On a recent sunny afternoon, Pablo chopped cantaloupes and coconuts on a folding table at his regular corner in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. His setup included huge jars filled with aguas frescas, a cutting board, bags of ice and big orange coolers resting on upside down milk crates. Originally from Mexico, he greeted customers in Spanish, while topping containers of fresh fruit with salt, chili powder and fresh squeezed lime, according to a customer’s preference.

Now 65, Pablo, not his real name, waved to friends and neighbors across the street and sprinkled “mi amor” into friendly banter with female customers. Regulars texted him in advance to order their drinks. Pablo has been selling fruit, juices, arroz con leche, and tamales on the street in Sunset Park for 13 years. He earns an average of about $80 a day.

Pablo is an undocumented immigrant, one of an estimated 560,000 living in New York City, according to the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs. He’s also one of the estimated 12.2% of undocumented immigrants who run their own business, according to 2016 data from New American Economy, a bipartisan organization that supports immigration reform.

In New York City, undocumented entrepreneurs have launched businesses from street vending to tech startups. They can, and often do, pay federal income taxes through an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN), which doesn’t require a social security number and they can open bank accounts. Some of the immigrants in this story are not identified by their real names.

Working off the books

Pablo came to the U.S. in 1997 after paying a smuggler $3,000 to help him cross the U.S.’s southern border. “It was difficult,” he recalled. “There was no water.” He made the five-day trip to seek better economic opportunities, settling in New York City where his nieces lived. Aside from a single trip to Mexico, he has remained in the U.S. without papers.

At first, he worked off the books at a horse stable, wiring money home to his family in Mexico, where he has five children. He said he now has an additional four children in the U.S. Unconcerned about deportation, Pablo said he just never got around to investigating how to get legal status. He could probably find a job off the books, but prefers working for himself. “There’s no one telling me what to do,” he said.

Charlie, not his real name, arrived in the U.S. as a six-year-old with his family and grew up in New York City. With his slight city accent, he sounds like any American-born 30-something entrepreneur, except for his legal status. The consultancy firm he founded in 2013 specializes in career development and college success, geared for students from underserved communities, often the first in their families to attend college.

Charlie didn’t intend to become an entrepreneur, he initially wanted to be a chemical engineer and later a university professor, but realized his status made those professions impossible. Generous scholarships and fellowships had been rescinded because he didn’t have a green card and after Charlie earned a master’s in criminal justice at City College, he realized getting hired legally wasn’t possible. Because of age requirements, Charlie failed to qualify for the Obama era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program launched in 2012 that allowed undocumented immigrants who arrived as children to work legally.

With few other options, Charlie became an entrepreneur. “I found it really weird,” Charlie said. “So, I can’t work for someone, but I can start my own business?” His frustration in finding a legitimate job inspired his business. “If you are going to block me from opportunity because of a broken immigration policy,” he said, “then I will do whatever I can so that promising, but under-resourced or untapped potential youth, will never feel like I did.” Revenue of his business has steadily grown since 2014.

Easier for Dreamers

While some undocumented workers start businesses because they can’t get legal employment, others who are DACA recipients, or “Dreamers,” can be employed legally but choose entrepreneurship for the same reasons any entrepreneur does.

Victor Santos, originally from Brazil, was inspired by Muhammad Yunus’s pioneering microfinance operation, Grameen Bank. He co-founded Airfox, where he’s the CEO. Santos, 27, calls Airfox “the bank for the poor 2.0” and sees it as a continuation of microfinancing using today’s technology: AI for credit scoring, blockchain for raising capital and mobile to access users. Airfox rolled out its first phase in Brazil with $100 loans.

Santos arrived in the U.S. as a 12-year-old with his parents on L-1 and L-2 visas. His parents wanted the family to have business and education opportunities not available in Brazil. But when they applied for a green card after living in California for years, they were denied. Santos attended the University of California, Berkley, where he earned a degree in business and engineering.

Because Santos is a DACA recipient, he was legally employed at Google and could have kept working there as a product marketing manager. Instead, he launched Airfox. Santos moved from the Bay Area in 2016 to Boston, where Airfox is now based, to participate in the Techstars Boston startup accelerator program.

