In February, Mayor Eric Adams’ administration announced that the city would distribute prepaid debit cards to migrant families to use at supermarkets, convenience stores, grocery stores and bodegas. The pilot program began rolling out on Monday, and by next week about 115 cards will have gone to roughly 460 people who are placed in 28-day shelter stays through the Department of Housing Preservation and Development.

With more than 180,000 migrants coming through city care since the spring of 2022, the Adams administration has faced criticism for spending tens of thousands of dollars on meals for migrants that were instead thrown away, or for food that allegedly made kids sick and sometimes was served spoiled. City officials said the cards could help minimize the costs incurred by the city, and Mayor Adams called the program “an important new form of saving taxpayers’ dollars.”

A City Hall spokesperson said in a statement Monday that the program was expected to save New York City taxpayers more than $600,000 per month and $7 million per year. Still, the announcement of the prepaid debit cards was immediately met with backlash, including from rapper 50 Cent and Texas Gov. Greg Abbott. On social media, some users falsely claimed that cards came loaded with $10,000; others wrongly called it a credit card and gave the impression that there were no limits on what people could spend the money on.

Also Read: NYC Grapples with Rising Tensions Over Asylum Seekers

To launch the program, the city contracted up to $53 million with Mobility Capital Finance (MoCaFi), a financial services company for low-income communities founded by CEO Wole Coaxum. MoCaFi will provide prepaid debit cards, called “Immediate Response Cards” (IRC), to migrants.

The amount of money that each family will receive on the card will be based on the family size and age of children, following SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) and WIC (Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children) guidelines. The city will begin by loading only one week of funds onto the cards at a time. As an example, a family of four with two children under five will receive about $350 each week through the end of their stay.

The card can only be used at places with the specific merchant category codes, and cannot be used to withdraw cash or ask for cash back. The IRC team will have an in-person station at the Roosevelt Hotel, where they will hand out the prepaid debit cards to asylum seekers after they have been assigned to a shelter.

In this Q&A with Documented, Coaxum spoke about how the debit card program came to be, and why it’s being implemented. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Giulia McDonnell Nieto del Rio: How did the idea for this program in New York City start and what were the conversations with the city like?

Wole Coaxum: MoCaFi as an idea started back in 2015. I wanted to figure out how to get high quality, low cost banking products to unbanked and underbanked individuals. We were able to bring that to fruition in Los Angeles in 2020 with something called the Angeleno Connect program, which was innovative in terms of this idea that if you want to help unbanked, underbanked constituents. Helping government become more efficient in terms of getting those resources to individuals, and it is an important way of creating real value for the city. It reduces their cost to serve, while improving the quality and the experience of the individual — giving individuals access to resources they can use immediately and then putting them on this path to economic mobility.

So when Mayor Adams was candidate Adams, he was going across the country, listening and learning about impactful ideas that could help the government become more efficient. We shared the Angeleno Connect program with his team.

Once he became mayor, he had a list of ideas that they had heard about during the campaign trail that he wanted to explore further. Separate from anything that we knew about, his administration reached out to the city of Los Angeles and said ‘Tell us about your experience with MoCaFi. And out of that, we started a conversation separate from the asylum seekers about how we might create this financial services infrastructure for New Yorkers. That put us down the path of coming up with a demonstration project, which would allow the city to experiment with both our demand deposit account and our disbursement account.

While those discussions were going on in the first and second year of the Adams administration, internally within the Adams administration — without our involvement — HPD had a conversations with different entities within the city saying, ‘Hey, we’ve got this challenge in terms of food delivery, it may not be the most efficient, are there other ideas?’ And it was brought to their attention that this demonstration project might actually be a way to solve the food delivery challenge. With that, HPD reached out to us and said, ‘We understand you’re working with another part of the city around bringing this financial services infrastructure, is there an opportunity for us to coordinate and take advantage of that innovation and technology?’ And we said, ‘Absolutely, that’s what we’re all about.’

