A judge ruled on Wednesday night that Immigration and Customs Enforcement had been improperly keeping Pablo Villavicencio, a pizza deliveryman who was detained at a Brooklyn army base last month, in a form of custody even after he was ordered released.

Villavicencio, a father of two, was detained by Army civilian police and turned over to

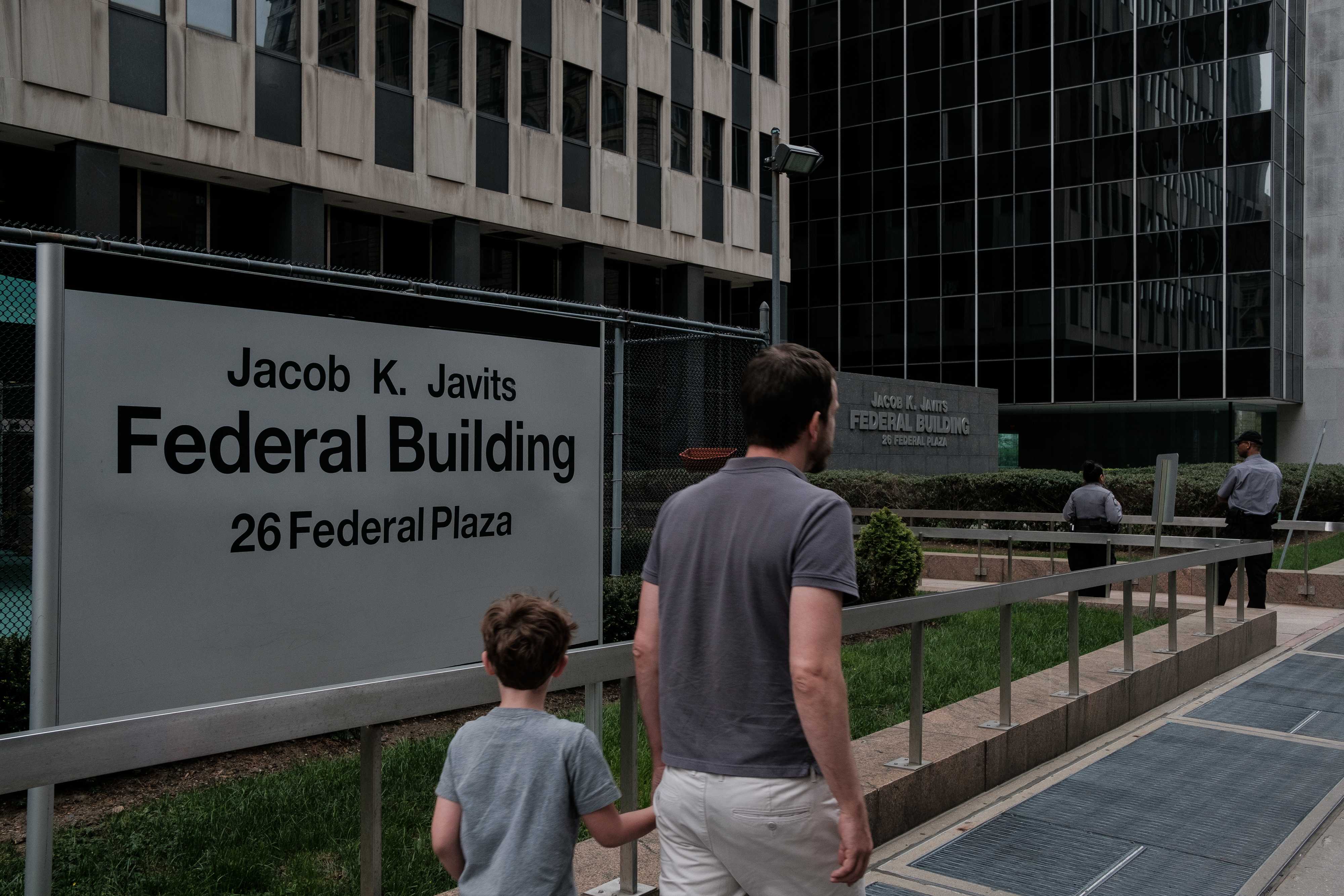

ICE while delivering food to the Fort Hamilton base in Brooklyn on June 1. U.S. District Judge Paul Crotty ordered his release from custody on July 24.

