Chinese nationals are the fastest growing group of migrants arriving at the U.S. southern border, with official statistics stating that 37,000 were arrested there in 2023, 10 times as many as the year prior.

Despite their growing numbers, there is hardly any reliable data available to help paint a picture of who they are and why there has been such a sudden uptick in people from China choosing to make the perilous journey to a country some 7,000 miles away.

In an analysis paper released last week, the non-partisan think tank Niskanen Center pointed out that one of the few available official data sources that can offer some concrete demographic insights into this group is a rather unexpected one: the Ecuadorian international entry and exit registry.

Ecuador is the only mainland country in the Western Hemisphere that allows Chinese nationals to enter visa-free, making it the first arrival point for almost all Chinese migrants who go on to attempt to reach the U.S.-Mexico border.

Also Read: After a Treacherous Journey to the U.S., Chinese Asylum Seekers Find Language Barriers Hold Them Back

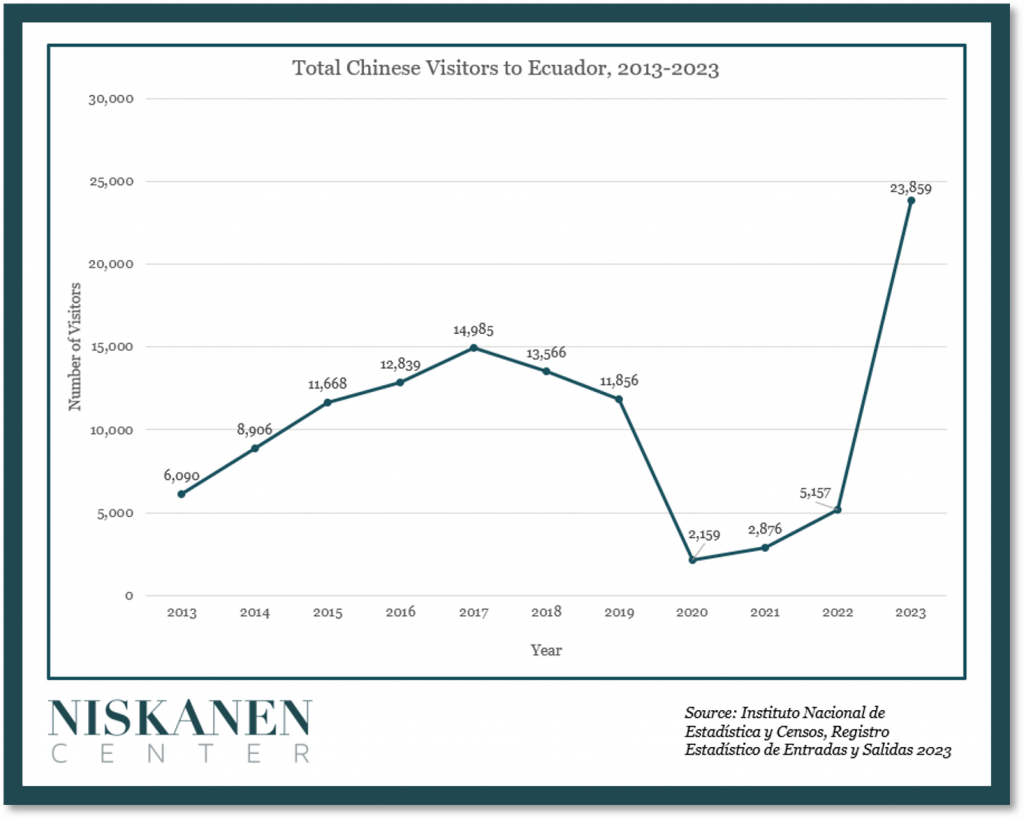

Niskanen argues that this means the country’s entry/exit records can be used to make more general inferences about this population and their characteristics. To back up the assumption, they point out that newly released records show that Chinese nationals entered Ecuador 48,381 times in 2023 but only left 24,240 times, leaving 24,141 individuals unaccounted for – the highest number by far for any nationality. Furthermore, a record high 23,859 Chinese nationals traveled to Ecuador at least once last year – a nearly 235% increase from the previous five-year average.

Their analysis of the past two years’ worth of data found that economic factors rather than merely political ones have likely pushed migrants to leave China. While regions like Hong Kong and Xinjiang were overrepresented as places of origin in the Ecuadorian entry data, Chinese “rust belt” regions with slowing economies and rapidly declining populations such as Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning also ranked among the top third tier of migrant hometowns.

Niskanen also found that most Chinese migrants are young and male, but assessed that this did not mean they posed any national security risk, as some politicians have claimed, often referring to them as “military-aged males” or spies. They explained their rationale by pointing out three social factors driving this group to take the risk of crossing the Pacific.

First, that men left single without hopes of a partner due to the gender imbalance created by China’s one child policy could be more motivated to strike out in search of new opportunities. Second, that social media has played a big role in making the complicated trip easier to envision and more logistically feasible. Third, the data shows that those heading to the U.S. via Ecuador are primarily middle-class, with 80% either high or middle-skilled professionals – and with only two out of the whole group listing “military” as their field of work.

To read more about the political factors driving Chinese migrants to the U.S. through Ecuador and what immigration policy reforms Niskanen recommends based on this new data, read the full report here.