Why did MoCaFi feel like this was something that you all wanted to take on?

I couldn’t think of a better use case for our platform than the asylum seekers. My journey to create MoCaFi was watching people in Ferguson, Missouri, after the death of Michael Brown, using their protests to voice that there was a lack of access to resources. I thought, you need an economic justice agenda with a social justice agenda. And providing responsible, high quality, low cost banking services to individuals was a way of addressing that economic justice agenda that complements the social justice agenda.

Ensuring that people who have come here to seek asylum have tools that allow them to access economic justice and economic opportunity just fits within the idea of the company. We want immigrant communities to feel that they have access to tools and resources that so many of us take for granted. So the asylum seekers are a part of our family of customers that we want to serve, who are not well served by the traditional and non-traditional financial services companies.

There’s been some controversy about the maximum amount of money that can be loaded on the card. Could you explain what the maximum amount is and how that works?

One aspect of the question is, what are the limitations of the Immediate Response Card (IRC) itself in terms of the account. The IRC account that we’ve created has a $10,000 limit in terms of total dollars that can be put on the card. The card itself is set up in such a way that you can’t take money out of an ATM machine, you can’t ask for cash back at the register, and individuals can’t put their own money onto the card.

But the asylum seeker program has made a determination that this card is going to go to families who are in the HANYC (Hotel Association of New York City) program, and that the amount of money that’s going to be put on the card is related to the SNAP and WIC equivalent for the participants. It’s going to be limited to the time that an individual family is in the HANYC program.

What would happen if someone tried to use the funds for something that does not adhere to the specific categories the card allows for?

Our experience has been that people use the funds for the purpose that they have been allocated for, and that these are responsible adults who have received a benefit so they can buy food that’s appropriate for their diet, culturally appropriate and fresh. We’ve disbursed over $100 million in these types of programs across the country, where people use the dollars as intended. Now, that’s not to say that someone may go outside of the expectation. It’s our responsibility to have ways of following up with families and finding out how they’re using those funds, and determining if they’re using them appropriately. But we’re relying on the fact that it’s limited in terms of where those dollars can be spent, and with giving the individual a clear understanding of the intention of the dollars. If we do come to understand that someone is abusing those dollars, we have the ability to remove them from the program and remove those dollars from the card immediately.

What do you feel are the biggest misconceptions about the program?

I think the biggest misconceptions about the program are: It’s a credit card, we are giving away cash to people in egregious sums, and that these dollars aren’t being spent anyway. But the money is being spent — it’s just a question of looking at how we can spend it more efficiently. What people are reacting to is even less about the program, and more about the political environment that we find ourselves in. That doesn’t even allow people to get to the level of detail to really understand the program, because they’re using just the concept as a way to support their own particular narrative. It’s hard to have a conversation about what the program is when a group of people are really focused on the politics of the situation.

What does the cost differential look like between the contracts that the city is using now for these kinds of services, versus your debit card program?

The city did their own analysis that suggests that this could save $600,000 a month for every 500 families that we’re supporting — which gets them to $7.2 million saved for a year. We feel very comfortable with that analysis. If the city decides to use the full capacity that’s been allocated, the savings could be greater than what they’ve described. But not only is it a cost savings, but it also gives people the ability to make better choices, and to have things that are appropriate for their diets. You’re putting money directly back into the New York City economy, and you have the ability to save money. And we’re not just offering debit cards. We’re integrating into this the overall system that’s providing the services for asylum seekers. We have people that will be on site, and we built a call center that is multilingual which has full availability to address the language needs of people.

How did the contracting process work for the debit cards?

We follow the contracting process to the letter. We went through the process with HPD, it was signed off by the city, then it had to be reviewed by the Comptroller. We then had to make adjustments based on that feedback, and answer questions. Then it went back to the Comptroller, who signed off on it and registered the contract. It wasn’t until we went through that entire end-to-end process that we were in a position to launch the program. So we are very cognizant about the importance of following the contracting process.

