Crispin Hernandez doesn’t want to talk about his personal life. He’s originally from Mexico. He’s 23. Everyone asks him about his favorite food, he says, but he doesn’t want to talk about that either, because you can’t find it here in New York.

What he does want to talk about is the potentially groundbreaking court case that has dominated his life for the past two years. Hernandez is fighting the New York Farm Bureau, which represents agricultural interests, to win the right for farmworkers to organize for collective bargaining without retaliation. State Supreme Court Judge Richard J. McNally, Jr. dismissed his case at the state Supreme Court in Albany in January, but the New York Civil Liberties Union, which represents Hernandez, has appealed the judgment.

Hernandez and his lawyers are seeking a ruling that the 1937 State Employment Relations Act violates the New York State Constitution by excluding farm laborers from the protections it extends to other workers. A ruling in their favor would allow all 60,000 agricultural workers in New York, most of them immigrants, the right to collectively bargain without fear of punishment.

Hernandez found himself at the forefront of this issue after he was fired from Marks Farm in Lewis County for complaining about the conditions and trying to organize employees. He says that he chose to spearhead the movement because he wants to improve the conditions for his agricultural compañeros all across the state.

“It’s not because I want to be famous,” says Hernandez, waving at a car that honks at him as he walks along the street in Syracuse.

Hernandez is fighting for the backbone of a colossal industry. Seven million acres of land are used for agricultural production in New York. The state is the top producer of yogurt, sour cream and cottage cheese in the nation; and the second highest producer of apples, maple syrup, cabbages and snap beans. As of the last agricultural census in 2012, the industry produced over $5 billion in sales.

In such a huge industry, life can be brutal for for its workers, who have an on-the-job fatality rate 20 times higher than the average worker in New York state. Overtime compensation isn’t guaranteed. Farmworkers who testified during the Hernandez case said that they lived in trailers without heat in the cold upstate winters. Many farmworkers said they have no regular access to transportation — drivers come to the farms to transport them to nearby towns for groceries, always for a fee.

