This article is part of the Retorno project from the Guatemala based nonprofit journalism organization El Intercambio. It was funded by the Seattle International Foundation.

LA ESPERANZA, Honduras – In an old wooden house outside the city center, Suyapa Flores was surprised to hear the local branch of the Ministry of Education, which she runs, could have received extra funding because of a multinational initiative to decrease migration to the United States.

She asked an assistant to print the budgets of the last two years to check, but before she read the documents, she said she was confident they didn’t receive anything from the Honduran government. “We didn’t see any increase,” Flores said.

Juan Flores, head of the local Ministry of Health has also never heard of the Alliance for Prosperity in the Northern Triangle (A4P in federal parlance), the joint plan from the governments of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador to invest $5.4 billion to stop people from leaving. The plan also included a $2 billion investment of U.S. taxpayer dollars for the operation of federal agencies like USAID and the Department of Homeland Security within the three countries.

Flores runs his office out of a tiny blue hospital in the downtown area of La Esperanza. He was unaware of the increasing number of deported people in the area. Like Suyapa Flores, he was also sure that his budget hadn’t increased. To confirm, he asked three employees to verify and print the last two budgets: They hadn’t changed.

To interrupt the migration-to-deportation cycle, the Obama administration helped devise A4P in 2015. Money flowed through United States agencies and humanitarian aid contractors. Honduran public funding was supposed to reach the budgets of local agencies like Suyapa and Juan Flores, but it never did.

Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador committed to investing $5.4 billion, but rather than increasing budgets, only the names of government programs changed. The money never showed up in La Esperanza. The Trump administration cancelled A4P in 2019.

In 2018, the A4P arrived to the Department of Intibucá, the mountainous region of Western Honduras, where La Esperanza is the capital. With 65 homicides in 2018, Intibucá is among the five departments with the fewest homicides in Honduras. That’s one killing every six days. In Honduras, where 41 out of every 100,000 people were killed in 2018, that is peaceful. At the center of La Esperanza, murals commemorate Berta Cáceres, the Honduran indigenous activist and environmentalist, who was killed here.

To the surprise of local authorities and many of its residents, this town is undergoing a profound transformation: Over the past four years, La Esperanza has become the Honduran town with the highest rate of deportees from the United States. Here, A4P’s label was placed on expenditures from older budgets, and the new funds never appeared under the new programs, according to interviews with the secretaries of both institutions and the detailed budgets from the past two years.

“We dedicate funds to the reintegration of families of migrants and returned migrants, through seed capital, solidarity credit and work fairs for migrants. The plan [A4P] helps reinforce that,” said Nelly Jerez, the Honduran vice foreign minister of consular and migration affairs.

The Returned

The Municipal Unit of Services for Returning Migrants (UMAR, by its Spanish acronym) is located in an antique rose-colored house in the colorful downtown. The office opened in 2018 with funding from the International Organization for Migration and is managed by the Honduran government. It is essentially one woman at a desk in a shared office in the House of Culture, a two-story battered building with creaky wooden stairs.