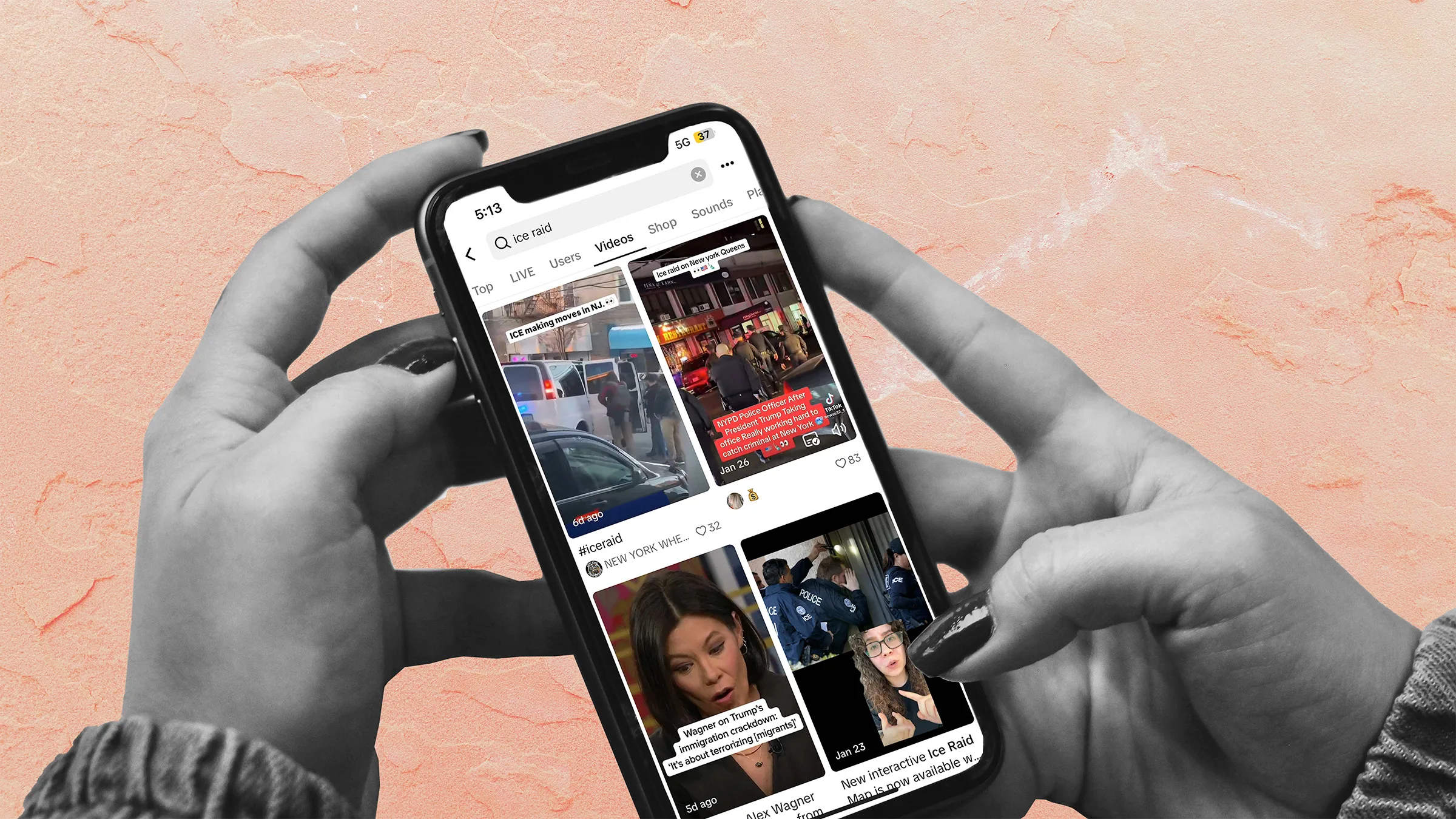

Until this year, Santos didn’t discuss his status publicly. If DACA ends or Santos loses renewal of his DACA status, he plans to return to Brazil, where Airfox already has an office. His 20 Boston employees would lose their jobs and the city would lose tax dollars. “I think it’s a zero-sum game for everyone,” said Santos.

Originally from Peru, entrepreneur Angel Reyes Rivas, 28, is also a DACA recipient. He co-founded a company just outside New York City that helps businesses and institutions with their mobile devices; he estimates its annual gross revenue at $150,000 to $200,000.

He arrived when he was 15 years old, but his mother was deported when he was a junior in high school and his brother followed soon after. Rivas continues to wire them money.

