Nine-year-old Abigail Cruz stood in her sparkly high heels in nervous anticipation. Wearing a carefully ironed floral-print dress, she stood shoulder-to-shoulder with thirteen other girls in white silk sashes at the front of a large crowd at San Patricio Catholic Church.

Abigail’s mother, Blanca Villalobos, was also anxiously leaning forward in her front-row chair. That morning, Villalobos had carefully pinned back her daughter’s long brown hair with a pink rose, and now she smiled encouragingly to her soft-spoken daughter.

Cruz and her friends were representing the fourteen departments of El Salvador in the biggest event of the year at San Patricio. It was the annual celebration of El Salvador’s patron saint, which included this Miss Chiquitita beauty pageant. Stuffed tortillas called pupusas steamed on folding plastic tables set against the brick walls, and the grinding sound of ice beckoned children to the back of the room for some minuta — a Central-American version of a snow cone.

The pageant was not taking place in El Salvador, but in the basement of the church in Glen Cove, on Long Island. Abigail, like most of her friends, is a U.S. citizen, born on Long Island after her mother came to the U.S. 18 years ago. Her mother was allowed to stay under Temporary Protected Status, a special program enacted in 2001 after two devastating earthquakes struck El Salvador. The TPS program allowed any Salvadoran citizen already in the United States to live and work legally in the U.S. while their country recovered.

That program was designed to be temporary, but was renewed year after year — 17 years in a row. Its renewal led many of the 200,000 Salvadoran TPS recipients like Villalobos to have children, buy houses and start businesses in the U.S. Now, nearly 15,000 Salvadoran TPS holders reside on Long Island alone.

But those deep American roots could soon be torn up. On Jan. 8, the Trump administration announced the end of TPS for Salvadoran citizens, claiming El Salvador had fully recovered from the earthquakes. This decision was made even though the Salvadoran government is not prepared for the imminent return of TPS holders, according to the administration’s own documents. An influx of returning citizens could further destabilize the violent country and drive more illegal immigration back into the U.S. — factors that pushed prior administrations to renew TPS for so many additional years.

This time around, beneficiaries were told they must either apply for a different legal status or leave the country by Sept. 9, 2019. But many TPS recipients have little chance at obtaining legal permanent residency. Even if beneficiaries have adult children or spouses who are citizens, or jobs that could sponsor them, those who entered the country undocumented over 18 years ago — as many did during El Salvador’s civil war — could be denied.

Difficult choice

On Wednesday night, Judge Edward Chen of the Ninth Circuit issued a preliminary injunction on the end of TPS for El Salvador and three other countries – a temporary, but welcome, victory for families like the Villalobos. Yet even if Judge Chen ultimately rules on behalf of TPS holders, many obstacles lie ahead for those living on Long Island under the program.

The Trump administration did not consider the “full range of current country conditions” when issuing the TPS decision – a procedural change from past years, Chen wrote in a court filing. A permanent injunction would not necessarily prohibit the government from taking a second, more holistic look at El Salvador’s conditions and arriving at the same conclusion as before. The case could also go before the Supreme Court, where it would face a 5-4 conservative majority if Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination is confirmed.

In a worst case scenario for TPS holders, a decision for the government in the Ramos case would leave families right where they were before – a deportation order. The ultimate hope for beneficiaries still lies with two bills introduced in congress to address El Salvadorans’ residency issues, but they have stalled. With no clear solution on the horizon, families continue to face two stark choices. TPS holders can either leave their children behind in the U.S. and return to one of the most violent countries in the world, or disappear among the millions of undocumented immigrants living in America.

Local county executives advocating for TPS holders say a sudden deportation would be devastating to Long Island. A Suffolk County Department of Economic Development and Planning analysis showed a $1.4 billion reduction to the economy were the Salvadorans to leave. And for mothers with TPS, their worries are far more personal.

