Ponciano Garcia exits the kitchen door of V&T Pizzeria and Restaurant on the Upper West Side. With a pizza box in hand, he unlocks his electric bicycle from the fleet chained to the scaffolding in front of the restaurant and pedals down Amsterdam Avenue. He’s back within 20 minutes.

Three years ago, that ride might have taken him longer. Garcia’s livelihood depends on his volume of deliveries; every minute counts.

His job got easier when he purchased an electric bicycle for $1,500. Now, he can go faster and farther, traversing a delivery area that spans the Upper West Side to Harlem to Hamilton Heights.

At the height of business, Garcia makes 10 deliveries per hour. That’s about $80 in tips per day, in addition to his minimum wage salary. The time that he saves by zipping through Manhattan on the e-bike proves critical when it comes to supporting his family of five.

Mayor Bill de Blasio has cracked down on e-bicyclists and the businesses that hire them as delivery workers. Immigrant–rights advocates say the increased enforcement unduly targets the 50,000 delivery workers in the city, many of whom are low-income immigrants. The crackdown has sparked a contentious back-and-forth between advocates and politicians, e-bike delivery workers, and concerned citizens.

Fifteen blocks south of V&T, Matthew Shefler rides his non-electric bicycle to the Central Park Tennis Center. Shefler is spry, wiry and in his 60s.

On the way there, Shefler says he took a shortcut by riding over a gravel path. Someone scolded him, telling him that he should be walking his bike. He acquiesced. After all, he knows the importance of bicycle safety.

Shefler is a vocal advocate of the increased crackdown on e-bikes in New York City. He says he has witnessed e-bike riders zooming down bike lanes, sometimes the wrong way. He complained, loudly, getting the attention of New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, who has since implemented stricter enforcement on e-bikes within the city.

Shefler and Garcia operate mere blocks apart, but in many ways, they live in different worlds — destined to cross bike paths, but never meet. Yet for both men, the existence of one is a threat to the other.

During Shefler’s bicycle commute through Central Park to his midtown office, where he works as an investment analyst, he says he has observed the chaotic style of e-bike (which he sometimes refers to as “motorcycles”) riders as they drive around the city. He expresses outrage. Shefler is a creative malcontent, frequently coming up with ideas that reflect his dissatisfaction with politics or policy or current events. Unhappy with Trump’s presidency, he has decided to perform what he calls a “civics lesson,” and see what he could do to effect change on a local level.

Confusing and contradictory laws on multiple levels of government regulate e-bikes. Federal laws control the manufacturing and sale of e-bikes, but the state and the city decide how, or if, they can legally operate. In New York, this means that it’s legal to buy and own an e-bike, but the vehicles are considered “motorized scooters.” According to New York City Administrative Code, “no person shall operate a motorized scooter in the city of New York.” Additionally, motorized scooters cannot be registered by the New York Department of Motor Vehicles.

On top of this, there are two different species of e-bike. The most common is the pedal-assist bicycle: essentially a regular bicycle with a motor attached that gives the rider a boost of power when they pedal. The other type of e-bike comes with a throttle, which allows the rider to have power without pedaling.

In the face of backlash from advocates, New York City reversed course on one part of the crackdown. On April 3, the city said it would allow pedal–assisted e-bikes. E-bikes that operate using a throttle are still illegal.

Last year, Shefler started attending community board and police precinct meetings to get a sense of how the local government worked. He began going out on the street with a $70 radar gun that he had purchased, trying to collect data about how fast e-bike riders were going. The data is flawed, Shefler admits, but he determined that many bicyclists went twice as fast as the 20 miles per hour speed limit that New York City imposes on bicycle traffic.

Shefler doesn’t go out with the radar gun anymore, saying that he just needed a “gizmo” to draw initial attention to his cause.

His publicity stunt did just that. WNYC did a feature on Shefler and his effort as part of a series about people trying to enact change in the wake of the 2016 election. Later, the radio station played a recorded question from Shefler for the mayor. He asked why enforcement focused on targeting the individual riders, rather than the businesses that used e-bikes.

