The only home Luke has ever known is a small room he shares with his older brother and parents at a hotel shelter in Koreatown. His mother, Viviana Guerrero, trekked across the U.S.-Mexico border while she was nearing the end of her pregnancy with him. Now, just 5 months old, he has quickly become a New Yorker — born soon after his mother’s arrival in New York City.

On a recent Monday, Luke squirmed and whined in his mother’s arms while they were at an Upper West Side church, but she clutched him tightly as she collected food and a stroller she had come to pick up for her children. Since they arrived in New York about seven months ago, the family — Guerrero, her husband, Luke and their four-year-old son — has been staying at the Koreatown Nyma hotel shelter. But life in New York isn’t much like Guerrero had imagined it, she said.

Guerrero, 31, flew from Peru to Mexico with her husband and child, and then crossed the southern border. When Guerrero was in Mexico, her family was kidnapped by cartels, she said. She was forced to ask her family at home to send $3,000, which they used to pay the kidnappers alongside some savings, for their freedom. “If you do something,” the men told them, “we’ll just shoot you.”

“I was just thinking of my son — hoping that nothing would happen to me because of him,” Guerrero said in Spanish.

At the Nyma hotel shelter, they feel cramped, with four of them staying in just one room with a single bed and a crib. Guerrero’s oldest son has grown tired of the shelter food, which is sometimes served spoiled, she said. He is often hungry, so she sometimes holds back on eating her meals to give them to him. Her husband has been able to find occasional work, she said, but it hasn’t been consistent. And like thousands of other recently arrived asylum seekers, the process to obtain a work permit is dragging out for Guerrero, obligating her to rely on city assistance for shelter.

“If we can obtain a work permit, then we won’t be that burden anymore,” Guerrero said.

Asylum seekers have been arriving in high numbers to New York City’s shelter system for more than a year now. As of last spring, more than 70,000 asylum seekers have come to New York, the city said this week, and over 44,700 — 60% of those who have already arrived — are currently in the city’s care. To handle the demand, New York has had to open more than 150 emergency sites.

“We are at a breaking point,” Manuel Castro, the Commissioner for the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs said at a news conference on Wednesday. “And without a real comprehensive strategy by the federal government, and adequate support to our city, this is just not sustainable. We don’t want people to show up at our doorstep and end up in the street.”

For the past several weeks, Documented has spent time speaking with more than 50 of these asylum seekers in all five boroughs — some have only been in the city for a matter of days when we interviewed them, and others have been in New York for more than a year. Documented interviewed asylum seekers from Venezuela, Ecuador, Haiti, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Senegal, Turkey, Colombia, Honduras, El Salvador, Costa Rica, and Peru. They told stories of traversing dangerous stretches of jungle, kidnappings, and injury among their loved ones before settling in New York. Many are working to find housing alternatives while their asylum cases are determined at the immigration courts, but say that the long waiting period for work documents stands in their way.

Across the city, the migrants we spoke to expressed gratitude to the New York City government for providing shelter and other assistance. But their stories also illuminated a lack of support systems at city shelters, forcing them to turn to outside groups for necessities such as fresh food, MetroCards, clothes, and access to laundry.

To accommodate the growing number of migrants, city and state officials have opted to use locations such as churches and former schools to shelter migrants, calling them “emergency respite sites.” Mayor Adams signed an emergency executive order on May 10 which temporarily suspended provisions of the city’s right to shelter law, including the prohibition of congregate settings for women and children.

Earlier this week, on May 23, Mayor Adams requested that a judge roll back parts of New York City’s long standing right to shelter law, which says the city must provide shelter to anyone in need. The Adams administration is asking to alter the directive’s wording, to permit the city to turn down adults or adult families asking for shelter during times of scant resources and capacity. Mayor Adams denied his administration was attempting to fully get rid of the right to shelter.

In a news conference Wednesday, Brendan McGuire, chief counsel to Mayor Adams, said he would not answer a question about what would happen if a judge granted the city’s request, and an adult family sought shelter after that. He said that the executive branch is looking for “areas of flexibility” so that it is not held back by the judicial order.

At a separate news conference on Wednesday, Mayor Adams defended the move. “I am leaving no stone unturned,” Mayor Adams said. “This is one of the most responsible things any leader can do when they realize the system is buckling and we want to prevent it from collapsing.”

Pleas for the federal government to step up and provide additional assistance have intensified in the past several weeks, as Mayor Adams and others question how long the city can continue to scrounge for housing. City and state elected officials have considered a wide range of open spaces to house asylum seekers, including former correctional facilities, former psychiatric centers, and schools that have been closed, among other options, they said.