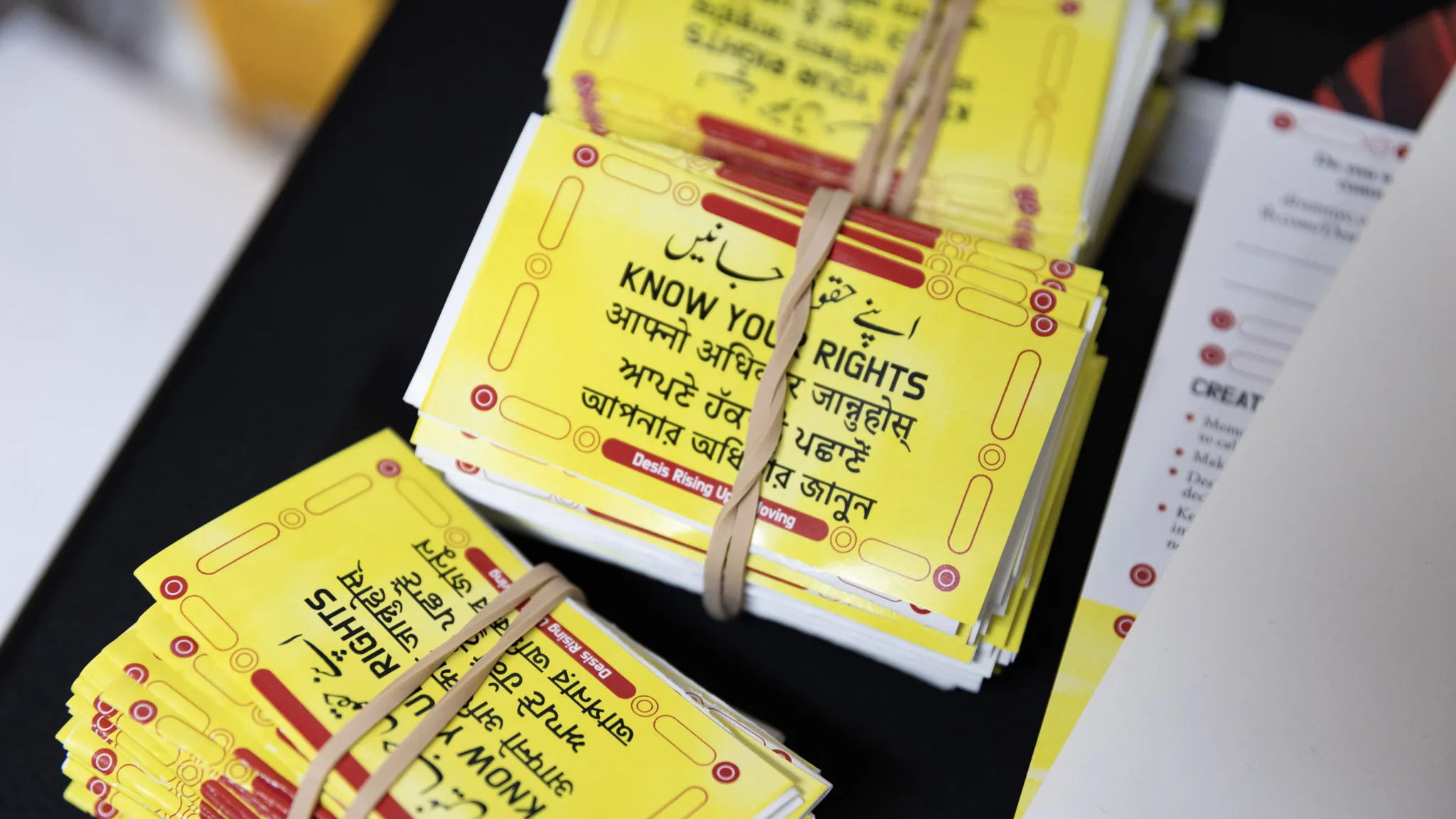

While there aren’t any official agencies dedicated to helping undocumented immigrants establish companies, many New York City agencies and organizations help entrepreneurs, regardless of status, with marketing, financing, social media, pitching, commercial leases, among other business issues. They include: Small Business Services (SBS), Queens Economic Development Corporation (QEDC), the Business Center for New Americans (BCNA) and Brooklyn Legal Services Corporation A (Brooklyn A), as well as numerous accelerators and incubators.

Options for undocumented entrepreneurs to obtain legal working status via visas or green cards already living in the U.S. are limited. Many successful tech entrepreneurs like Santos, Rivas and Charlie would most likely qualify for the “extraordinary ability” O-1 visa, or possibly the H1-B, or E-2, among other work-based visas, however, applying for one typically requires returning to an entrepreneur’s country of origin. They might be barred from reentering the US. “It’s risky,” said immigration lawyer Nadia Zaidi, based in New York City, of an undocumented entrepreneur leaving the U.S., “absolutely.”

Meah Clay, the Director of Brooklyn A’s Community and Economic Development Program (CED), advised that any undocumented person who wants to launch a business, should first talk to an attorney. Pro bono services, such as Brooklyn A, can help. An attorney can advise on a business structure and an emergency deportation plan.

Rivas has a verbal agreement with his partners should he get deported if DACA is terminated. “If that were to happen,” sighed Rivas, “I have talked with my partners; they are fully committed to supporting me. Financially, I wouldn’t be affected.” Charlie’s only deportation plan is to “make and save as much money as I can,” he wrote in an email. Meanwhile, Pablo in Sunset Park, has no emergency business plan should he get deported. “I work alone,” he shrugged.