Contributing reporting by Amir Khafagy

The man introduces himself to recently arrived asylum seekers as Pastor Darwin. His business card says he is Darwin Maradiaga, the chairman and founder of a group he calls Family Vision, an organization that works with asylum seeker families navigating their new lives in New York.

At the Family Vision office in the Mott Haven section of the Bronx, dozens of asylum seekers spend their days waiting for that help. Wearing a black blazer and dress pants, the man assures them he’ll give them free food and clothes, assist them with their asylum cases, and provide them with job opportunities. He’ll even give them free tablets, he says.

But, others know him by another name: Adonis Giron.

In 2010, he was sentenced to up to ten years in prison for sexually assaulting a 12-year-old girl, according to New Jersey court records and local news reports. He was charged with molesting two other girls, who were 13 years old, but those charges were dropped after he pleaded guilty to the sexual assault charge, Steven Dill, the Hudson County Assistant Prosecutor at the time, said in 2010. Giron pretended to be an MTV talent scout and reached out to girls saying he could help them become models, Dill explained, according to The Jersey Journal. Giron, who was 42 years old at the time of the assault, served about seven years and four months in prison and was released in September of 2017, according to New Jersey Department of Corrections records.

Giron also pleaded guilty to two counts of third-degree theft by deception for posing as a representative of Western Union and the New Jersey State Lottery Commission, through which he obtained more than $38,000. He was sentenced in 2009 to probation, according to court records.

Documented spoke with Giron after seeing him leave the building listed as his address on the New Jersey sex offender registry. In an interview, Giron acknowledged that he had a conviction for sexually assaulting a minor. He told Documented that he was a changed man looking to make amends for his past, and emphasized that he has already paid his debt to society.

“I made bad choices in my life,” he said. “I feel sorry for the people I hurt. I feel very sorry, and I will never do it again.” He said he is trying to help asylum seekers build a future here and insisted that he never lied about who he was. He also said that his full name is actually “Adonis Darwin Giron Maradiaga.”

Still, Giron made sure asylum seekers knew him only by the title “Pastor,” “Pastor Darwin,” or by the name “Darwin Maradiaga,” though he declined to provide any identification with that name to Documented. In some online New Jersey court documents related to his convictions, he is referred to as Adonis D. Giron, but neither “Darwin” nor “Maradiaga” appears with his name. He could not provide evidence that he is actually a pastor.

Asylum seekers coming to Giron, who is now 57 years old, for help, said that he promised opportunities he couldn’t deliver on, like employment and free tablets, and took pictures or copies of much of their personal information.

On a recent visit to his Bronx office, Documented witnessed numerous children sitting with their families waiting to speak to Giron. He greeted the asylum seekers warmly and sat across from children as he met with their parents. Minors present at his office ranged from young children in strollers, to teenagers.