“That makes a lot of sense to me,” de Blasio said. “I’m intrigued to say the least. I think there’s a real option to do something here.”

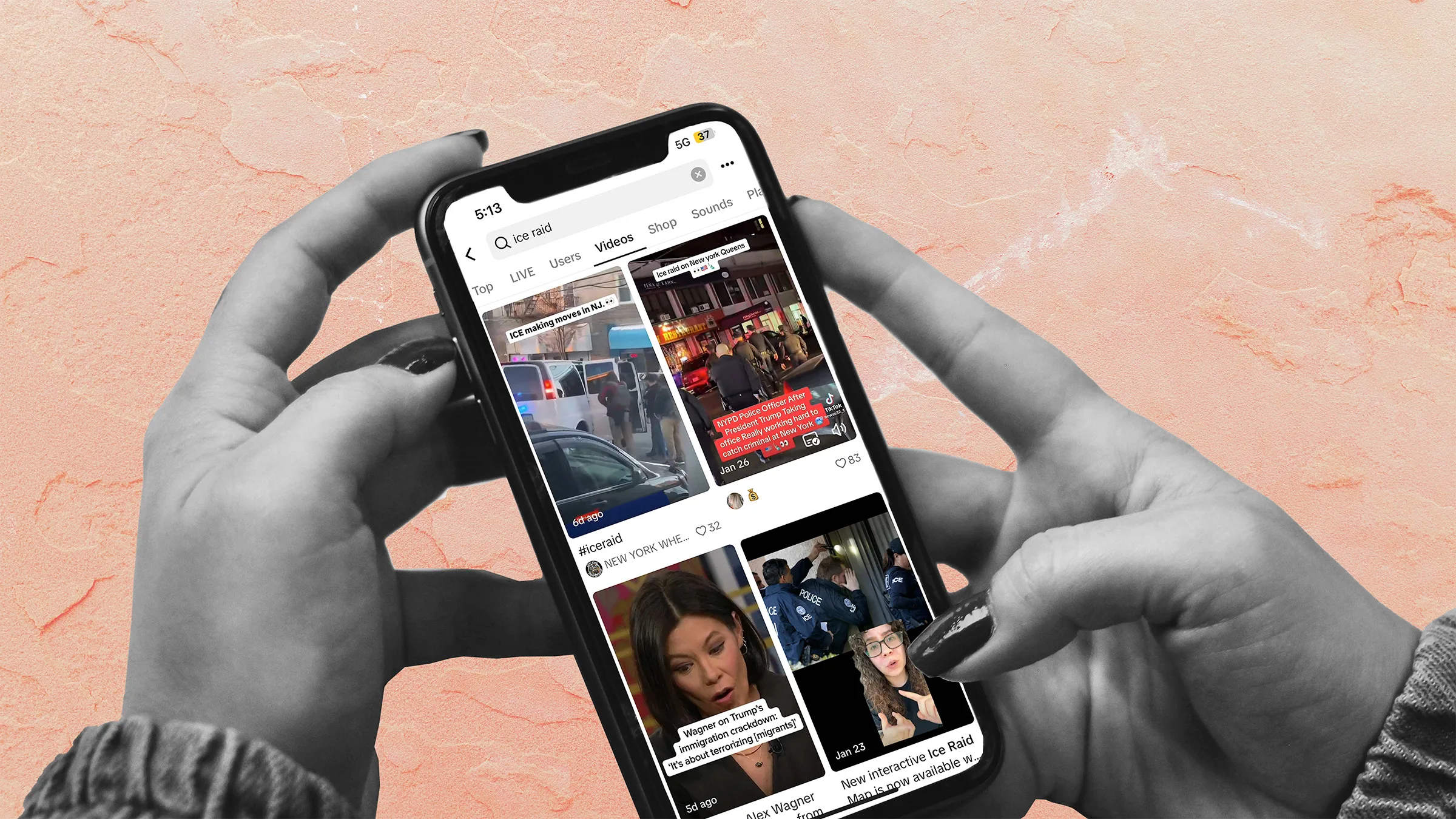

The NYPD has been targeting e-cyclists since 2012, when it created the Commercial Bicycle Unit as a new enforcement team, delivered citywide forums to delivery bicyclists and conducted door-to-door outreach at restaurants that employed bicycle delivery workers. In 2016, NYPD increased their efforts, conducting stings across the city and posting pictures on Twitter of officers posing with the bikes they had confiscated.

