Jumaane Williams, a son of the post-1965 wave of migration that gave New York the largest West Indian population outside the Caribbean, enjoyed the support of his community in his race Thursday for the Democratic nomination for lieutenant governor.

He failed to defeat incumbent Lt. Gov. Kathy Hochul in what amounted to a bold challenge to her powerful running mate, Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

Williams dominated in Brooklyn and Manhattan, securing almost double the vote in the former and winning by a comfortable margin in the latter. This was despite being vastly outspent by the incumbent, and also running against Cuomo who secured a comfortable victory against Williams’ preferred running mate Cynthia Nixon.

The councilman was unable to secure the remainder of the city. Hochul landed 53.3 percent of the votes with 96 percent of precincts counted.

Williams was not the first Caribbean-American to run for a statewide office, but for many people, his candidacy represents another step in the political coming-of-age of one of New York’s major immigrant communities.

Williams’ parents, Gregory and Patricia Williams, were born in Grenada and came to the U.S. from the island in 1967. Both studied at Howard University. Williams was born in Manhattan in 1976 and raised in Brooklyn.

He became a City Council member in 2010 and has been a staunch advocate for the highly Caribbean-American community he represents in Council District 45, which covers Flatbush and Canarsie.

For a community numbered at some 906,753 people, according to NYCdata, Williams campaign signifies a new landmark for Caribbean-Americans.

“It’s very significant as a reflection of the powerful presence of Caribbean immigrants in New York City,” said Ron Howell, an author, English professor at Brooklyn College and former foreign correspondent in the Caribbean for Newsday. “I’m thinking back 20 years ago when Caribbean New Yorkers were struggling to have a presence in New York City politics.”

Howell wrote the recently published Boss of Black Brooklyn: The Life and Times of Bertram L. Baker, on his grandfather, who became the first black person to hold elected office in Brooklyn when he was voted into the Assembly in 1948. Baker was also an immigrant from the Caribbean. A handful of West Indian candidates were able to break through in politics in Harlem despite a relatively small number of West Indians who were in New York at the time, Howell explained.

Among those was Basil Paterson, a son of the smaller, early-20th-century Caribbean migration who became active in Harlem politics in the 1950s and whose son, David, was elected lieutenant governor in 2006. He later served as governor, filling out the term of Eliot Spitzer.

Following the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which ended immigration-admissions based on race and ethnicity, there has been a large increase in the number of Caribbean immigrants in the city.

Many of them reside in Williams’ Flatbush district. On Thursday morning, many of his constituents were eager to support the councilman’s bid to become lieutenant governor.

“He’s my boy,” said Harrison Delbert, a retired Flatbush resident. “I’m Jamaican. It means a lot,” Delbert added on the chance of having a Caribbean statewide elected official.

“Jumaane Williams nicely bridges the Afro-Caribbean and African-American communities,” said Dr. John Mollenkopf, director of the Center for Urban Research at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, where he studies the political integration of immigrants. A victory by Williams would’ve been a significant recognition for Caribbeans, he said, “a community that, all the islands

taken together, has historically been the largest immigrant group to New York City.”

