David Chu was grateful for the turnout. Community meetings often draw only a handful of people, but on this particular rainy evening, lines stretched out the door at Yung Wing Elementary School in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Chu was among them.

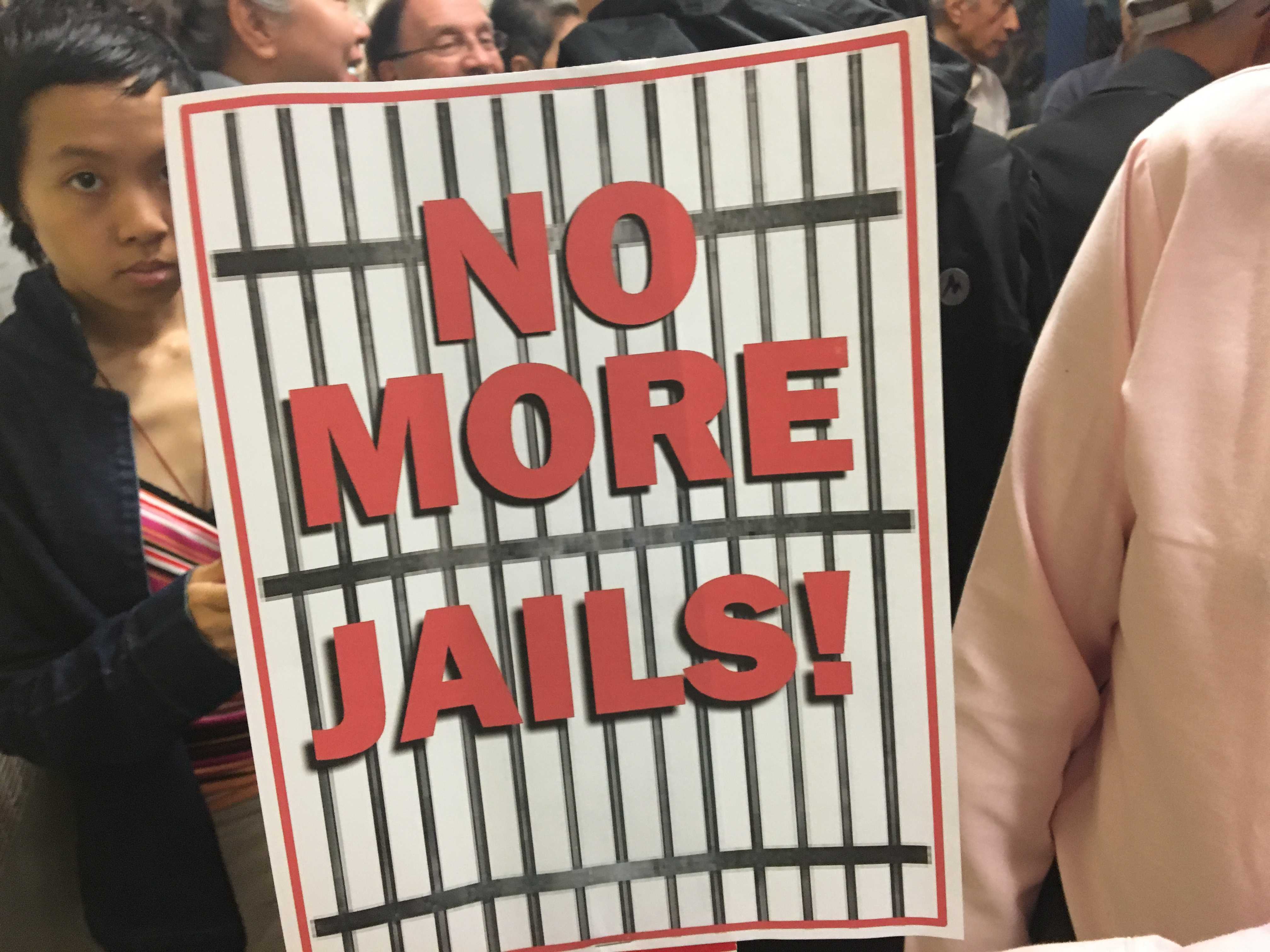

He had joined his neighbors to protest Chinatown’s selection as a location for a new “borough-based jail,” a keystone of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s plan to reform New York City’s criminal justice system. The city plans to close Rikers Island and rehouse detainees in four new jails, one in each borough except Staten Island. This $10 billion plan is meant to ease the travel difficulties and eliminate the “culture of violence” that have long plagued Rikers detainees and their families.

