It is becoming an axiom of political punditry that the Democratic Party takes its African-American voters for granted. Among progressive groups in New York, that maxim extends to the ballooning Latino population on Long Island, a potential political bludgeon that they believe has been ignored by the political establishment, but which could swing races if properly motivated.

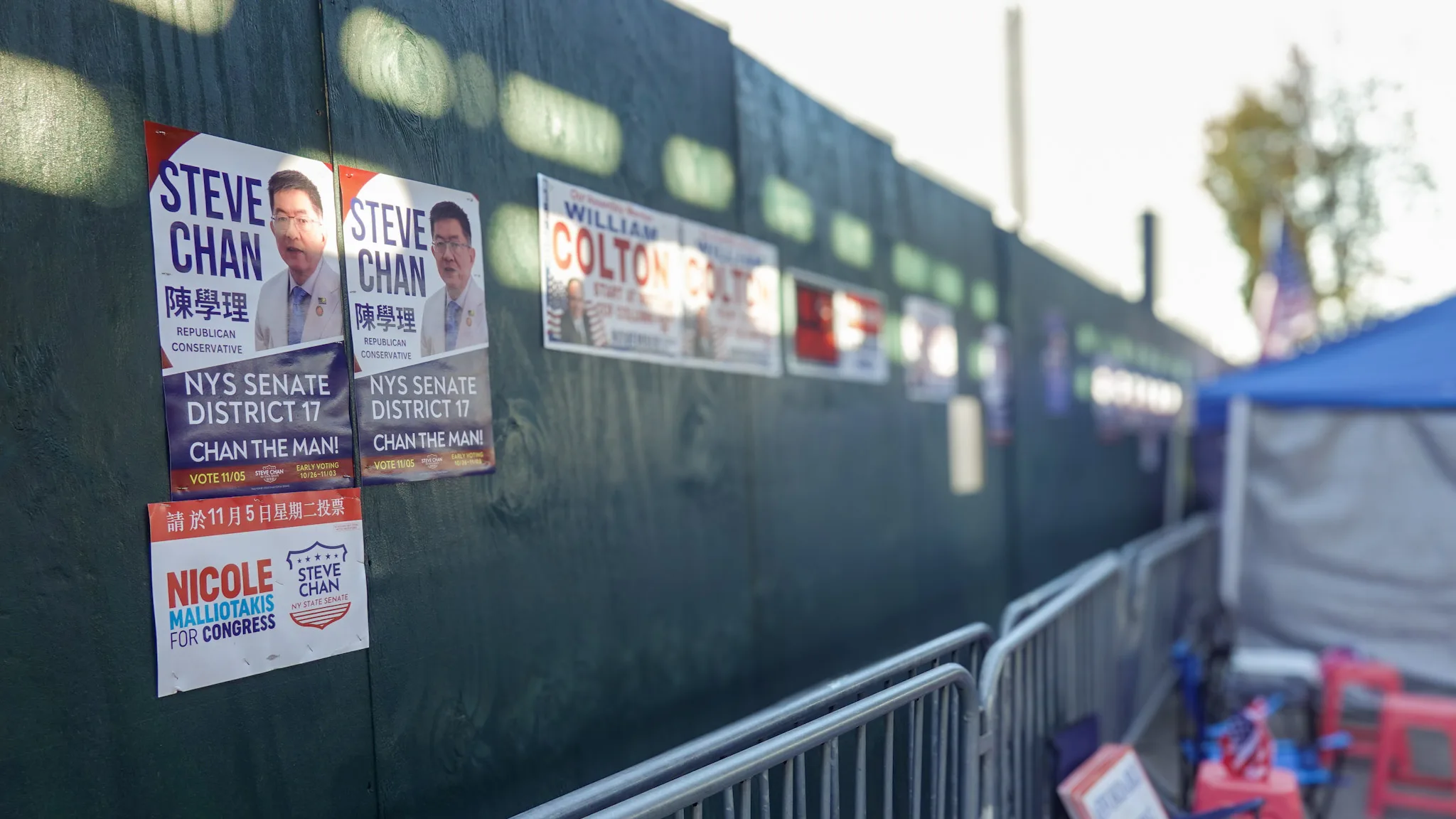

That hypothesis will be tested today, as voters go to the polls for the midterm elections. In the Democratic efforts to flip the New York State Senate and the U.S. Congress from Republican control, much attention has been focused on tight races for the 22nd State Senate and 11th Congressional districts, which cover similar areas of South Brooklyn and Staten Island. Yet the ultimate fates of the two legislative bodies may be sealed further east, in rapidly diversifying areas of Nassau and Suffolk counties where Latino voters could be decisive.

Make the Road Action, the political arm of the immigrant and Latino rights organization Make the Road, is one of the groups reaching out to Long Island Latinos in the hopes of an electoral payoff. “People feel under attack,” said its managing director, Daniel Altschuler. He pointed to Democratic victories in 2017 county executive elections in Westchester and Nassau counties as a sign of turning tides and the risks of alienating Latino communities.

Before Nassau County Executive Laura Curran defeated GOP opponent Jack Martins by three percentage points last year, the county had been led by a Republican for 40 of the previous 47 years. One of the Martins camps’ most significant missteps came in the closing days of the campaign, as the state Republican party sent out mailers with a photograph of three heavily tattooed MS-13 members and the assertion that Curran was “MS-13’s choice for County Executive.”

