The New York City comptroller is the city’s chief fiscal officer, the person tasked with keeping the city’s balance sheets and pension funds in good financial shape. In a city with a foreign-born population of around 40 percent, and in which immigrants make up an enormous amount of the small business owners and wage-earners, the question of immigration is inextricably tied to the financial well-being and viability. Comptroller Scott Stringer has been a vocal opponent of recent spikes in immigration enforcement and a more draconian federal immigration apparatus. He sat down with Documented to talk about the effects of current federal immigration policies and priorities on New York. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Felipe De La Hoz: Is your office already seeing a measurable fiscal impact from less welcoming immigration policies in Washington?

Stringer: New York City would not be this economic powerhouse without our immigrants. Every year, immigrants in the city earn $100 billion in income. Immigrants own 83,000 businesses, and immigrants are now throughout the economy, right? So it’s no longer the local store. We have immigrants in finance, in arts, in education. Forty-seven percent in technology; financial analysis, 44 percent; entertainment, 54 percent; medical, 50 percent. While that’s not the reason why we are outraged by Trump and the national agenda, because it is just inhuman, we have to also say: “We want immigration because it’s so powerful for our economy.”

De La Hoz: We’re seeing drops in the H-1B processing, drops in O visa processing, drops in F-1 visas for students coming. What will be the repercussions of that kind of a policy?

Stringer: From a business strategy perspective, an H-1B visa means that someone very, very talented is coming here, getting educated from the best schools, going into great jobs, and we make this investment in that individual, and then, because of flawed immigration policies drying up the visas, they go elsewhere and become our biggest competitors.

De La Hoz: Do you see the the share of wages earned and the share of businesses owned by immigrants on an upward trend that you think is going to continue?

Stringer: I think this Trump election has for the first time in a long time led a lot of us to question whether that will continue to happen. The notion that we would be outside 26 Federal Plaza because a man or a woman was detained from just checking in, this is something that Americans, New Yorkers, we woke up to this new reality. So I can’t say for certain that this kind of economic success story will continue unless we change what’s happening in Washington.

De La Hoz: There’s been a lot of talk about the census and the political climate, and the citizenship question that’s winding its way through the courts right now, about what impact that’s going to have.

Stringer: It’s huge on every level. It determines the amount of money we get from Washington. It determines our federal representation. There is nothing more important to New Yorkers than an honest, accurate count, and [with] this president… we are all worried about the validity of the census coming up.

De La Hoz: There’s the debate about the legal defense fund and the exclusion of 170 crimes for which the city may collaborate with ICE detainers. Would you support removing those 170 exemptions from—

Stringer: Yes, because at the end of the day, people are innocent until proven guilty, and everyone should have a robust defense. I think that is fundamental to a free society.

De La Hoz: Should the city be doing anything differently in terms of trying to regulate the entrance of immigration officers into buildings, like courts—

Stringer: This is the ultimate sanctuary city, and to the extent that I can make a contribution to protect people, I’m gonna do it. Going to church in Washington Heights and spending time with a woman who is literally a prisoner in the church with two little kids [Amanda Morales]. Just spending time with her, I mean, she’s not a free person. All she wants to do is just raise her family and live in this country. They will scoop her off the streets, and she’ll never see her kids again, and we can’t allow this to happen, and we have to do everything we can.

De La Hoz: Is there any gaming out that’s going on of what possible repercussions could be on different federal funding programs?

New York City immigration by the numbers:

Immigrants own 83,000 businesses.

670,000 New Yorkers are eligible for citizenship, but it can cost thousands of dollars.

The citizenship application fee is $720, up 500 percent over the last 20 years.

The City Council has adopted a $3 million dollar initiative to help people become citizens.

Immigrants earn $100 billion in income per year.

City Comptroller scott stringer

Stringer: That’s not a bad analysis to think about. I haven’t done it yet, but that’s a good idea.

De La Hoz: With the end of several TPS designations and no solution yet on DACA, the possibility here is that a lot of people that currently have work authorization and access to health insurance are going to lose it. What do you think the appropriate response from the city or Albany would be to stave off some of the impacts?