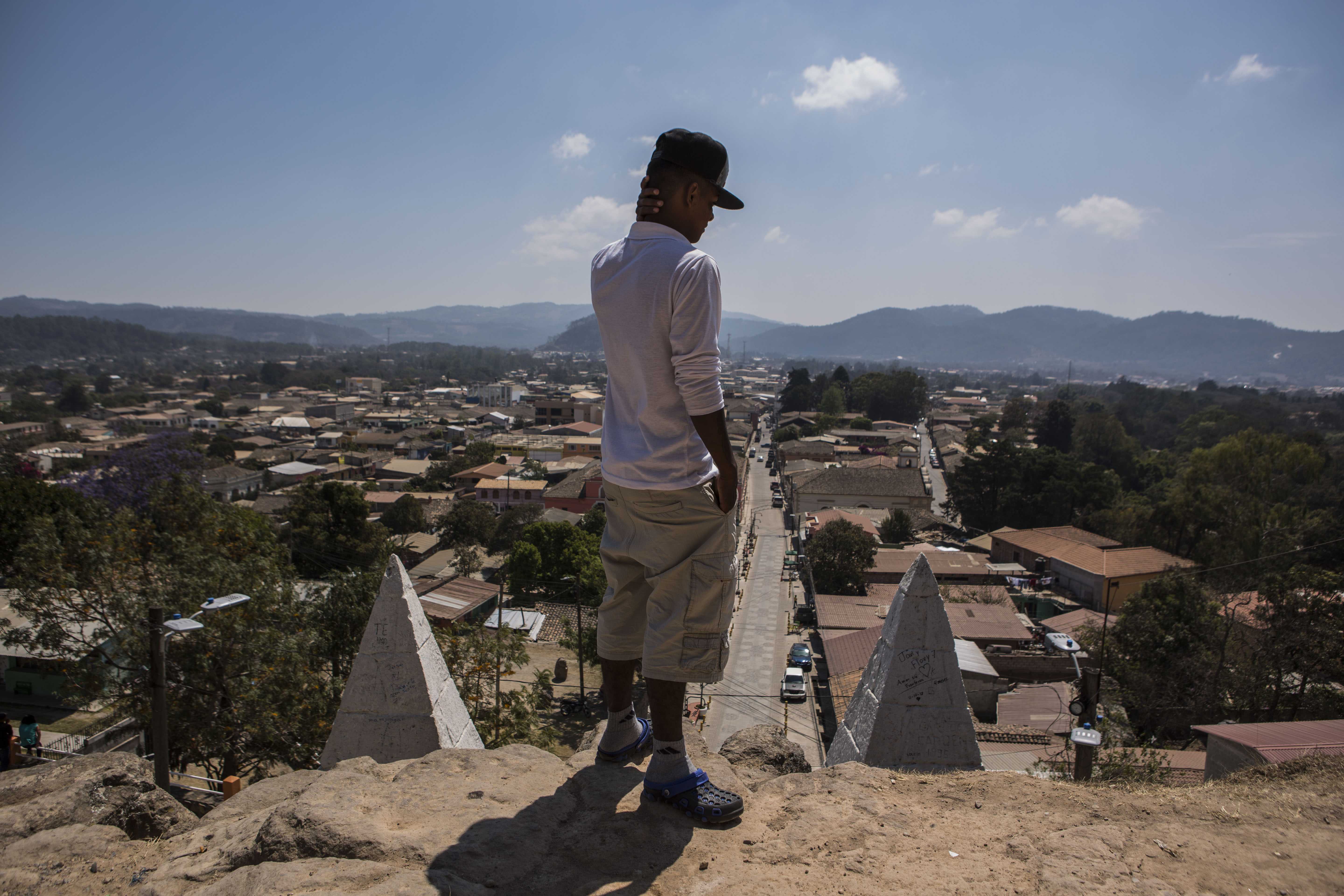

In 2018, the average retornado, or newly arrived Honduran deportee, in La Esperanza was 21-years-old. Among them is Torcido.

He appears among the files of retornados in that age group, registered under his aunt’s phone number in the neighborhood with the most deportees in La Esperanza, a city of about 14,000 residents.

Preferring to identify himself only by the Spanish word for ‘Wicked,’ out of fear for his own safety, Torcido recalled how he ended up in La Esperanza.

One day in 2018, the police showed up at a job site he was working in Lawrence, Kansas. They asked for his phone and his password, he recalled. “I had to give it to them. I had nothing to hide.”

He headed home, seething. He didn’t kiss his girlfriend, as he did every day upon returning from his temporary construction jobs around Lawrence. When his partner asked him to explain, he needed said to return to the police station to get “the damn phone.”

On his way to the station, he was arrested. In federal court, one of the officers accused Torcido – who was 20-years-old at the time, he said – of having a virtual relationship with a seventeen-year-old minor from the United States. They met on Facebook, but never in person. He admits the relationship, but he’s angry with the outcome it resulted in, with where he has landed now – a Honduran without legal residence in the United States.

The A4P was created for people like Torcido: young men with little economic opportunity who see no future where they live, other than leaving. But, the program hasn’t changed Torcido’s reality, or his desire to return to the United States. He’s never heard of A4P.

“In general, the governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras are responsible for creating the conditions in their countries that allow their citizens to feel secure and to prosper at home,” a State Department spokesperson for Western Hemisphere Affairs said in a statement.

Hundreds of thousands of Central Americans like Torcido flee to the United States due to poverty, food insecurity and violence. In the last year, the U.S. has detained almost one million people – many of them Central Americans – trying to illegally cross its border. The problem is far from new. Starting in the sixties, there have been many plans to prevent Central Americans from traveling north. The Trump administration has instead focused on forcing Central American governments to accept deportees and to crack down on migrants passing through their countries.

In 2017, the Honduran Ministry of Finance selected eight departments for the first A4P budget. It only weighed three factors in its selection: having an above-average homicide rate; proximity to a main highway or free trade zone; and a below-average employment rate. At the beginning of the plan, La Esperanza did not fit into any of the government requirements to get A4P money.

The International Organization for Migration detected the local increase in deportees, not the Honduran government. In 2014, La Esperanza received 307 deportees, according to Honduran government records. That these 307 people were deported means that they are no longer sending remittances from the United States, or they have debts to settle for their incomplete trips north. In 2018, two of every 100 people from La Esperanza were in the United States or on their way there.

None of this matters for Torcido, as he lays on the ground near La Gruta, a local landmark church chiseled into the face of a mountain. Torcido brushes the grass off his clothing and stands up to view the full panorama of La Esperanza. It’s a chilly day with a clear sky. From afar, he looks out on the town where he wishes he wasn’t. The Service Unit doesn’t even ring a bell to him. He doesn’t care that the government opened UMAR a year ago as part of A4P.

Local Struggles

The head of the local branch of UMAR doesn’t have the necessary funds to support the 17 of every 1,000 residents who have been deported from the United States, she says. She’s barely been able to help a half dozen in a year, and only thanks to local businesses looking to hire.

A psychologist by training, she says that her boss in Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras, refuses to allow El Intercambio to interview her or even publish her name. We tried to interview him days later, but he also denied that request. In La Esperanza, the woman in charge of UMAR said she recently helped a man get the same kind of job he had before he migrated, as a sports education teacher.

According to the Honduran government, UMAR is designed to reintegrate deportees into their community by providing psychological support, facilitating employment opportunities, and promoting family entrepreneurship.

But after a year of work, she says her biggest achievement as head of UMAR was that she helped a woman to get a place to sell food in the municipal market of Initibucá. Every day, she tries to contact deportees through the phone number they submit to the agency when they first arrive, but the numbers usually don’t work. Without a budget she can’t do fieldwork to look for them or pay for publicity about the office.

Unaware of the existence of an office, as most of the deportees in La Esperanza, Torcido is thinking about asking for help finding work and for information about existing tattoo removal programs, since he says he is not a gang member anymore. He was a member of MS-13 in the United States, but not in Honduras.

He says he would only travel in search of a tattoo removal program if his grandmother comes, because he believes they would kill him along the way. But in Honduras, free tattoo removal programs are scarce. Such programs did exist years ago, when a prior development plan paid for a contractor with a machine and had the funds to pay the employee who knew how to use it. The international press filmed the machine when it removed a tattoo.

Somewhere between reports, programs, and redrafting, funding for the program was struck.

This story was translated by Roman Gressier