The move proved wrongheaded, as local activists and officials denounced the ad’s racism and got an opportunity to reframe the election as an extension of the national debate over President Donald Trump’s anti-immigrant policies. “For the candidates who ran on demagoguing on immigration, it backfired,” said Altschuler.

Efforts to activate Latino voters are now focused on: State Senate District 5, where longtime legislator Carl Marcellino is in a rematch against Democrat Jim Gaughran, whom he beat by about 1,500 votes in 2016, his closest race since first being elected to the State Senate in 1995; State Senate District 8, where Democratic Sen. John Brooks is defending his seat after defeating the incumbent GOP Sen. Michael Venditto by a mere 258 votes in 2016; and New York’s 2nd congressional District, where longtime GOP U.S. Congressman Rep. Peter King is facing a spirited challenge from outsider Democrat Liuba Grechen Shirley.

Both Nassau and Suffolk counties have had a growing Hispanic population in the last few years, together adding about 80,000 Hispanic or Latino residents between 2010 and 2016, according to data from the American Community Survey. The counties had about 230,000 native-born and naturalized U.S. citizens who spoke Spanish at home as of 2016, about nine percent of the total citizen population. Most of these people live in mixed-status households, where some family members are not U.S. citizens.

This population growth is apparent in the immediate surroundings of the Long Island Rail Road station at Copiague in Suffolk County. Businesses in the surrounding area display “Se habla español” signs, and Hispanic delis dot the streets. At around lunchtime on Sunday, a crowd of all Spanish speakers milled around a long counter where cooks were serving fried fish, quesadillas, and assorted Mexican and Latin American foods. Several cars driving down residential streets could be heard playing reggaeton.

It was to this and neighboring areas that a group of Make the Road Action volunteers fanned out in recent days, knocking on the doors of registered voters they consider to be of “moderate voting propensity,” that is, people who may have voted in the 2016 presidential election but are deemed less likely to participate in the midterms. Data they had compiled using the Voter Activation Network’s database estimated that about 53,000 Latinos had voted in Suffolk and 51,000 had voted in Nassau during the 2016 election, before dropping to 14,000 in both in the 2017 local elections. Canvassers are hoping to get that number up.

“Everyone is telling me they’re going to vote. Even the people that are undecided or don’t want to tell me who they’re going to vote for, they say they’re definitely voting,” said Cristina González, a Puerto Rican volunteer and political operative who most recently worked in Zephyr Teachout’s campaign for New York attorney general. That was a clear difference, she said, from previous cycles, when Latinos she spoke to were noncommittal.

One such noncommittal Latina was González’s canvassing partner, 20-year-old Mexican-American college student María Gómez. “In 2016, I was old enough to vote, but I didn’t,” she said. Horrified by Trump’s policies as the daughter of undocumented parents, she now feels differently and many of her peers have had similar rude awakenings, she said. With the news full of images of longtime community members being deported and families separated at the border, and “you feel like that could be you.”

That raw emotional appeal and sense of immediate, personal risk may be the only things that can overcome the structural trends among Latino voters, who have long been a hard constituency to reach. “It’s a very dismal situation when it comes to the Latino vote,” said Laird Bergad, the director of the Center for Latin American, Caribbean & Latino Studies at the CUNY Graduate Center. Bergad has been crunching the numbers on voting and demographics for years, and he said almost every Latino get-out-the-vote operation has ended in failure.

The trends in New York, Bergad said, mirrored trends nationwide, as increasing numbers of Latinos did not ultimately translate into larger voting blocs. “The absolute number of Latino voters has increased enormously, even though voter registration and participation rates have been fossilized, absolutely stagnant. Latinos are not exercising their political power, because over 52 percent of voters stay home,” he said.

He agreed with the canvassers that they could have enormous impact, but remains skeptical about their efforts in practice. Nonetheless, he conceded that the national political atmosphere is more charged and threatening to Latinos than it has been in recent history, and said he hoped he was wrong about his predictions.

Altschuler, of Make the Road Action, believes that this is a self-reinforcing cycle, where Democratic groups fail to commit the resources for comprehensive Latino-targeting efforts, and in turn, the Latino vote fails to materialize. “We’re out here knocking on doors, but if we’d had the resources to be out two months ago, we would have been able to knock on a whole lot more doors.”

For María Rubio, a Honduran who was involved in state Sen. Brooks’ campaign and works in cleaning services, the key is to turn feelings of persecution and disenchantment into empowerment and resistance. “Even though he will continue to be president, we have to stay in the fight… People are saying we aren’t going to come out to vote because we’re afraid, but I think there’s a certain kind of Latino pride, a feeling of ‘we’ll show them,’” she said.

During the time that Documented trailed several canvassers as they made their way around Long Island suburbs, everyone who opened their doors said they would be voting straight down the Democratic ticket. The targeting efforts were already apparent: often, candidate literature would already be on stoops and doors before canvassers showed up, and several potential voters already knew their polling locations and when they were planning on voting.

At one house, Rubio started explaining the purpose of her visit to an older lady who initially seemed confused. After a minute, she smiled. “Oh, the last group to come by already explained all of this! Yes, we’ll be voting,” she said brightly.