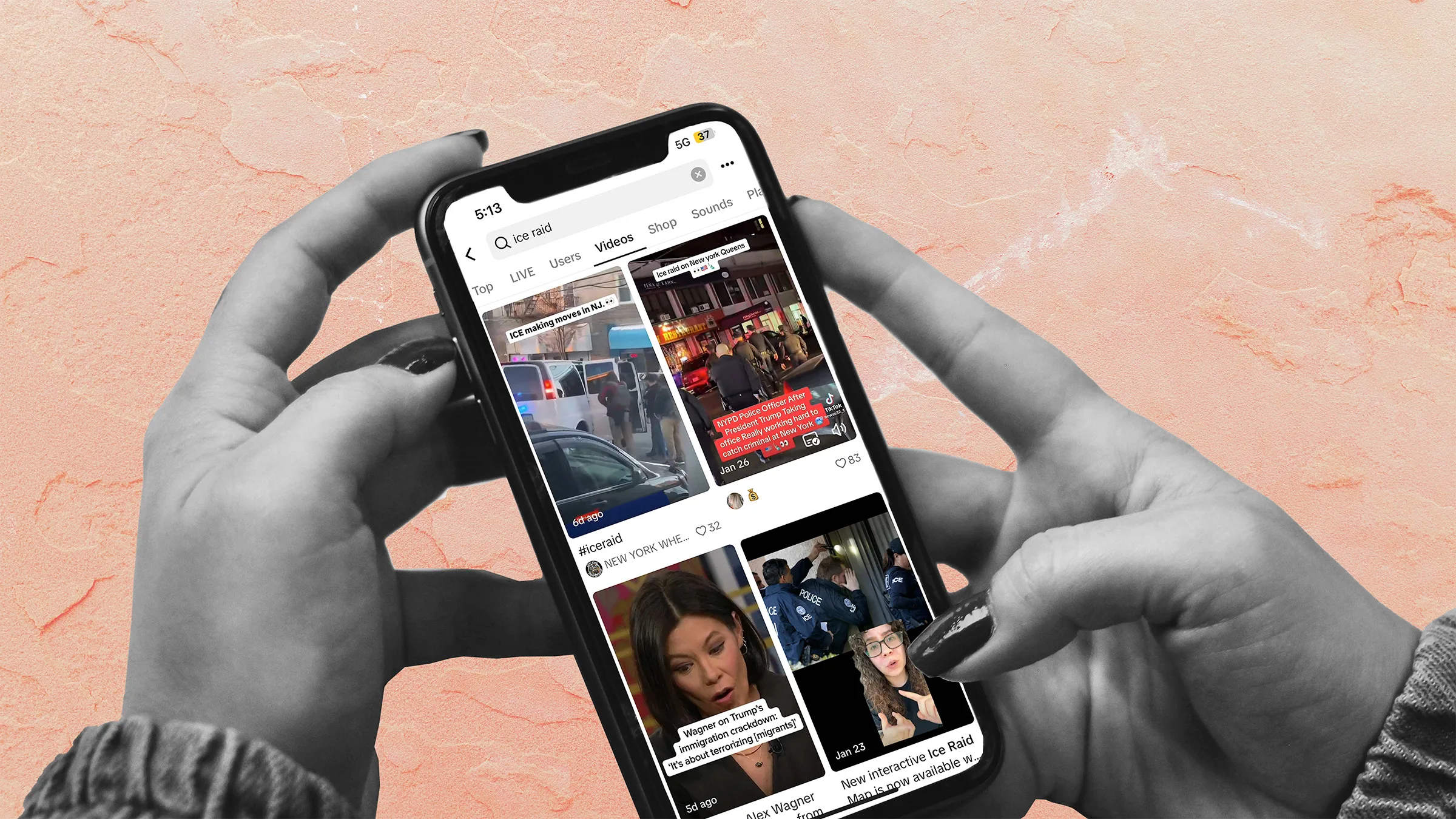

It can be difficult, workers say, to protest their conditions. According to the Survey of Hispanic Dairy Workers in New York State 2016 by Cornell University, 56 percent of workers don’t speak English well. Only half have completed between 9 and 12 years of formal education. Data from a survey conducted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture shows that around half of all farmworkers working in the U.S. are undocumented, a status that can make them vulnerable to threats and intimidation by supervisors.

In other industries, workers can form a union. In agriculture, it’s more difficult.

However, the New York Farm Bureau argues that if farmworkers had the right to collective bargaining, it would pose additional challenges for New York state agriculture, an industry that has suffered serious economic turmoil in recent years. According to the National Agricultural Statistics Service, farm income fell by $1 billion in 2015. And the years since haven’t been better. This downturn is due to several factors, the Farm Bureau says, including an increase in the state’s minimum wage, tax hikes and higher prices for animal feed, fuel and other supplies.

Organizing workers would create rules and regulations that would make it more difficult to do business, according to the Farm Bureau.

“Any kind of confining work agreements can be difficult for farms to deal with when uncertainty is so much a part of agriculture,” says Steve Ammerman, spokesman at the Farm Bureau, which lobbies state government for agricultural interests. “Whether it’s the weather, whether it’s commodity prices, whether it’s pest infestations, whether it’s a tractor that breaks down. There’s so much that happens on a farm that it can just make it that much more difficult.”

Ammerman says farmers shouldn’t be turned into villains.

“So much of the opposition … really likes to paint this really broad stroke of farmers as people who don’t care about their workers,” Ammerman says. “That is so upsetting for our farmers to hear …The stories I’ve heard of farmers who go above and beyond to help their farmworkers — that story just doesn’t get told.”

There are issues regarding farm labor on which the New York Farm Bureau and the workers’ rights organizations could agree Ammerman says — namely, immigration reform, human trafficking and having a day of rest.

New York state gives certain protections to farmworkers that are not guaranteed in other states: if a farm has more than 10 employees, it must provide unemployment insurance; and there’s workers’ compensation as well as disability coverage for injuries that occur off the job.