Under what conditions would the pilot be expanded?

The contract allows for $53 million of allocation for this program. The pilot is a subset of that total amount. We will start with the first people and get some feedback (depending on how we roll out the pilot, that could take a week to a couple of weeks). As we get comfortable with how folks are using it, and it’s working as intended, then the opportunity is to take advantage of the full allocation in the contract as quickly as possible. Like anything, you want to crawl, before you walk, before you run. The pilot is a crawl that leads to a walk, that then takes us to the full amount allocated in the contract. We want to make sure that we’re doing it in a way that ensures a good experience for everybody, and that we’re fulfilling the objectives of the program.

In total, the contract can be for up to $53 million, $51 million to be dispersed to migrants and $2 million for MoCaFi. So what would happen, for example, if that full $51 million isn’t used, or the city decides to stop the program?

It’s a pay as you go model for the contract. For MoCaFi, there’s a lot of work to set this up, and that’s ongoing in terms of supporting the programs, so we charge a program management fee. Those fees are $375,000, less than 1% of the $53 million contract. Basically you’ve put the infrastructure in place — you’ve got people in the Roosevelt Hotel, you’ve got a call center that works and can handle languages. After that, it’s a pay as you go model. So if the city spends $1, we make 3 cents, if they spend $1 million dollars, then we get $3,000. So it really is aligned with utilization to ensure that you’re not paying for something that you don’t use, but there is a basic cost to set it up because we’ve spent quite some time to build.

What was your reaction to this intense backlash that the program received from high profile people such as 50 Cent?

Caught off guard, quite frankly. I didn’t realize that this kind of program would solicit such a reaction. It was unexpected. But as we’ve gone through the last couple of weeks, addressing the issues that have come up, I’ve been really pleased with the fact that as a company, we operate with integrity, we operate within the rules, and we use sound business judgment. Once all the dust settles, that has become clear. Everyone has a right to their own opinion, and everyone has a right to express that opinion. But there is only one set of facts. And as those facts have become visible, the noise has begun to dissipate. What we’re trying to do is say: We are where we are, we have an opportunity to create efficiencies, and improve customer experience. We, as a company, are trying to fulfill our mission, and this is a great opportunity to do so.