Elected officials are stepping up their criticism of the Biden administration, and pressing the White House to come up with a pathway for expedited work authorization. In an interview this month with Documented, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez echoed the requests from local city and state officials, and asked the federal government to eliminate the waiting period for employment authorization after asylum seekers submit their applications.

Gov. Kathy Hochul and Mayor Adams have put up a united front, calling for the Biden administration to bypass Congress and take executive action on the work front to ease the strain on New York City.

“Having the right to work would allow us to take some pressure off of the situation so we can move people out of the care of the state and city, and move them into the stability that they’re looking for,” Mayor Adams said this week.

“There are lots of children getting sick”

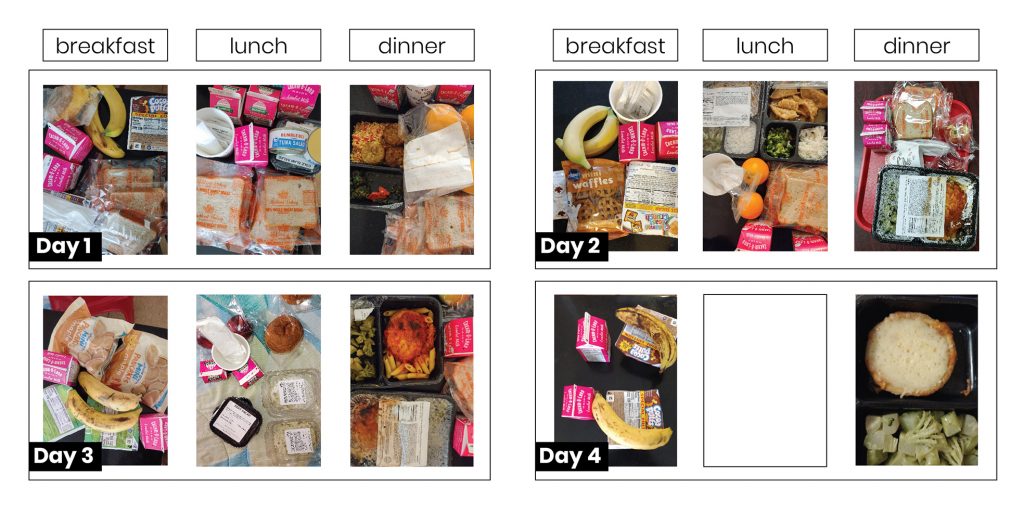

Vomiting, frequent stomach aches, and dealing with diarrhea for days. Parents skipping meals to give their allocated food to their hungry children. Taking a bite of a microwaved shelter meal, and quickly realizing it had already spoiled. These are just some of the situations that migrants eating the food at shelters described to Documented. The experiences have compelled many to depend on community groups or others who can offer alternative meals.

Brunilda Miranda, 40, has resided at the Starbright Family Residence in Brooklyn shelter with her husband, Roman, 27, for more than one year since coming to New York from El Salvador. Every day, Roman picks up breakfast, lunch and dinner for her downstairs at the cafeteria and brings it up to their room because Miranda is immunocompromised and does not feel safe eating with other residents, she said.

For more than six months, Miranda has been asking for accommodations to have a kitchenette placed in her room. Her doctor wrote her a letter requesting accommodations to prevent complications with her diabetes, Miranda’s lawyer Kathryn Kliff, a staff attorney at Legal Aid Society, confirmed.

“I was pre-diabetic for seven years and in the one year that I have been here, I am already diagnosed as diabetic,” Miranda said.

In Sunset Park, dozens of asylum seekers have been coming to Mixteca, a community-based organization, asking for resources not available at shelters. On Saturday mornings, Mixteca organizes a food drive which serves many who already live in the community, but which also caters to newly arrived asylum seekers. For the past few Saturdays, the line has stretched down the block on 23rd Street as more than 100 people have arrived early before the 10 a.m. start, to pick up bananas, broccoli, peppers and an assortment of other foods that can be eaten in shelters where families are not allowed to cook.

“That’s what we want — to give dignity with food,” Executive Director Lorena Kourousias said in Spanish at a recent Mixteca food drive. “We know that the community that is here is going through a lot of hardship. And we want them to at least have some food to take to their tables, and for them to know that with this food, we are here to support them.”

Migrants told Documented that they looked for food pantries, soup kitchens, and food donation events across the city to find alternative meals for their children.