“Our farmers are passionate about their employees,” Ammerman says. “Why would a farmer go out of their way to mistreat the people they rely on so much to do such an important job?”

Yet, sometimes they do, and Hernandez says he was a victim of such mistreatment.

On a Saturday in February, Hernandez trekked across the parking lot of a mall in Syracuse where he had worked during its construction as a carpenter, laying the floors for one of the buildings. It was brutally cold — not like Mexico, Hernandez says — and dunes of snow lined the sides of the roads. He wore a puffy black coat with a fur-lined hood.

It was the first day of Winterfest in Syracuse, and the center of town had been converted into an ice rink. A small group of skaters waited for the Zamboni to finish its rotation. On the local news that night, the anchors expressed the community’s concerns that Winterfest attendance had been shrinking over the past few years.

Hernandez started working at Marks Farm in 2012, when he was a teenager. But before he left Mexico for the U.S., something happened that presaged his coming experience. Genaro, a man from a nearby town who had gone to work in dairy in New York, had been killed in an accident at work and his body was shipped back home. Hernandez hadn’t known Genaro, but once they heard of his death, his family feared for Hernandez’s safety.

“I didn’t know anything about working in agriculture, with cows in this country,” he says. “It’s not because I liked the work. It’s because I had a big responsibility and need to help my family economically. And I’m still helping them today.”

He departed despite their fears. From Mexico, he traveled to Lowville, New York, a small farming community along the Black River in the fertile North Country. He arrived at Marks Farm in April.

Marks Farm is family-owned, but it’s a large operation with about 9,000 cows and 60 workers. The farm’s website says, “total cow comfort is stressed.”

Hernandez worked 12 hours a day, from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., or beginning at 6 p.m. and lasting through the night until 6 a.m. Sometimes work was more important than lunch or a water break. But he was good at his job and the supervisors knew it, giving him work that was more complex and required more responsibility in the daily operations.

“There are a lot of cows,” Hernandez says. “There’s a lot of pressure in the work and it’s very intense … If you don’t attend to the cows, they’ll die.”

From the start, he says, he was given very little training to work with cows. In the autumn of 2012, a cow stepped on his hand, mangling his fingers. Hernandez says that he told the owner, and he thought she would take him to the hospital. She never did, and she didn’t tell him how to get there on his own. For months afterward, Hernandez felt excruciating pain when he ran his hand under hot water.

“When this happened, I didn’t know anything about my rights as a worker,” Hernandez says.

At the time, the worker housing was bad. Workers were crowded together in bug-infested housing with broken windows. Things improved in 2013, when other workers protested the conditions.

It wasn’t just the living conditions that were bad, Hernandez says.

The gloves and boots the farm gave to the workers were insufficient to protect them from the chemicals they worked with. If they wanted better ones, the workers would have to buy them from the farm out of their own salaries, Hernandez says. Over the course of the years that Hernandez worked there, iodine yellowed his fingernails and toenails, even though he wore three layers of gloves.