Stringer: Part of that is using every level of government. One of the things I’ve proposed is a citizenship [fund], to reduce the cost of citizenship. Six hundred seventy thousand New Yorkers are eligible for citizenship, but the cost of that could be thousands of dollars. The application fee is $720; it’s up some 500 percent over the last 20 years. The City Council has adopted this initiative, $3 million dollars to begin helping people become citizens, and now we’re putting pressure on the mayor to support this proposal in the executive budget.

De La Hoz: The citizenship fund idea, was that something that was brought to your office by some of the immigrant advocates?

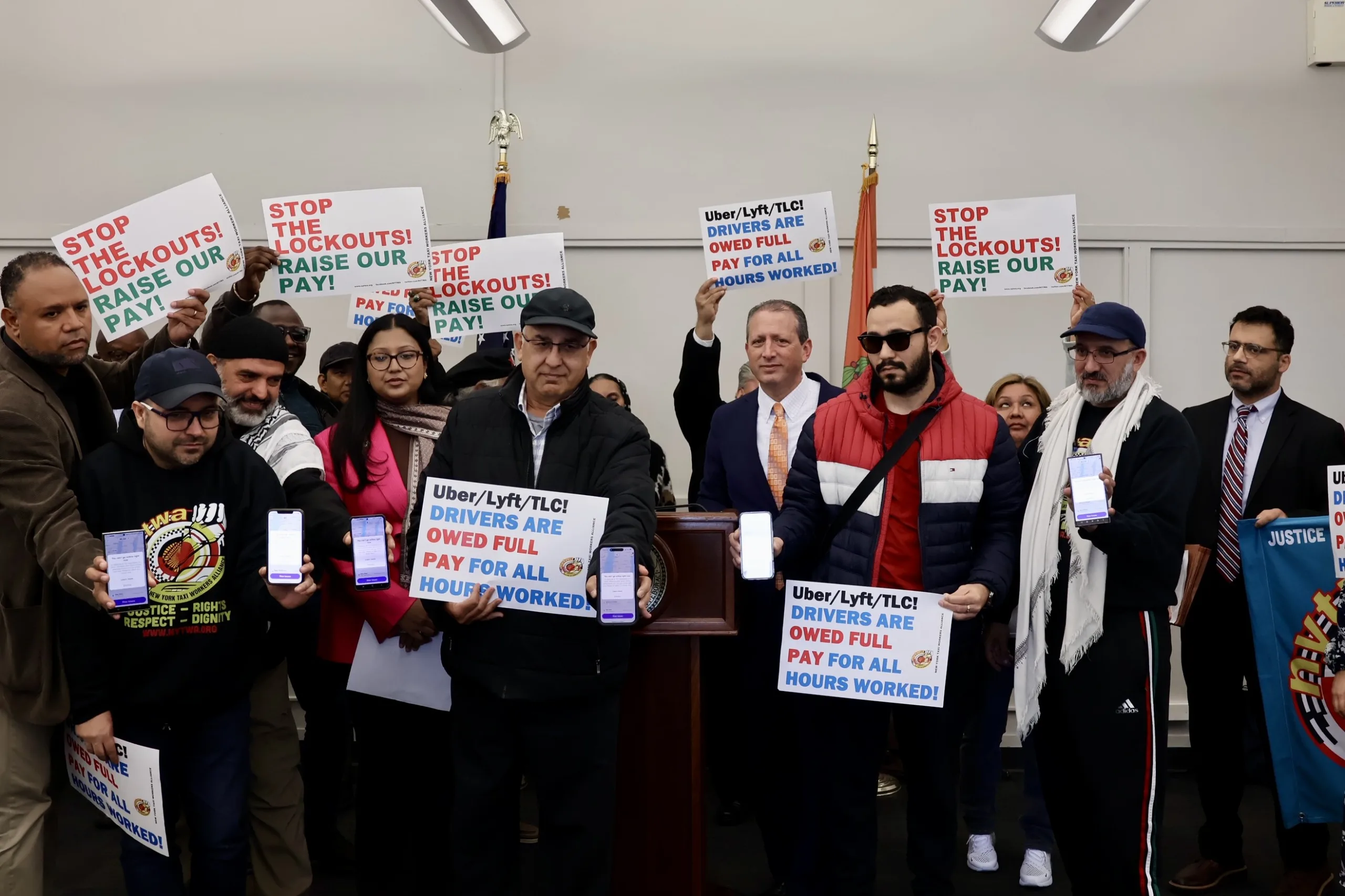

Stringer: I think every one of us who’s gone to the rallies, who has spoken at press conferences, written op-eds — whatever we’ve all individually done — we also need an action plan. Every office, whether it’s the mayor, the governor, city comptroller, we all should look at ways to promote responsible programs that are going to end up helping people.