But when the city’s roadmap was released August 15, Chinatown residents were stunned. The Manhattan facility would not be a modification of the nearby Manhattan Detention Complex, as many expected. It would be a new, 40-story jail complete with ground-level retail at 80 Centre St., right on Chinatown’s southern boundary.

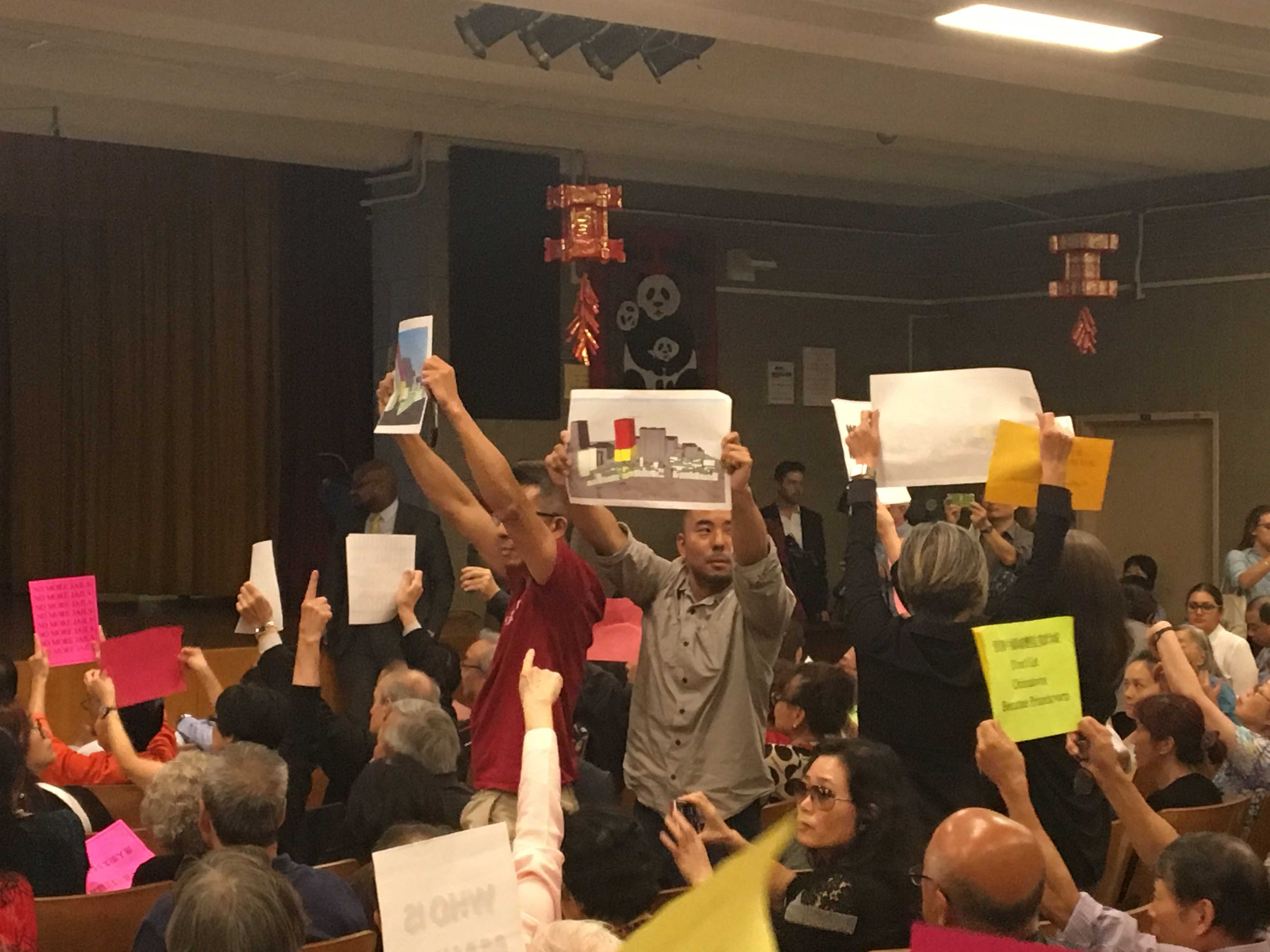

Chu and hundreds of Chinatown residents angrily voiced their disapproval of the city’s strategy at a September 12 hearing hosted by Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer and the district’s City Council member Margaret Chin. A packed house lobbed accusations of racism and classism at city staffers. They booed a slideshow so much the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice could barely finish. The long-awaited Rikers closure plan had run into Chinatown and unleashed the complicated politics of a largely immigrant neighborhood resentful about a legacy of neglect.

“Most of us think that they already have the thing decided,” said Chu. “All these gatherings are just window dressing.”

His resentment has deep roots. More than three decades ago, the city, under the Koch administration, expanded Chinatown’s current detention complex (known as “The Tombs”) with a nine-story tower. Thousands of Chinatown residents had marched on Centre St. The resistance and defeat over The Tombs are woven into the neighborhood’s history. The latest plan, said one resident, is “the same shit as 34 years ago.”

“They can’t fix the problems from the source, and we become the sink,” said Joe, a 50-year Chinatown resident who asked that his last name be withheld. “Let’s dump it in the South Bronx. Let’s dump it in Queens. Let’s dump it in Chinatown.”

The city, of course, refutes the complaints, and officials point out 80 Centre’s convenience to the courts and its modern jail design. That hasn’t quelled the belief among Chinatown residents that the city sees them as second-class citizens.

Chinatown gets ignored