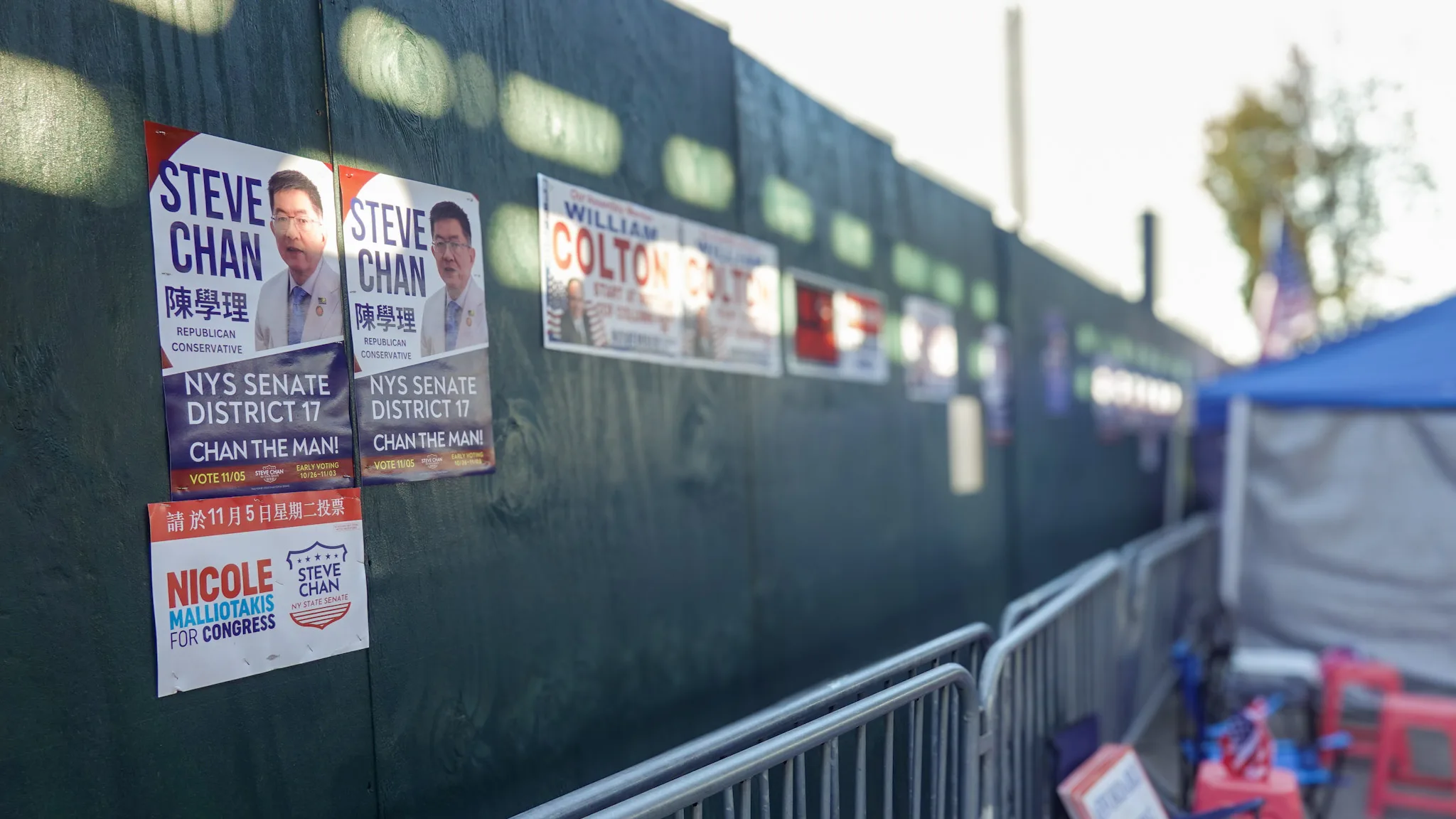

His phone number and the name of Family Vision have spread across communities of asylum seekers in New York City shelters. Some said they were even given his information at shelters in Texas. In January, Giron appeared with advocates and elected officials at a City Hall press conference about asylum seekers, according to a transcript of the news conference.

Asylum seekers who sought support from Giron in the Bronx said that they didn’t know he was a convicted child sex offender.

Reinimar Berríos Aldana, a 28-year-old mother of two from Venezuela who visited Family Vision twice with her children at the beginning of August, was shocked to find out about Giron’s past conviction. Berríos Aldana is alone with her two children in New York and brought her five-year-old daughter and ten-year-old son to Giron’s office with her to see if she could get help there.

“If I would have known,” Berríos Aldana said, “I would not have gone there, exposing my children.”

Giron said that all of the team members working at Family Vision are aware of his past conviction. Still, he said he does not specifically notify parents of children who come to his office about it. “I don’t have to tell everybody about my past,” he said.

Giron is under parole supervision for life under the New Jersey State Parole Board, said Patrick Lombardi, a spokesperson for the agency. The Office of the New York State Attorney General is aware of the situation and is looking into it, a spokesperson for the office said.

Giron told Documented that he went through about eight years of therapy and has built a strong support network. He said that he wanted to make a difference in the community through this group by aiding asylum seekers. “That’s the chance that I’m looking for,” Giron said. “To be productive in the community and never do bad things again.”

“Are we ready to start working tomorrow?”

Asylum seekers like Alberto noticed red flags soon after meeting Giron.

Alberto, a Venezuelan asylum seeker, arrived in New York with his son and wife in July. He had no social security number or employment authorization, but Giron immediately told Alberto, 43, that he could get him a job.