Maryelis Perez, a 25-year-old migrant from Venezuela, was at Port Authority on a recent Monday, waiting for her partner who was arriving on a bus from Denver, as her children — who were 9, 5 and 1 — clung to her. She has now been in New York for about a month, and crossed the Darién Gap with her three children. She had to stay in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, for four months until she was able to cross into Texas and then flew to New York. They are staying at a hotel shelter in the Bronx, and she is thankful that her family has a place to sleep, she said, but her entire family has had difficulty handling the shelter food.

“My kids, they get sick,” Perez said. “The food comes out spoiled, it’s really bad.”

Perez, her partner, and her kids have become ill various times after eating, she said. She recently spent two days throwing up and dealing with major stomach pains after eating a shelter meal, she said, and her children have gone through similar illnesses, she said.

“It doesn’t seem okay to me — if the food comes out spoiled and it’s not the first time that happens, why do they keep bringing that food?” Perez asked. “There are lots of children getting sick, with diarrhea and nausea.”

A migrant family staying at a shelter in Long Island City, and a couple in a shelter in Brooklyn, shared photos of the hamburgers, boxed salads, and other microwavable dinners that had the branding of the vendor Whitsons Food Service, which currently has a $43,189,286.75 contract in progress with the Department of Homeless Services to renew its services for the next three years starting at the end of July.

And it’s not just a lack of adequate food that requires asylum seekers to look outside the shelters for resources.

Councilmember Gale Brewer, who represents District 6 in Manhattan, told Documented that New Yorkers have been dropping off food and clothing, and local churches and synagogues have been helping to fill some of the gaps in resources.

Some asylum seekers have to wash their clothes in the hotel bathroom tubs because the facility does not have laundry, and the families do not have funds for the laundromat, she said. The rooms are clean, Brewer said, but small. Brewer and her staff have been working every single day to meet the needs of migrants, she said, adding, “It never occurs to a city agency to reach out. They reach out to tell you that the hotel is coming. That’s it.”

Her office has picked up hot meals to bring directly to hotel shelters. They’ve set up a bank account through the Department of Homeless Services to collect money for asylum seekers. They’ve called the hotels to gather lists of what asylum seekers need the most. They’ve created flyers about clothes drives and book fairs in English and Spanish and brought them to the hotels.

“We don’t mind doing it,” Brewer said. “It just scares me that if there isn’t us, how would this happen?”

The Mayor’s Office did not respond to requests for comment about the food quality at shelters, concerns from asylum seekers about the conditions at congregate shelters, the lack of resources available directly at shelters, and questions about the number of people living at the respite centers.

Seeking support from overworked social workers

Miriam, a mother from Ecuador, arrived in New York about four months ago and is living in a Manhattan hotel room with two beds, along with her partner and three children. Miriam, who only shared her first name for privacy reasons, and her family are grappling with the memories of their journey through the Darién Gap. There, the children were constantly hungry, Miriam said, and pleaded with their parents to let them rest as they trekked through the terrain, watching snakes slither by their side. “I can’t go on, I don’t want to walk anymore,” Miriam, 32, remembers her youngest son telling her.

One of her daughter’s hands and feet became covered in welts during the trek, Miriam said, and the girl cried often, becoming sick with a fever and developing serious stomach issues. Now, Miriam’s 15-year-old daughter rarely eats the hotel shelter food. She sees a therapist every week, but they’ve been unable to find a psychiatrist. The daughter, who deals with anxiety, was on medication at home in Ecuador. But when she came to the U.S., she had to abruptly stop her medication and has been unable to find help to restart her medication since.

“It would be good to get some help,” Miriam said, adding that she becomes especially concerned about her daughter when they’re not together. “If she starts to feel bad at school, what am I going to do?”

At the hotel, most of the workers speak English, though a few speak Spanish, Miriam said. The family is hoping to move out of the city’s care soon, but they’re not sure when that might be. “We talk to the social worker and they tell us we just have to wait, and wait,” she said. “They don’t help us a lot in the hotel.”

Elizabeth, a social worker at a family shelter in Queens who asked to be referred to by her first name only for fear of retaliation from her job, said that some of the staff at her shelter have been neglectful in using the translation services available to help non-English speakers. “As I am the only Spanish speaker, I get people coming and knocking at my door, and I have to tell them that I can’t help them,” she said, explaining that the caseload in the past year has doubled for her from 25 to 50 families that she sees every week.

On multiple occasions last fall, Elizabeth woke at 4 a.m. to drive her clients from the shelter in Queens to their appointments with immigration authorities at 26 Federal Plaza. This is beyond the scope of her work, but the lack of legal assistance available at shelters and across the city, along with language barriers, makes her feel like there is no other choice.