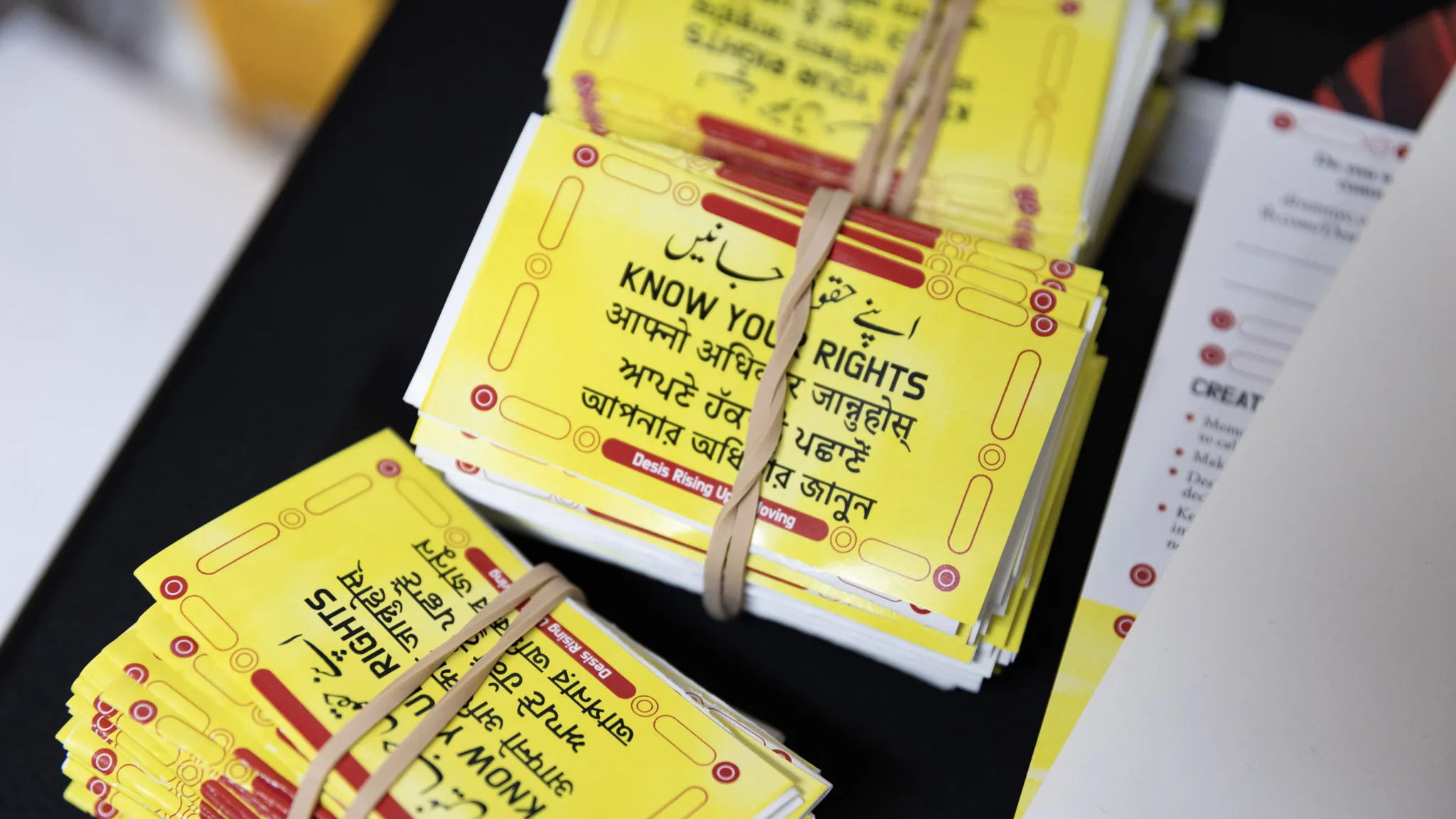

In 2014, jaded by his treatment at Marks Farm, Hernandez became a member of the Workers’ Center of Central New York, a nonprofit that provides farmworkers with information about their rights and benefits and does community service. Hernandez attended the monthly member meetings in Syracuse, an hour and a half away, if he didn’t have a shift scheduled.

The catalyst came in March 2015 when Hernandez’s coworker, Francisco, was allegedly “kicked in the head and beaten by Michael Tabolt, a supervisor on Marks Farm,” as reported by the Watertown Daily Times, a North Country newspaper.

On May 1, 2015, the May First Agricultural Workers’ Committee, the Workers’ Center of Central New York and the Worker Justice Center of New York held a rally at the farm to protest the mistreatment — a “historic event,” Hernandez says. But Hernandez didn’t attend. He was afraid of retribution and says that he knew being involved meant being fired from the farm.