De La Hoz: The department of health and mental hygiene had a report out, which stipulated that something like 50 or 60 percent of undocumented immigrants are uninsured, and the cost of that falls disproportionately on the public health system.

Stringer: Health + Hospitals is front and center to this crisis and the lack of funding to capture new immigrants who should be getting health care.

De La Hoz: I’m curious about your take on the way that the health system can keep functioning and keep providing the services that everyone requires without having to cut back.

Stringer: I commend the mayor for investing more in H + H. He’s put, last year, three hundred million dollars to keep it afloat given the uncertainty out of Washington. It’s hard to see that right now, beyond the fact that we have a fragile healthcare system with our public hospitals, but there’s definitely going to have to be a discussion of not excluding immigrants from the healthcare system, but how we deliver those services directly, because… you cannot keep immigrant families and their children out of the healthcare system. We will increase those costs eventually, because of the city we are, and that will be a burden on the budget.

De La Hoz: So you think there needs to be potentially an alternate delivery system for health?

Stringer: That’s easier said than done. What I try to avoid as comptroller is sweeping rhetoric. I look at it: How do we deal with this short-term? How do we get through the 2020 election?

De La Hoz: A lot of the big municipal unions refer to their large immigrant memberships. Do you have a sense of how much of the municipal workforce is vulnerable to some of the changes that are in the pipeline?

Stringer: I don’t have the data in front of me, but my sense is that a lot of folks get caught up in this war against immigrants, and with budget constraints in Washington and a Republican Congress that is anti-cities, anti-New York in particular, this is the collective pushback from labor, from the business community, from elected officials. None of us could ever imagine ICE agents coming into communities, rounding up people. I mean, it’s like from a different era. The thing that I’m trying to stress as comptroller is the power of immigration, and the power of immigrants in New York City has created an economy that is the best in the world. You really can come to this country with very little money, but with a lot of grit and hard work you can open a small business, contribute to the community, and raise your family. That is the immigrant story in 83,000 businesses, and it’s even bigger than that because the children of immigrants who started off with a small store, the next generation, from all different backgrounds, are now positioning themselves in a different way in the economy, as lawyers, doctors, people in entertainment, journalists.

De La Hoz: Something I know you investigate is people in the city feeling more empowered to prey on individuals with things such as wage theft, in terms of housing, threatening to call ICE on people and keeping the rent

Stringer: We decide the prevailing wage and we enforce the prevailing wage on construction projects. As comptroller, I have debarred the most contractors from doing business with the city. Over 70. So we have debarred companies that violate the law, not paying people prevailing wage, because I’ve taken the position where you cannot prey on innocent people. We have been able to track down people who, in some cases, were owed $20,000 to $50,000 working on a construction project. They got stiffed by the contractor, and we call up, find that individual, and I’ve had people right here outside getting a check at Christmas time for $20,000. They worked on these projects, and to give them back their money, I mean, it makes them believe in government.

De La Hoz: If and when the citizenship fund comes into existence, do you expect to be doing a lot of direct outreach?

Stringer: I hope so, if they’ll let me. This office, I like to think, is not the same office of our grandparents. The comptroller’s office has been the chief financial officer but also the advocate for the people who struggle in this city. Part of what we’ve been able to do as the first-in-the-nation pension is, we studied the issue of divesting our holdings from the private prison–industrial complex. These private prisons are basically turning into ICE detention centers and we became the first pension fund in America to divest. That resonated around the country, and this is the work we’re going to continue to do. We studied the impact on our pension fund, because I always have to say, and I do believe this, our first responsibility is to our teachers and firefighters and city workers and cops, but when we realized that disinvestment would not have a negative impact to the growth of our pension fund, we got the hell out of private prisons.