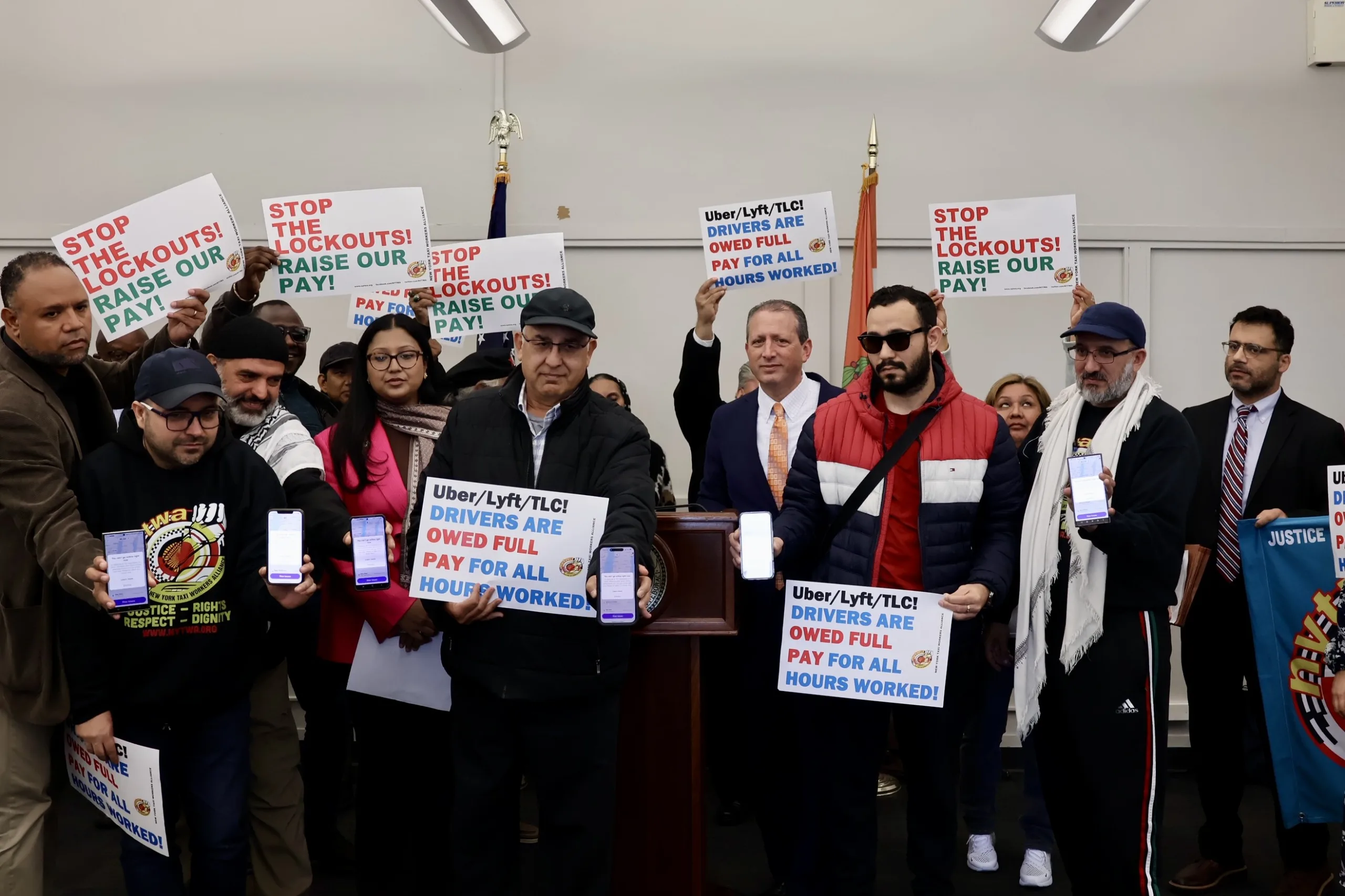

Gregory Copeland, one of Villavicencio’s attorneys at the Legal Aid Society, said that it had become a pattern lately for the government to issue orders of supervision (OSUP) — a mechanism used to impose conditions of release when people with final orders of removal — to clients that federal judges released without such restrictions.

“It has been pretty heavy-handed. There’s been an intimidation, a bullying quality to this,” he said, adding that Legal Aid had three clients in the same situation recently. They include Xiu Qing You, who was detained at a green card interview.

Villavicencio, who is originally from Ecuador and lives in Queens with his wife and two young daughters, had received a final order of removal in 2010, meaning he was ordered deported at the time. However, given his marriage to a U.S. citizen, he had started an application in February of this year to change his status to a legal permanent resident.

Citing his order of removal, ICE moved to deport him after his arrest at Fort Hamilton, but his attorneys at the Legal Aid Society and the firm Debevoise and Plimpton filed suit at U.S. District Court of the Southern District of New York, arguing that he had a right to see his current immigration applications through. This would include the processes to be certified as a family member of his citizen wife, to be permitted to reenter the United States, and to obtain a provisional waiver of inadmissibility. This waiver would allow him to travel abroad in order to regularize his status without triggering the 10-year ban on reentry that typically applies to people who were in the country for over one year without documentation.

The judge agreed, and, given that a removal would prevent this process from taking place, ordered the government to stay his removal until his applications were either approved or denied, and to “immediately release [Villavicencio] from custody because removal is no longer reasonably foreseeable.”

After he was ordered released, Villavicencio was not permitted to leave the Hudson County Correctional Facility, where he was being held, until he signed a copy of the order, which was signed under the authority of ICE New York field director Thomas Decker. The OSUP, a copy of which was provided to Documented, lists multiple conditions, including that Villavicencio has to check in with ICE personnel on command, cannot associate with gang members, and, crucially, that any violation of the order could result in him being taken back into ICE custody and criminally prosecuted.