That summer, things steadily became worse for Hernandez. He says as his supervisors became suspicious of his involvement with the Workers’ Center, he was demoted to being a relevo, a relief worker, assigned to odd jobs around the farm. He knew that the supervisors suspected him of being involved in organizing the protest and meeting with the Workers’ Center.

“What’s important to know,” Hernandez says, “is that these were all intimidation tactics.”

According to court documents, on an evening in late August 2015, Hernandez asked Rebecca Fuentes of the Workers’ Center to come and meet with him and a few other farmworkers. They discussed the inadequate gloves and the need to arrange English lessons for the workers. They signed up to become members of the Workers’ Center. ID photos were taken. Midway through the meeting, Christopher Peck, the son of the owners and a supervisor at the farm, banged on the door, telling Fuentes that he was going to call the police if she didn’t leave. She stayed.

Forty minutes later, Peck came back with two law enforcement officers. The police interrogated Fuentes about why she was at the trailer, if she had visited any others trailers, if she had visited the property before and if the workers had invited her. Fuentes told them that the workers had a right to have guests. One of the officers asked the workers if they wanted Fuentes to be there. They all responded that they did.

Peck wanted her arrested, but Fuentes told the officers that they didn’t have the authority. They left, one officer telling her that he would research the law in her case. Everyone was shaken, but the meeting continued. At the end, they made a plan for Fuentes to return on the last day of the month.

During the next week, Fuentes talked on the phone with Saul Pinto, Hernandez’s coworker, and he suggested that they go around to other trailers during the next week to raise awareness about the Worker’s Center. The other workers wouldn’t return Fuentes’ calls.

On Aug. 31, Fuentes returned, bringing another member and volunteer from the Worker’s Center for backup, as well as Carly Fox, a worker’s rights advocate from the Worker Justice Center of New York. The other farmworkers didn’t come back to the meeting, but the group, along with Hernandez and Pinto, went trailer to trailer, like they had discussed.

As the workers rang doorbells, Peck drove alongside them in his open-air four-wheeler, his German shepherd in the passenger seat. Hernandez says that Peck acted friendly, greeting them by saying, “hey guys,” before driving away.

The next day, Hernandez and Pinto were fired and given four days to leave. They were told that their final paychecks would be withheld until they signed a document written in English, saying that they were let go as part of a workforce reduction at the farm. Marks Farm had recently hired several new workers. Hernandez says he and Pinto knew there was no workforce reduction. Marks Farm didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

In the four days he was given to move out, Hernandez says he stayed in his trailer, his heart pounding uncontrollably. His family back home — his abuelitos, parents, and brothers — relied on his income for support. Now he was out of a job with nowhere to go. On the fourth day, representatives from the Workers’ Center and the Worker Justice Center helped Hernandez and Pinto move to housing that the Workers’ Center had set up.

Pinto has since been deported. Hernandez now works for the Workers’ Center of Central New York as an activist, teaching workers about their labor rights and lobbying politicians so that they’ll better understand the situation of agricultural workers. Over the years that he’s been gone, his brothers have had children he’s never met in person. They’re too young to know who he is.

The firing of Hernandez opened up a window for farmworkers’ rights organizations in New York to challenge the old laws that made it difficult for workers to bargain collectively. In 2016, the Workers’ Center, the Worker Justice Center and the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) sued the state of New York, saying the state law was unconstitutional.

It was the first lawsuit demanding that agricultural workers receive equal treatment but not the first time the issue had been brought to the attention of state lawmakers.

Farmworkers were “relatively defenseless and powerless,” said a task force commissioned 27 years ago by Gov. Mario Cuomo to examine the conditions of New York agricultural workers. He called for the government to “begin the slow and difficult process for redressing these inequities.”

But years passed and nothing ever happened.

In 2000, workers’ rights organizations drafted legislation called the Farmworker Fair Labor Practices Act, which would ensure, among other rights, collective bargaining without retaliation. It’s another dead end; the measure has been tied up in the Senate for 15 years.

