For Miguel Almonte, the problems started almost as soon as he walked through the door.

He already had significant medical issues by the time he was detained at Hudson County Correctional Facility in Kearny, N.J. in March of 2015. According to medical records viewed by Documented, he had already had multiple surgeries – one to remove a clot from his brain – and was suffering from carpal tunnel and chronic back injuries. He’d been on disability since 2012.

Shortly after he was detained, he complained to the staff about a shooting pain in his side, a sensation he likened to “somebody stabbing you.” Prison records reviewed by Documented showed that he had brought his concerns to the staff multiple times, only to be waved off. In one instance, he apparently had a scheduled clinical visit at the same time as a hearing in immigration court. When he got back from court, he found out his appointment was cancelled and was told he would have to reschedule it for weeks or months in the future.

Almonte was detained after an application for naturalization surfaced a misdemeanor drug related criminal conviction from 2001, fourteen years prior. Almonte said Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents came to his door and told him they were looking for someone else before entering and arresting him; a tactic they’ve been known to use.

The agents said they only needed to interview him and would let him go after it was over. He left his medication at home, figuring he’d be back that day. He called his elderly mother, with whom he lives, from the Department of Homeland Security facility at 26 Federal Plaza.

“They came and picked me up, they said I’m going to be out in ten, twenty minutes,” Almonte told his mother. “Ten, twenty minutes? It would be eight months.”

Almonte technically never actually lost his green card, but that didn’t stop him from almost dying in ICE detention. He’d held the legal resident status since 1987, when he arrived in the United States from the Dominican Republic with his grandfather.

ICE calls the facilities where they hold detained immigrants ‘detention centers,’ but they are often indistinguishable from prisons. In many cases, they are actual county jails, which have entered into agreements with ICE to house detainees accused of civil immigration violations. That is the case with the Hudson County Correctional facility, where Almonte was held, a jail with a checkered history of inmate death and abuse, including of immigrant detainees.

As his lawyer, Conor Gleason of the Bronx Defenders, fought to have Almonte’s immigration case dismissed, he also began to seriously worry about his client’s health. He filed documents with ICE asking for Almonte’s release on humanitarian grounds.

“They knew. I had the humanitarian parole request pending for months, and it was denied… I was told that they knew he needed surgery,” Gleason said.

Hudson county correctional facility and ICE’s New York and New Jersey field offices did not return requests for comment on Almonte’s detention and the denial of his humanitarian parole request by press time

Once, Almonte was taken to see a doctor at a different jail and the doctor never showed. Another time, he said he was injected with powerful analgesics and put into solitary confinement after loudly complaining of his searing pain.

A member of the jail’s staff told Almonte he had already “seen the doctor yesterday,” in response to one of his medical requests. Eventually, the medical staff discovered that he suffered from gallstones.

“You think they help people in there? Nothing. People have to help themselves,” Almonte said.

When the gallstones began affecting his ability to digest food. He had to start buying dry packaged goods and canned foods at the commissary at exorbitant prices. He couldn’t keep the regular food down. “Everybody knew what’s going on with me in there, because they see me always go white,” he said. “One corrections officer told me ‘you’ve gotta be careful, I’ve seen people pass away.”

Ultimately, Almonte was able to secure his release after borrowing money to post a $7,000 bond after a bond hearing at the six-month mark of his detention.

A late-2015 Second Circuit court decision, Lora v. Shanahan, had ordered that all detained immigrants in its jurisdiction – which included Almonte – receive a hearing after six months.

The future of that order remains in doubt after the Supreme Court ruled in February of this year that the Constitution does not guarantee periodic bond hearings for immigrants.