Shefler’s proposal fit in with the existing crackdown, as well as with de Blasio’s Vision Zero initiative, aimed at reducing traffic fatalities within the city. At a news conference held in October on the Upper West Side, de Blasio introduced the additional element of penalizing the business owners as well as the delivery workers.

“Those at the top of the food chain need to be held accountable,” de Blasio said.

Yet New York City’s resistance to e-bikes is something of a conundrum. There’s little data to support the opposition because police departments usually group e-bike accidents in a broader category that includes regular bicycles. In the Upper West Side’s 20th Precinct, out of 58 documented bike crashes in 2017, only one involved an e-bike, Gothamist editor Christopher Robbins reported.

E-bikes, which run on battery, are more sustainable and environmentally friendly than cars and are cheaper to buy. New York has been feeling the pressure to weaken the laws on e-bikes, especially in the face of the city’s goal to double cyclists by 2020 and the impending closure of the L train tunnel under the East River, set to occur in April 2019.

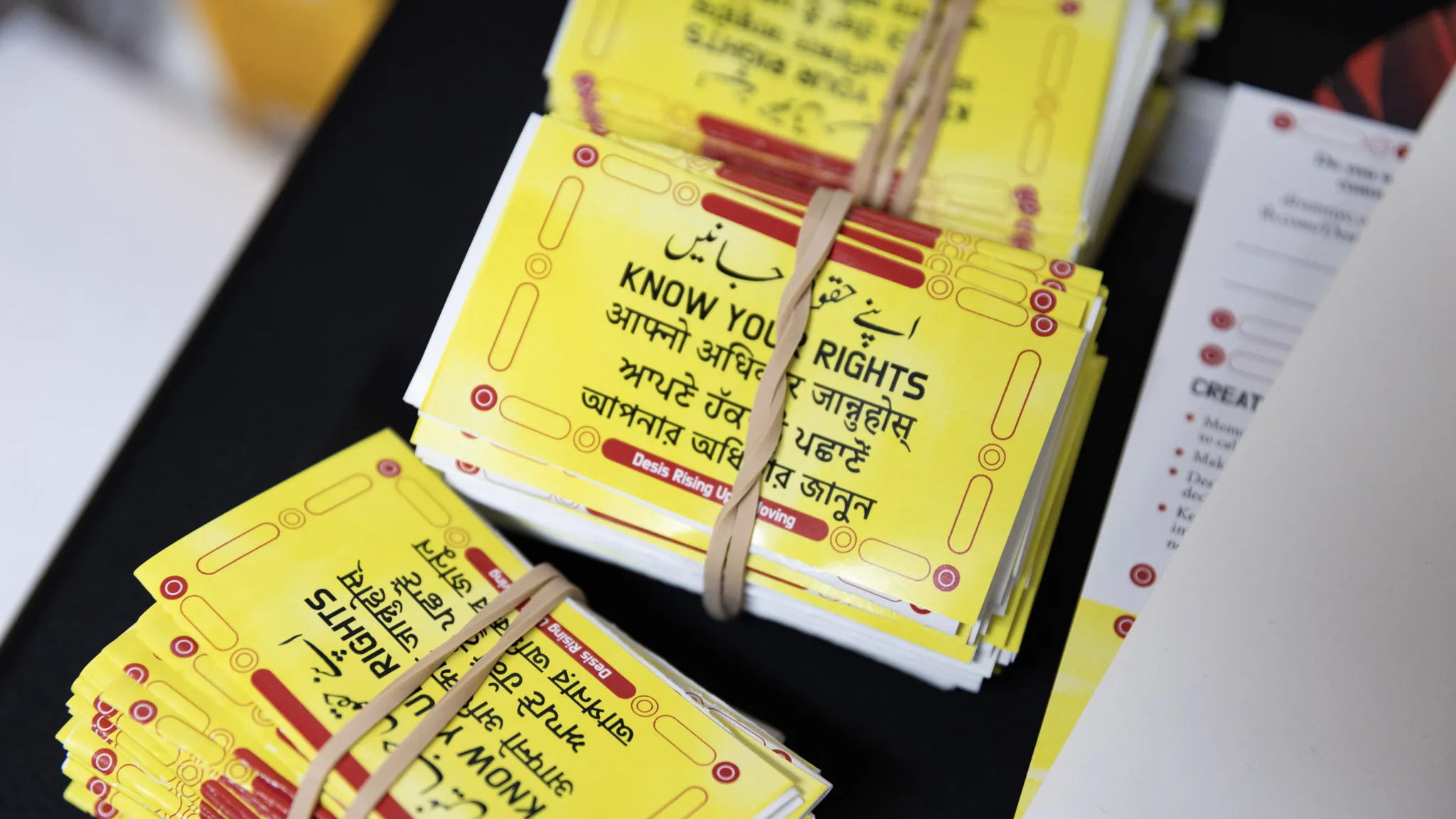

The crackdown has sparked a flurry of protests. Op-eds claim that the increased enforcement is racist because it targets immigrant delivery workers, and a rally was held outside City Hall held by the Asian American Federation, Biking Public Project and Transportation Alternatives.

“It’s a poor use of resources from the city’s perspective,” said Thomas DeVito, director of advocacy at Transportation Alternatives. “It also goes against a lot of broader principles that the city holds, as being a safe place for people to come of all backgrounds.”

Shefler insists that the crackdown is not an immigration issue, but just part of keeping New York City’s residents safe as bicycling increases in popularity and technological changes allow bicycles to go faster.