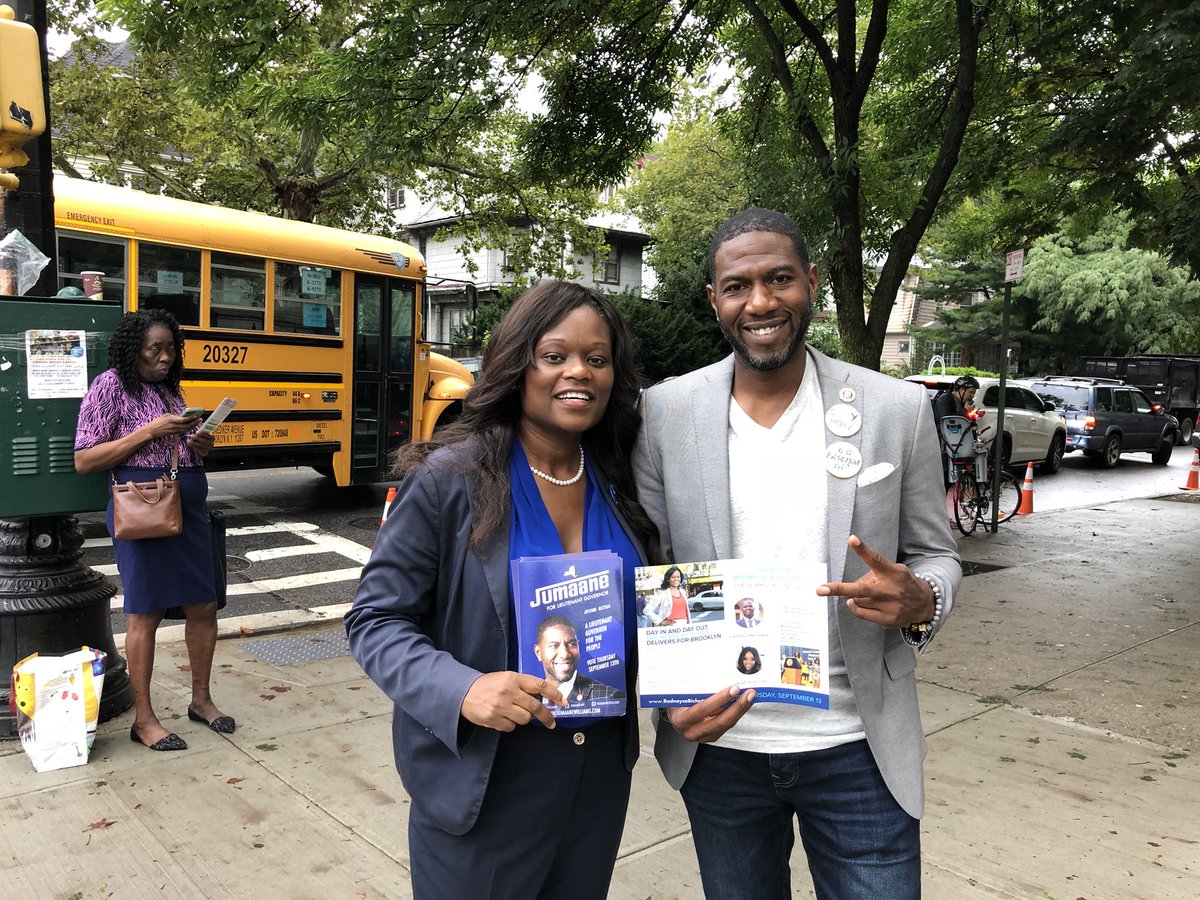

Also at the polls in Flatbush was Assemblymember Rodneyse Bichotte. A Haitian-American herself, Bichotte had just voted for Williams.

“It means a lot to have a black male. So, that’s just icing on the cake that he’s Grenadian,” she said. “He’s done a lot for the Haitian community here in this district – there’s a large Haitian community – and he’s been really proactive on making sure that we are not the forgotten people.”

After a failed attempt to become the City Council speaker, Williams set his sights on the lieutenant governor’s role. He was not shy about wanting to use the largely ceremonial position as a bully pulpit to advance his progressive views and critique the governor.

Williams prefers the title “activist-elected official” to politician and his actions match that, especially when it comes to advocacy for immigrants.

He was arrested earlier this year while protesting the arrest of immigrant rights activist Ravi Ragbir by Immigration and Customs Enforcement. He could’ve accepted a plea agreement with the Manhattan district attorney but chose to fight the case and used it to criticize President Donald Trump’s immigration policies. He was eventually convicted of blocking an ambulance during the protest but acquitted of two other charges.

In 2011, police handcuffed and detained him at the West Indian Day Parade for walking on a gated off sidewalk — an incident that resulted in reprimands for three officers he accused of having a racial bias.

In the City Council, he has been an outspoken advocate for police reform, helping usher in a bill that created an inspector general for the Police Department. He has also been outspoken on tenants’ rights issues (he was previously the executive director of New York State Tenants and Neighbors).

Williams has also worked closely with Caribbean community groups such as the Haitian-American Community Coalition. “He has really been helping us at so many levels,” said Dr. Andre K. Peck, the coalition’s executive director, citing Williams’ assistance in their health initiatives, ESL classes and on immigration issues.