Discouraged by one failed attempt after another, civil rights organizations in the state grasped Hernandez’s case as an opportunity to achieve equality for farmworkers. The NYCLU took Hernandez’s case.

“This is an issue that the NYCLU has been aware of for quite some time,” says Erin Beth Harrist, NYCLU senior staff attorney and lead counsel on the case. “It was percolating up to the level of it needing to be brought to court.”

When the litigation was filed against the state of New York, Gov. Andrew Cuomo and former state Attorney General Eric Schneiderman agreed with Crispin Hernandez and the NYCLU, saying that the state wouldn’t defend itself in the suit.

“It defies logic that the right to organize without retaliation would be afforded to virtually every worker in New York state, yet exclude farmworkers in a seemingly clear violation of our constitutional principles,” Cuomo said in a statement. “New York will fight this injustice and continue to ensure the rights and equal protections of all workers.”

Yet Harrist says that, on this issue, Cuomo has been all talk and no action.

“We would argue that if [Cuomo] has said it is unconstitutional, he should be doing more to make sure the legislature acts here, and I’m not seeing that,” Harrist says.

The attorney general’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

When the state decided not to argue against the case, the New York Farm Bureau stepped in with its yearly revenue of over $4 million and its own PAC. In October 2016, the state Supreme Court ruled that the Farm Bureau could intervene as a defendant in the case, picking up where the state had left off. Hernandez’s lawyers from the NYCLU didn’t object.

“This needs to be a battle that is finally said and done,” said Harrist.

The hearing was set for July 20, 2017.

The NYCLU argued that the state employment law violates Article 1, Section 17 of the state constitution, which guarantees workers the “right to organize and bargain collectively.” The original law, the New York State Employment Relations Act (SERA), was racist, the NYCLU argued.

SERA had been adopted in 1937 and was modeled off the 1935 National Labor Relations Act (also known as the Wagner Act), which was part of federal New Deal legislation. The NYCLU alleged that both the Wagner Act and SERA are racist, having been pushed through Congress by Southern Democrats who perpetuated discrimination in the largely nonwhite agricultural labor sector.

The Columbia Law School Human Rights Clinic and the Pacific Legal Foundation agreed, filing amicus curiae briefs in support of Hernandez and the NYCLU.

“Too many New Yorkers don’t realize that the food they eat and the profits for farms are made on the backs of farmworkers who are Mexican and Central American immigrants that are vulnerable to exploitation,” Carly Fox, senior rights advocate with the Worker Justice Center, said in her affidavit.

The industry doesn’t lend itself to unionization and set-in-stone regulations, the Farm Bureau responded. Agriculture, an industry affected by changing seasons and weather, is irregular. Collective bargaining wouldn’t account for “the unique challenges of farming, including the seasonal nature of farm labor and the perishability of crops,” the Farm Bureau said in its motion to dismiss Hernandez’s case.

Ultimately, McNally at the Albany Supreme Court dismissed the case on Jan. 3, stating that changes to state employment law must be made through the legislature and not the courts. McNally also wrote in his decision that the NYCLU failed to demonstrate that the labor laws were racist.

“Did you hear about the bad news?” Hernandez asked.

Hernandez was disappointed, but he and the NYCLU are prepared to fight it out with the Farm Bureau in court. The NYCLU filed a notice of appeal in February and submitted an appeals brief in June. The state of New York and the Farm Bureau will file their briefs this summer. Then a date will be set for an oral argument in the Third Department in Albany, the appellate division of the State Supreme Court.

“We will continue fighting for a victory,” Hernandez said in a statement. “With the help of God and all our supporters, we will change the conditions that we deal with as farmworkers, and we will keep pushing to be treated like human beings.

In person, Hernandez is less optimistic. He knows the case could go either way. His own future is similarly unclear — what’s the next step after starting as a dairy farmer and ending up as a labor activist?

“I don’t know my destiny,” Hernandez says.

CORRECTION: The second paragraph of this article was edited to reflect that the case was dismissed in January 2018, not July 2018, as it previously stated.