Copeland said that, because of the government’s previous use of OSUPs for clients released under federal court order, Villavicencio’s lawyers preemptively asked the government to discuss a potential order, but were rebuffed.

“Being put on an OSUP has some benefits,” he said, such as making it easier for clients to receive work authorization. However, he views the conditions listed on Villavicencio’s order as more of an attempt to threaten him. “You can’t, ‘associate with a gang member?’ How vague is that? What if you don’t know someone’s a gang member and you’re caught associating with them? What is ‘associating?’”

In a letter to Crotty, the government, represented by the office of U.S. Attorney Geoffrey Berman, argued that it was within its rights to issue the OSUP under the Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 U.S.C. § 1231, which authorizes the government to release people with final orders of removal under terms of supervision. Villavicencio’s attorneys countered that the judge’s order of release was unqualified and that sections of the immigration law that the government cited applied when an immigrant was released by officials within the executive branch pending deportation, and not when they were ordered released by the federal court with no foreseeable prospect of removal.

The judge ruled in favor of Villavicencio, writing in an opinion that “the Order of Supervised Release by ICE would be in conflict with the Court’s Order to release [Villavicencio] from custody. ‘Custody’ in the context of a federal habeas statute includes supervised release.”

Copeland said it’s the first such decision the Legal Aid Society has obtained, and he hopes the order will from now on compel the government to negotiate or refrain from issuing OSUPs in the relatively rare cases of immigrants being ordered released by federal judges. Attorneys have sought a similar dismissal of the OSUP in the You case. Other prominent cases, such as that of New Sanctuary Executive Director Ravi Ragbir, feature orders of supervision.

A spokesperson for ICE did not have an immediate comment on the development.