Giron was looking for a group of about ten workers, said Alberto, who shared only his middle name due to concerns about how the situation could affect his legal status. Giron helped organize a training session which Alberto attended in the building of the Family Vision office. There, a woman gave the group – all appearing to be recently arrived asylum seekers – instructions on how to sell tablets and phones in “strategic” places.

Giron told the asylum seekers the devices could be sold for $20 and up to $150 and told them to take a photo of the buyer’s ID and social security number. Several other asylum seekers said Giron told them they could sell the tablets he was going to give them. At that point, Alberto decided: “I’m not coming here anymore.”

Documented spoke with more than ten asylum seekers who have visited Family Vision. Some estimated that Giron has made contact with hundreds of migrant families who seek out his help.

Also Read: Eddy Alexandre Promised a Generation of Millionaires

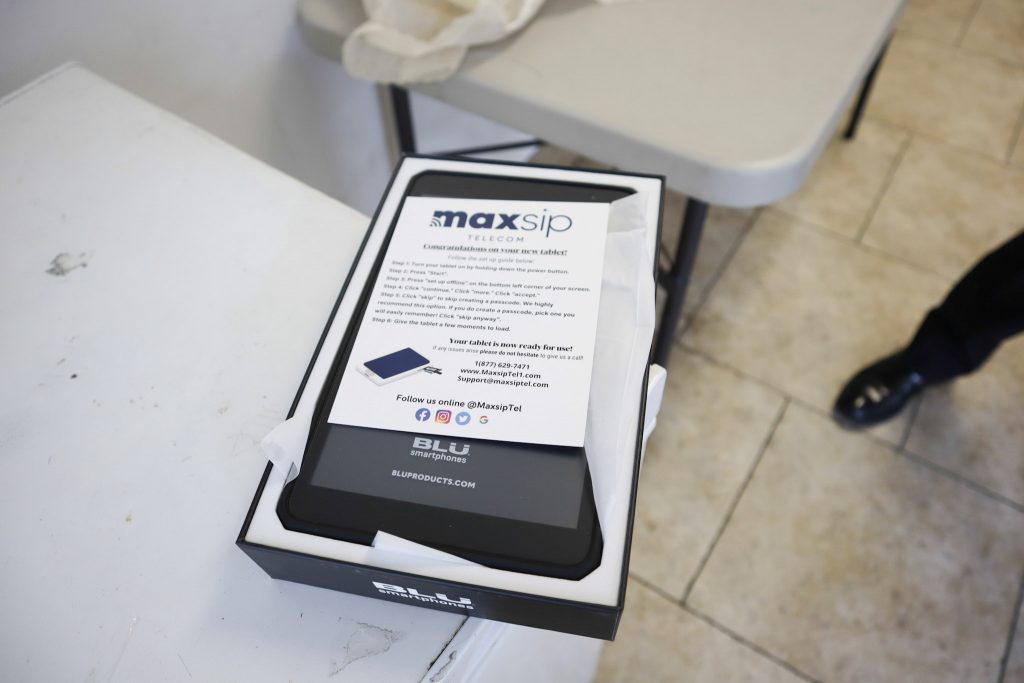

Giron told Documented that he gives out free tablets to asylum seekers in order to help them, but denied saying they should sell them. The tablets are from the telecommunications company Maxsip and are part of the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP), a federal government program run by the Federal Communications Commission. It allows some households to receive discounted internet and devices if they meet certain eligibility requirements, through Medicaid, SNAP, or other government assistance. Maxsip, the telecom firm that Giron said gives his group the tablets to distribute, is a provider of the ACP program.

The CEO of Maxsip, Israel Max, told Documented in an interview that in order to sell any Maxsip devices, a seller needs to meet certain requirements through the federal government – including having a social security number. “While the migrants are here, they are unable to sell for us because they don’t have social security numbers,” Max said. “They need to qualify through the government’s program system.”

Still, at the end of July, Giron added several people, including Alberto, to a WhatsApp group chat. In early August, Giron texted the group chat in Spanish to hurry up and arrive at the “foundation” because “the trainer is arriving now,” according to the messages. On a recent Monday, Giron texted the group again and asked: “Are we ready to start working tomorrow? Let me know.”

Asylum seekers said Giron promised them tablets they never received

Through the ACP, households can receive free internet service and a 4G Android tablet for a one time fee of $20, Maxsip says. But several asylum seekers told Documented that they never received the tablets they were promised, even though Giron took pictures or copies of their documents and the documents of their family members, which he said he needed to activate the devices.