Neighborhood anger over facilities traditionally associated with the criminal justice system is standard, from the reopening of the Brooklyn House of Detention to homeless shelters and reentry facilities. The complaints follow a similar track: The facilities will increase traffic. They will bring crime. No one was consulted. But wrapped up in Chinatown’s outrage is a pushback against the stereotyping of the community.

“I think it stems from the ‘model minority’ myth of seeing Asian Americans and particularly Asian immigrants as docile, as demure,” said Diane Wong, an assistant professor at New York University who has studied the gentrification of Chinatowns. “That stereotype and that trope has lasted through the decades.”

“Immigrants coming from mainland China never wanted to question the police or the government in case there was backlash,” said Nancy Kong, president of the board of directors at Chinatown’s Chatham Towers. “That gives way to the perception that the community is not involved or engaged.”

Three jam-packed meetings in Chinatown since the jail’s announcement have exposed that misperception. In fact, Chinatown has plenty of reasons to feel disenfranchised.

Park Row, a valuable connector for Chinatown, has been closed to public vehicle traffic since 9/11. Much of the parking annexed for post-9/11 security purposes has never returned. The city’s Environmental Assessment Statement for the proposed jail allocates 125 new parking spaces while also estimating an increase of more than 350 visitors a day to the facility. Even that, opponents say, is on the low side of what’s expected.

Chinatown’s health concerns also carry a unique urgency. City health data found that, as of 2014, Chinatown’s air had the city’s second highest rate of black carbon, a known carcinogen found in diesel exhaust. Of 190 city neighborhoods, Chinatown has the 11th highest rates of both nitric oxide and NO2, common emissions from construction equipment that are frequently associated with respiratory problems.

Numerous individuals, both at hearings and in interviews, expressed concerns about deteriorating housing options, a lack of senior living spaces, and a need for accessible social services. Many wondered why a large investment was being made in a jail while needed neighborhood resources are cut.