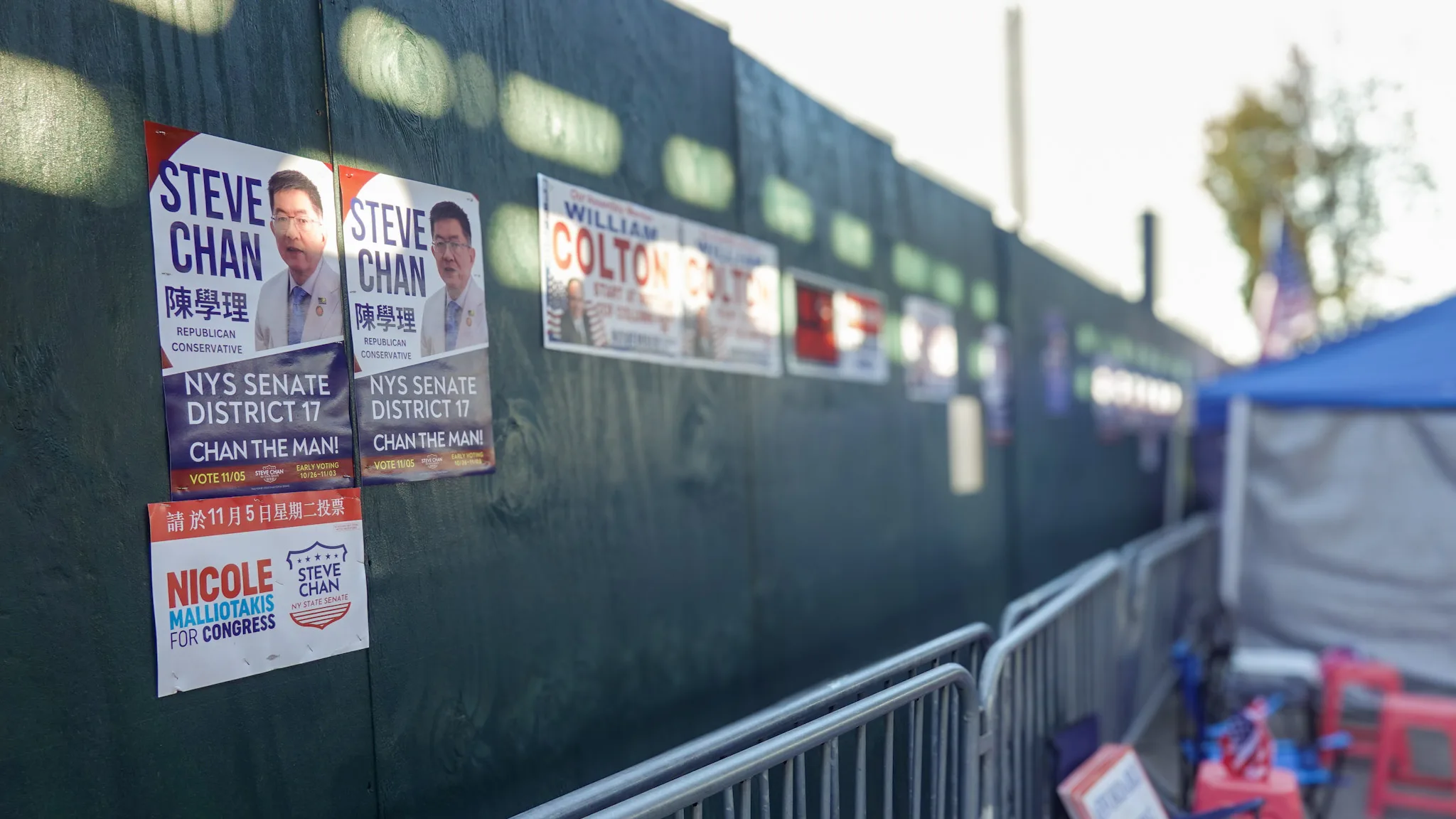

陈学理胜选凸显华人社区“右转”

After his release, Almonte had emergency surgery to remove his gallstones. “The doctor said ‘You’re lucky you’re alive. If you would have stayed a little longer there, I don’t know what would have happened,” he recalled.

As he was recovering, his mother had her own surgery, which she had been postponing until her son was available to take her. About a year and a half after he was released from the detention, an immigration judge granted him relief based on the determination that he had received inadequate legal representation during his criminal case over a decade prior. He’s now on his way to gaining citizenship.

Looking back, Almonte is disillusioned by his experience, especially now that the Supreme Court has decided that bond hearings for detained immigrants are not constitutionally mandated.

“What I lived there, I wouldn’t want anyone else, be it tomorrow, be it today, to go through what I went through. That’s something I don’t wish upon my worst enemy,” he said.