Genesis Duque, an asylum seeker from Venezuela said that when she visited Giron’s office in the Bronx in early July, she accepted his offer of a free tablet. Giron photographed her and her husband’s identification cards, her immigration paperwork, her health insurance documents, and her children’s birth certificates, Duque said. Giron told her he needed her health insurance information to activate the tablet but Duque said he did not explain why he photographed the rest of the documents. Giron has still not given her a tablet. “I’m going to give you a tablet, I’ll give you a job,” Duque, 26, recalls Giron telling her. “He told me, ‘Everything that you need, I’ll give it to you.'”

Giron said he lost contact with Duque and that her device took some time to activate.

Giron was vetted by the federal government to sell Maxsip tablets, but he stopped working as a seller for the telecom firm more than two weeks ago, the company said. Giron has never made an official sale for a Maxsip device and was only ever given five Maxsip devices, according to Maxsip. “The devices he may have belong to the company, and he needs to return them,” Max, the CEO, said.

Documented spoke with six asylum seekers who let Giron photograph or make copies of their documents. Now, they are concerned about what exactly Giron is doing with the information on their personal paperwork.

“He has all of my information,” said Crisbey Martinez, a 23-year old asylum seeker from Venezuela with three children who first visited Giron with Duque on August 4. She says Giron took pictures of her immigration paperwork, the birth certificates of her children, and her husband’s identification. “He said: ‘Give me your documents, and I’m going to give all of you tablets, and I’ll give you all clothes and food.’ ”

Some asylum seekers are worried about how the situation could affect their immigration cases, too. “The day that I go to immigration court, I don’t know what problems I’ll be confronted with, that this man got me involved in,” Duque said.

Giron said he takes photos of documents from asylum seekers, including their healthcare paperwork, IDs and children’s birth certificates and inputs it into the Maxsip system so that they can be verified, he said. Giron told Documented that he never took pictures of asylum seekers’ immigration paperwork. “One can’t take pictures of immigration paperwork because it’s illegal,” Giron said.

Also Read: Immigration Attorney Leaves Numerous Undocumented Immigrants Exposed to ICE

Max, the CEO of Maxsip, said that a seller who has a vetted ID for the program from the federal government is allowed to input information into a device in order to activate it. However, on August 4, at the time that Duque and Martinez say they visited Giron’s office, Giron was no longer affiliated with Maxsip and would not have been allowed to input the personal information into the system, Max said.

Some asylum seekers at the Family Vision office told Documented — while Giron was in the room — that they appreciated Giron’s help and that he guided them through various matters, including providing assistance with shelter intake and immigration paperwork.

“Playing with our needs”

Giron has been inserting himself into migrant communities since at least last summer. He was interviewed by the local ABC7 news station last September about conditions in city shelters, and his group was featured on Spectrum News NY1 a year ago in a story about advocates providing resources to asylum seekers. In the Bronx, local restaurant owner and chef of La Morada, Natalia Mendez, said she has seen asylum seekers coming to La Morada from Giron’s office asking for food for more than six months. Sometimes more than 100 people arrive in one day, she said.

Ariadna Phillips, of South Bronx Mutual Aid, said her group has heard from dozens of asylum seekers who have shared various complaints about Giron over the past months. After finding out about Giron’s conviction, Phillips told Documented that he had “absolutely no business near any families – let alone newly arriving ones to New York.”

Giron acknowledged to Documented that he sincerely regrets what he calls the “mistakes” that he committed related to his sexual assault conviction.

Asylum seekers who have recently arrived in New York in the past month and went to Giron for aid said they got to the city with little more than the clothes they were wearing and a few key documents they had brought with them on the journey. Every day, mothers and fathers walked the streets of the city in multiple boroughs asking for a meal or a job where they could make a few dollars. So, they came to Giron, who they say sometimes provided some food, clothes and basic help. But, they were roped into questionable activities placing their future in the United States into question. Some said they felt Giron was severely taking advantage of their situations. Giron maintains that he is only doing good.

“That’s playing with our needs,” said Martinez. “We thought he was going to help.”

This story was updated with comment from the New Jersey State Parole Board.