“I’m worried about how sustainable this is for my career,” she said. “It makes me worried about how long I can stay in the shelter population due to how short staffed we are.”

Perez, the mother of three at a hotel shelter in the Bronx, said that there is no social worker at her shelter.

At Mixteca in Sunset Park, the staff has provided guidance for asylum seekers in all areas — from supporting them through mental health challenges, to providing basic necessities like food and clothes, and holding work training sessions, said Kourousias, the executive director. But still, Kourousias is concerned that there aren’t enough people or resources to alleviate the needs of all asylum seekers who come to Mixteca for assistance.

“It’s not a nice sensation, feeling like you don’t have everything that the people need,” she said.

Elizabeth added that obtaining childcare services has been one of the most-pressing obstacles families face at the shelter. “It is extremely difficult to enroll [children] into after school programs, and other residents in the shelter can’t watch their kids. So it leaves them unable to work, especially if they are single parents.”

Temporary respite centers lack resources

On a recent Monday afternoon, around six migrants, some from Venezuela and Senegal, stood in front of the St. Margaret Mary Roman Catholic Church in Astoria, Queens, where they were staying temporarily while the city worked to locate other shelters for them. J.M., a woman from Colombia, emerged limping from the church, holding on to her partner to keep her balance.

J.M. — who requested Documented only use her initials — explained that the church has three floors, lined with cots to accommodate dozens of migrants. Unlike traditional shelters which separate residents based on gender or family composition, the church where J.M. has been staying has been used as a congregate space. “I have a lot of anxiety being around men,” she said.

In her native Colombia, J.M. faced severe discrimination and harassment for being a member of the LGBTQ community, and traumatic experiences led her to flee her hometown. “I received death threats constantly,” she said.

J.M. crossed into the U.S. in July of 2022, and made her way to New York where she found a job as a hostess for an event company, which offered her housing and food. However, she was soon working 14-hour shifts at below minimum wage. She eventually left the job, and in May looked to the city for shelter.

The church was first used as a congregate space with single women, single men, and couples all together, J.M. said. But now the first floor has been designated for couples, and single men and women are on the upper floors. However, she said that the conditions are unsanitary and some residents smoke indoors.

“We are grateful for the shelter but we do not know how long we will be staying here,” J.M. said. Unable to find work, she says it feels like their “hands are tied.”

In the meantime, everyday at around 11 a.m., a group of 100 migrants, including J.M. and her partner, line up outside of the Astoria church and walk half a mile down 27th Avenue toward Astoria Park. There, near the pools, they take turns entering the temporary showers that have been set up by the city for the migrants. “It feels like a walk of shame, but we understand that we can’t be asking in this situation,” she said.

In Staten Island, a shuttered school became an emergency site for migrants arriving to the city, and asylum seekers staying there told Documented that it seemed like at least a hundred people were housed there. Migrants there told Documented that they slept in dozens of cots arranged close together across classrooms. There was no Wifi at the school, migrants said, so people wandered around neighboring streets, holding their phones up to find a free internet connection to contact their loved ones.

On a recent Wednesday, one table for health insurance sign-ups was set up in front of the school building. The lines to use the limited showers were often hours-long, there were no other clothes asylum seekers could wear apart from what they had brought with them, and the location was disorienting — far from potential work opportunities in other boroughs, migrants said.

Celeste Musiteke had been at the shelter for only a day when she spoke with Documented last week, and remained there more than a week after arriving. She is from the Democratic Republic of Congo, and made her way to New York after flying from Angola to Brazil, and traversing several countries north through the Darién Gap, finally crossing into the U.S. more than six months after she first began her journey. Without any family in New York, she is alone at the shelter.

“For me, the situation here is complicated,” Musiteke, 50, said in French about the shelter. “There are too many people in one room,” she added. “It’s like a hospital.”

She pointed at her clothes, the same ones she wore when she arrived at the shelter the previous day, because she could not find clean clothes at the shelter. More than one week later, she said she was yet to find any other clothes to wear. Sharing in a room with men she doesn’t know has been uncomfortable, she said, and she had not yet found staff who could speak French with her. “I’m very stressed,” she said as her eyes welled up with tears on the sidewalk outside the school. “It’s really difficult for me.”

Looking for assistance, on Wednesday morning, Musiteke rode the bus down Tompkins Avenue toward the Ferry Terminal to Manhattan. She boarded the subway, relying on her phone, and headed toward Harlem, to the non-profit African Communities Together. Musiteke, a nurse who dedicated her life to helping others, was now oceans and continents away, asking for help herself.