Indeed, 46% of Chinatown residents speak limited English and about 39% have not graduated high school, both double the citywide average. Nearly 30% of Chinatown residents over 65 live in poverty. Some 8% of Chinatown’s housing is considered “crowded”—residences that have more than one occupant per room — a rate more than three times the city average. And Chinatown experiences the city’s second highest rate of Hepatitis B, fifth highest rate of Hepatitis C, and eighth highest rate of tuberculosis.

A neighborhood of color

“I think it’s the same as many poor, working class neighborhoods of color in the city that have historically been disinvested,” said Wong, “in terms of resources, services, transportation, health access, housing, on all fronts. I think that’s why a lot of residents have these sentiments, that they’re angry and that they’ve been taken advantage of. Because of this history.”

The hearing September 12 did little to soothe the anger. Initially, the city publicly announced it would renovate MDC. On August 2, a closed-door meeting birthed news that two Manhattan sites were under consideration for a new facility. Less than two weeks later, the official Rikers plan was released. The city had chosen to build at 80 Centre St.

Since then, there’s been little clarification about whether the plan is a certainty. At an emergency hearing called shortly after the announcement, the mayor’s office called it a “done deal,” yet Margaret Chin’s office described it otherwise.

“It’s not a done deal,” said Chin’s spokesman. “It still needs City Council approval. Councilmember Chin needs a lot more information to get her support.”

“There is a process,” said David Burney, former Commissioner of the Department of Design & Development and a member of the borough jail implementation task force. “There are public hearings; there’s a statutory and environmental review process. Generally, the City Council follows the lead of the councilperson in whose district the project falls. So there’s a significant amount of leverage that communities have to discuss the project, modify the project, to get community benefits they feel are necessary.”

But Chinatown residents don’t trust this, given the way the plan was sprung on them. “For us to literally find out about this in August, with no options, has infuriated people,” said Kong.

While the city still needs to complete a full Scope of Work and the Unified Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP), speakers at the September 12 hearing said they didn’t trust the city to conduct fair studies. Several proposed an independent environmental assessment. Kong said she wants to “usurp the ULURP.”

“I want to challenge the Scope [of Work] and ULURP,” said Kong. “They want us to believe it’s a done deal so they can jump to talking about concessions,” such as offering to create various community facilities in exchange for Chinatown’s acceptance of the jail.

The jail brings crime

Some residents associate the location of a jail in their neighborhood with increased crime rates and argue that closing Rikers isn’t a solution to the overall problems with the criminal justice system. “Closing Rikers is not a solution,” said Joe. “The justice system is not working. It’s a contaminated petri dish. I don’t want a Kalief Browder in my neighborhood.” Browder hanged himself at age 22 after sustaining mental and physical abuse at Rikers.

Neighborhood concerns about crime, however, don’t bear out statistically. A recent City Limits analysis found no correlation between neighborhood crime and proximity to a correctional facility.

Kathy Morse, an activist who was detained on Rikers Island for 11 months, believes the city is partly to blame for this misconception.

“If [the residents] took a look at me they would never suspect that I was there, and I think that’s part of the problem,” said Morse. “I think that when they do these [hearings], they need to bring people who were formerly detained on Rikers to speak. They would realize, ‘You know what? They’re just like me. That could be my son or my daughter or my grandchild.’”

While residents maintained their objections aren’t based on race, Wong at NYU sees fears about increased crime as part of a conservative streak running through Chinese Americans, one that has helped mobilize them but might not be in the community’s best interest. She says that the community should begin thinking about alternatives to the carceral system.

“People used the word ‘criminal’ and I think that definitely speaks to how a lot of people are thinking about the prison system,” said Wong. “Where the conversation really needs to go is to think more about transformative justice and what abolition can look like. I think that is a conversation we need to bring back to our communities, and thinking about how—especially in a neighborhood like Manhattan’s Chinatown—we can have those conversations in a way that will be accessible.”

Future hearings are planned for each of the four sites, with the next in Chinatown scheduled for September 27. It remains to be seen what, if anything, can be done, though that hasn’t deterred residents from speaking out. Kong acknowledges that 80 Centre St. may end up as the final jail site.

“But I want to know why,” said Kong. “Not knowing breeds suspicions and assumptions.”