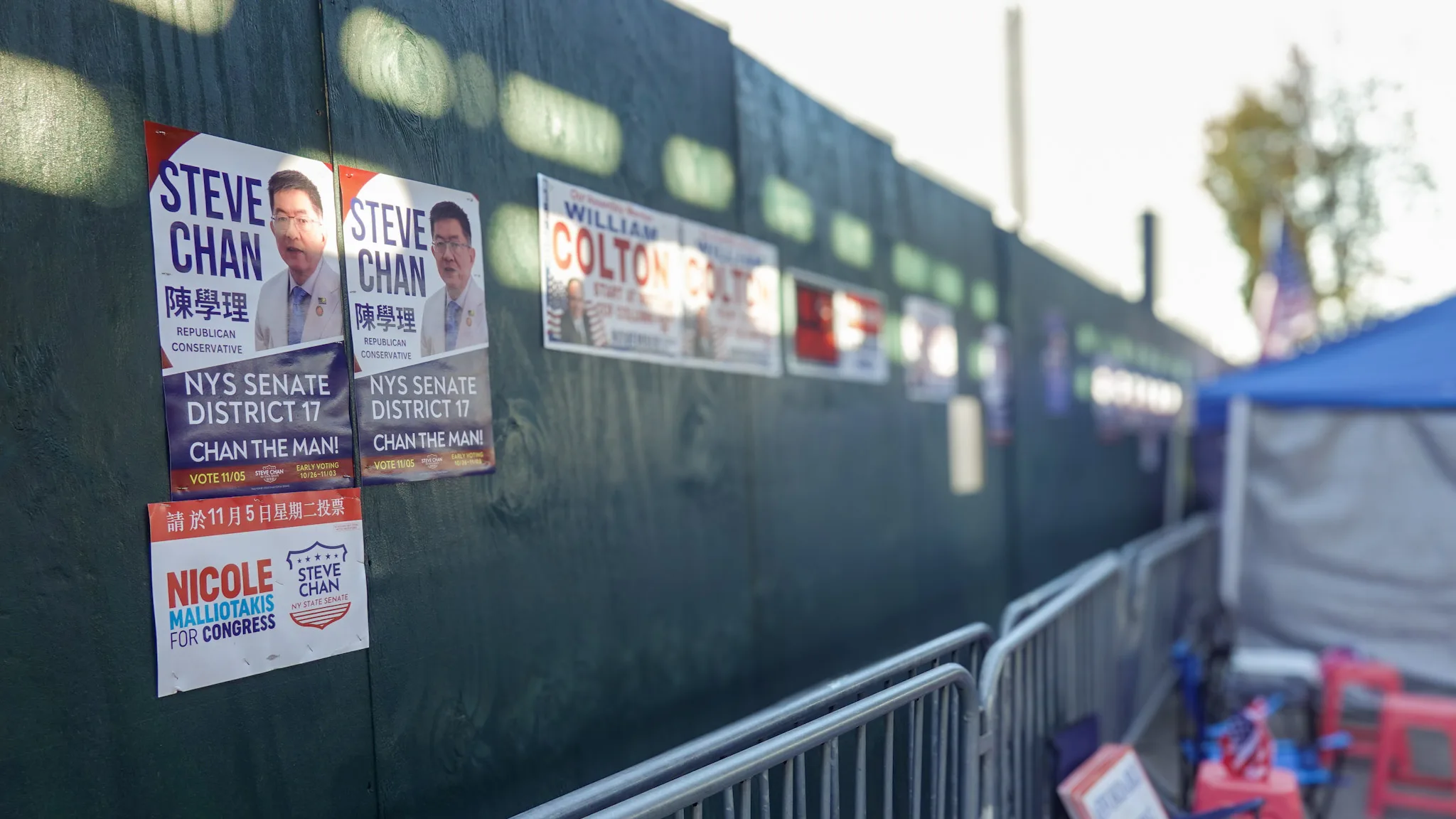

陈学理胜选凸显华人社区“右转”

You all have been speaking with Mayor Adams’ team for several years, since before he was elected, as MoCaFi developed programs to roll out across the country. How have these conversations with Mayor Adams and his team impacted — or not impacted — the way you look to do business with the city?

Mayor Adams and I have a purely business relationship. He described it well: He said, ‘I don’t go to the Hamptons with Wole, and I don’t go to baseball games with Wole.’ We don’t have that type of relationship. Working with city government, state government, federal government, that’s what we want to do. We think that our services allow governments to become more efficient and make communities stronger. Working with the Adams administration is no different than working with the Bass administration (Los Angeles), the Woodfin administration (Birmingham, Alabama), or the Jones administration (St. Louis). There’s a way that you work within the city framework in terms of the contracting process, and that is first and foremost in our mind. It hasn’t changed our interest in working with the city, in fact, it’s the opposite. It’s strengthened our enthusiasm and our resolve to get this done.

What are your biggest hopes for the debit card program in the future?

In the short term, our biggest hopes for the program are getting the resources out to people so that they can have better experiences and allow the city to save money. The broader hope is bringing a new framework that all New Yorkers can benefit from, in terms of access to resources. There are $5 billion dollars a year in New York City that are left on the table from the budget, for low and moderate income New Yorkers. Our biggest aspiration would be to help facilitate getting those dollars to everybody, whether they’re part of our immigrant communities, whether they’re part of communities all across the five boroughs, whether they’re a part of elderly communities — so that all people have the opportunity to tap into the resources. If our platform can accelerate that, that’d be terrific.