He remembers a chase he witnessed, with a police car in pursuit of an e-bike. Shefler estimates the e-bike was going 45 mph. He found out later that the police were never able to catch the speeder, and when he thinks of this, he has trepidation about riding his bike around town.

“I don’t want to be in these bike lanes during feeding times,” Shefler said. “It’s just not safe for me.”

Some restaurants on the Upper West Side have been targeted by law enforcement, but V&T manager Anthony Gjolaj says his restaurant and its workers haven’t been ticketed. Nonetheless, in the face of the increased enforcement, V&T told their delivery workers to keep their heads down, and especially not to run any red lights.

Delivery workers can face a hefty $500 fine just for riding their e-bikes. If their bikes are impounded, they spend valuable time trekking to far corners of their boroughs to reclaim their vehicles.

Shefler, while emphasizing that this is a safety issue that doesn’t involve class or immigration, says he has considered the effects on immigrants.

“Am I aware that I live on the Upper West Side and I’m biking to work and I don’t have to do this for a living?” Shefler said. “Yeah I am. But I’m also aware that I can’t take shortcuts.”

Gjolaj said that V&T’s five e-bike delivery workers use throttle and not pedal–assisted bicycles.

“We told [the workers] it’s time to switch over to pedal,” Gjolaj said. “If they get a ticket, we get a ticket. But honestly, we haven’t seen a major effect since the law passed.”

Meanwhile, the cycle continues. It’s early evening — the start of rush hour and dinnertime. Garcia waits outside the door to the back kitchen of V&T, savoring the unexpected warmth of the day. From inside the restaurant, someone bangs on the door, summoning him inside to get a delivery.

“In New York, life passes rapidly,” Garcia says. “It’s the city that never sleeps.”

He comes back out carrying two bags, unchains his bike, walks it down the sidewalk and disappears around the corner.