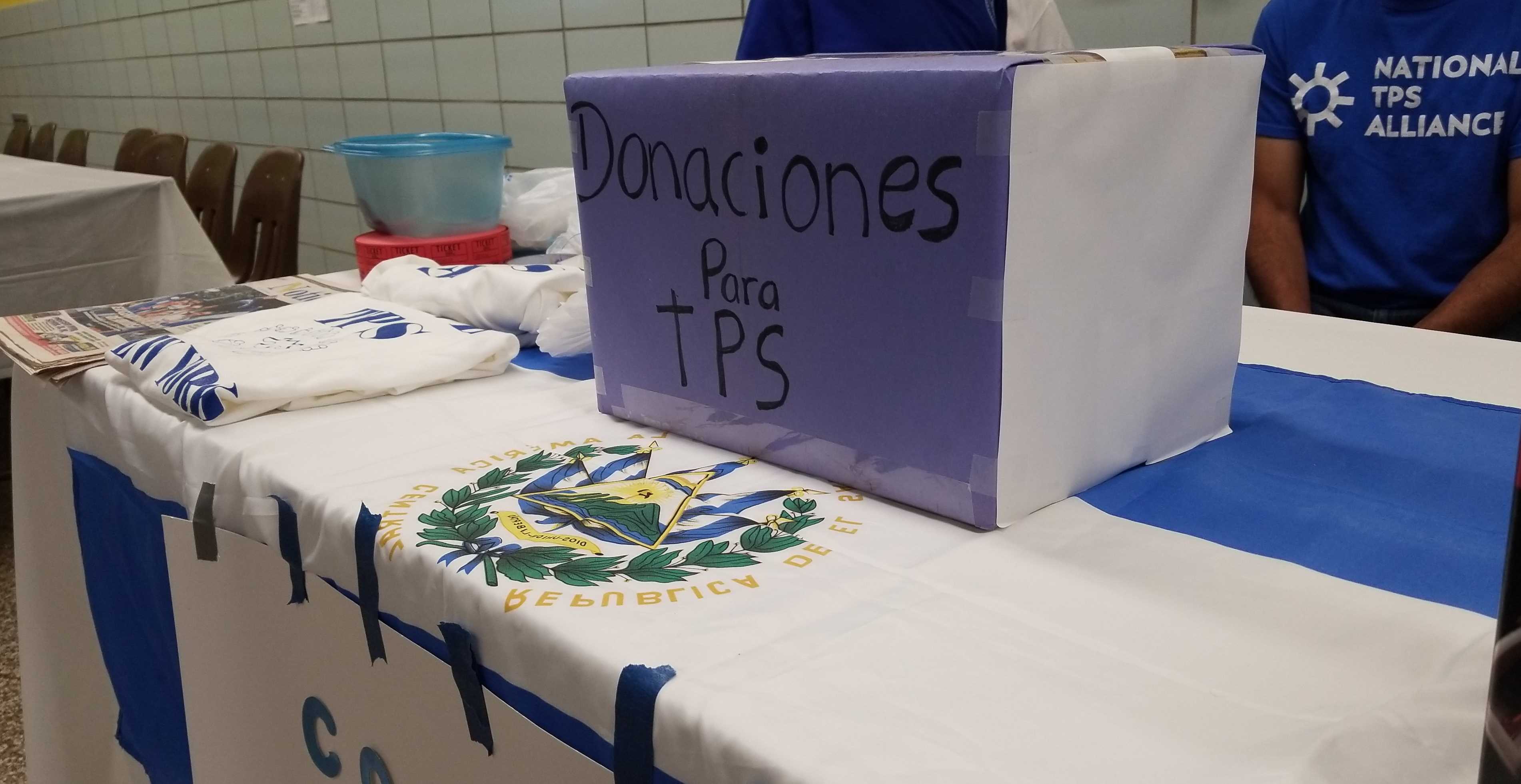

Across from the stage at San Patricio — St Patrick’s in English — a group of women manned a simple fold-out table. “Save TPS” was written in lettered stickers on an arts-and-crafts poster. The women could have been mistaken for the local PTA if they weren’t working to stop their families from being torn apart. As the crowd finished eating, two volunteers fanned out among the tables, selling raffle tickets in hopes of raising enough money to join the National TPS Alliance in a protest in Washington D.C. in November.

“It’s a $100 iron we’re raffling, have you bought tickets yet?” said Adela Rivas as she smiled, leaning over a family eating lunch off of paper plates. They reached for their wallets.

“Gracias!” she chimed.

Rivas — also a TPS recipient — chased down anyone who had not yet bought a ticket until her plastic bowl was full of bills.

Rivas works cleaning houses on Long Island, and keeps close with the local TPS committee. Now 41, she came to the United States when she was 17. She married another TPS recipient, has two young girls, age 7 and 12, and owns a house in Glen Cove.

“I’m afraid for my daughters,” she said, contemplating what might happen should she be forced to return to El Salvador. “I see the news and I think ‘My God.’”

Last year, El Salvador recorded 60 murders per 100,000 inhabitants, one of the highest murder rates in the world. Current data from the Salvadoran government shows so far this year, numbers are up even higher.

“If we just sit on our couch biting our nails, we’ll never achieve anything,” Rivas explained in lilting Spanish. “Better to fight for residency, for something positive.”

