithaca Welcomes Refugees, or IWR, was founded in 2015 in response to the Syrian refugee crisis. More recently, the organization had been assisting with efforts to help Afghan refugees resettle in Ithaca, after the Taliban seized control of Afghanistan in August. Since its founding, IWR has also worked to resettle refugees from Myanmar, Colombia, Nicaragua, and in earlier time periods, Afghanistan as well.

Unlike ICOA, IWR doesn’t have a well-established relationship with Cornell or Ithaca College. Rather than helping refugees obtain teaching jobs at the two universities, IWR offers assistance with housing and childcare at the Global Roots Play School.

When refugees first arrive in Ithaca, they typically come through a refugee resettlement agency, which offers them assistance for 90 days. After that 90-day period ends, IWR typically helps with longer-term assimilation, said Casey Verderosa, the executive director of IWR.

But many of these organizations that help bridge the gaps have gone “dormant” along with the larger refugee resettlement agencies designated by the federal government, according to Verderosa.

The main refugee resettlement agency in Ithaca was Catholic Charities of Tompkins, however, the organization severed its refugee resettlement operations in 2017, after former President Donald Trump signed an executive order in January 2017 temporarily halting refugee admissions. The Trump administration proceeded to slash the number of refugee admissions to a historic low of 15,000. President Joe Biden raised the quota to 62,500 in May after facing backlash for maintaining the Trump quota.

As Catholic Charities of Tompkins lost its refugee resettlement agency status, Verderosa said IWR had been facing a lull, caused by combination of the low refugee quota and COVID-19.

Molina, the Nicaraguan cartoonist, said he is considering staying in Ithaca in the long-term because the community has been so welcoming. However, staying in Ithaca could potentially — and permanently — would require Molina to give up his job at Confidencial and find full-time employment in the area.

“It’s a very welcoming place for me and my family,” Molina said. “So, we are very pleased to be here. But for how long are we going to be able to be here? That I don’t know for sure.”