Hopefully, Rivas said, demonstrations and pressure on Congress will allow her family and others to remain in the U.S. as permanent residents.

Help from local officials

In the 17 years since they first arrived on Long Island, many TPS holders have become business owners and homeowners. And as they fight for their own rights, local government officials on Long Island have backed them up. In a letter to Congress, Nassau and Suffolk County Executives Steven Bellone and Laura Curran cited “a potential loss of nearly 13,500 jobs” if TPS holders leave. The officials then urged Congress “to support and champion a legislative solution to keep thousands of Long Island families and taxpayers here.”

Last year, the local Long Island TPS committee — called TPS Camino a la Residencia, which translates to TPS Road to Residency— joined with the National TPS Alliance to support two bills that would grant permanent residency for TPS holders. The SECURE Act is currently in the Senate Judiciary Committee, and the American Promise Act is now in the House. The National TPS Alliance hopes more supportive lawmakers will be elected in the U.S. midterm elections next month, and that there will be an even better chance at passing one of these bills.

Yet as TPS holders’ plight grows more urgent, other immigration crises and bills, principally one solidifying the status of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals recipients, are taking center stage. So to win time, El Salvadoran TPS holders are looking to the courts.

CASA de Maryland v Trump et al, filed in the U.S. Federal District Court in Maryland and argued in mid-September, claims the decision to end TPS for Salvadoran holders was made in a discriminatory manner. Ramos vs Nielsen et al., where the injunction was issued, focuses on U.S. citizen children of all TPS beneficiaries, no matter the country their parents came from. The American Civil Liberties Union and National Day Laborer Organizing Network, which filed the Ramos suit, claims the end of TPS violates children’s rights by forcing them to choose between their parents and their country of citizenship.

“[The lawsuit] is about children because we have many families where both parents are TPS beneficiaries,” said Evelyn Hernandez, executive committee member of the National TPS Alliance. “What will happen to these kids if their parents are deported?”

Still dangerous

Back at San Patricio, Elmira Valle contemplated what may happen to her 13-year-old daughter, Lisbeth Sanchez, if TPS ends. Lisbeth had recently offered her parents — both TPS holders — a shocking solution: She could just go into foster care.

“As a mother, I’m scared,” said Valle, glancing at a group of girls giggling in the corner. Valle had been appalled by allegations of abuse leveled at foster care agencies that took in children separated from their families at the U.S.-Mexico border.

“If it was just me, I wouldn’t care,” Valle said. But her daughter “is the only one I have.”

Daisy Flores, 30, also at the pageant in Glen Cove, is a DACA recipient, a grown daughter of TPS parents and a mother of three. In 2014, she left the U.S. to visit family in Santa Ana, El Salvador. But when she was about to return to the U.S., she realized her travel papers had expired. Flores suddenly found herself separated from her children and living the reality that many now fear, unsure if she would ever be able to come back.

“I felt terrible — there was so much insecurity,” Flores said. “My family told me not to even talk when I was in public. People will quickly hear an accent.” That indication could prove dangerous, she said, seeing as gang violence in El Salvador is especially prevalent against those perceived as outsiders.

Six nerve-wracking months later, Flores’ advance parole travel permission came through and she was able to rejoin her children on Long Island. But afterwards, some shocking news reached her from El Salvador.

“There was a boy I knew who lived next door,” she said. “They took him out of his house and killed him.”

Soon, the DJ at San Patricio called everyone’s attention to the front of the room. One by one, each Miss Chiquitita competitor paraded through two paper-mache palm trees until she reached the front of the stage. Finally, a girl in a long white dress — last year’s queen — walked down the aisle to hand over her crown to the next victor. It went to Abigail Cruz.

It was a bright moment in a dark time for both Abigail and her mother.

“Just the other day, she asked why they want to send us away if I’m not a bad person,” Villalobos later recounted. “She made me laugh when she said, ‘If immigration comes, I’ll chase them away, and I’ll never let them have you.’”

Before the TPS uncertainty, the Villalobos family was planning to buy a house. Now, they will have to wait. After all, there is a lot of uncertainty for Villalobos’ husband, who works as a driver in a landscaping business. What will happen if he loses his license? How will they even drive their kids to school? But one thing is for sure: They’re not taking their kids back to El Salvador.

“People were telling me to sign a power of attorney so that another person, a permanent resident, can take care of my children,” Villalobos said. “But I’m not going to do it … I feel like if I write that letter I’m giving up. I don’t want to give up. I want to keep fighting.”