The skinny 18-year-old Honduran sat off to the right side of the immigration courtroom, shackled at the hands and waist and alone except for the interpreter translating the proceedings to him.

The court documentation indicated that the teenager had agreed to be deported after illegally crossing the southern U.S. border, but the judge appeared worried that he had not spoken with an attorney and might not understand his options. He asked the detainee to raise his right hand and swear to tell the truth, then peppered him with questions: “Are you afraid to return to your country for any reason?”

“No,” the teen responded. Do you have family members in the United States? Do they have some claim to legal status? Yes and no, the teen responded. Eventually, the judge determined that there was no legal way he could remain in the U.S., so he wished the teen luck and ordered him deported. It was the detainee’s first hearing before a judge; he never did see a lawyer.

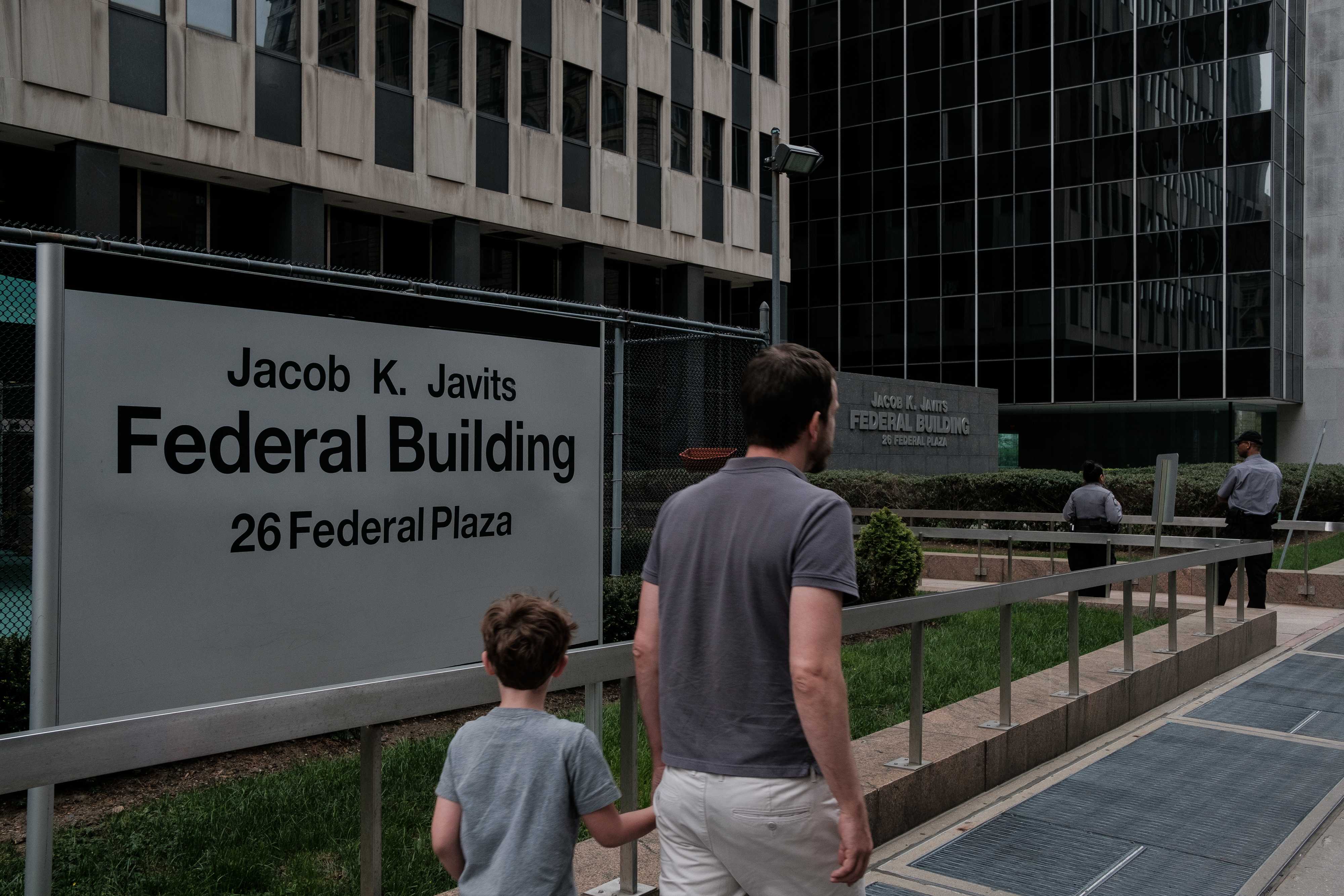

Scenes like this play out routinely in immigration courtrooms throughout the country. They are not supposed to happen in New York City, where the City Council created a public defender program for ICE detainees, the New York Immigrant Family Unity Project (NYIFUP). The project is supposed to provide a free attorney for any immigrant detained in the city, or whose case is heard in a city courtroom. Yet the situation above played out at an Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) courtroom in the federal facility at 26 Federal Plaza, in the heart of downtown Manhattan, less than half a mile from City Hall. The Honduran teenager wasn’t the only detainee last week to appear without counsel.

ICE suddenly docketed dozens of cases

Over three days in the week leading up to Christmas, ICE and EOIR—which is part of the Department of Justice—took the unusual step of docketing dozens of detained immigrant cases at 26 Federal Plaza, which usually only hosts non-detained cases. An area of the 12th floor was cordoned off from the public and guarded by the facility’s standard private security and agents from ICE’s Special Response Team (SRT) in green fatigues, as orange-jumpsuited detainees were shuffled in and out.

The three NYIFUP providers—Brooklyn Defender Services, the Bronx Defenders and the Legal Aid Society—were apparently surprised by the eleventh-hour docket announcement, and were unable to rustle up attorneys for all of the detainees at 26 Federal Plaza. Most detainees appeared to have been brought in from the Bergen County Jail in Hackensack, New Jersey, which is under contract with ICE to provide detention space.

Immigration court proceedings are open to the public, but judges can limit entry based upon a variety of factors including protecting witnesses and preserving order. When a reporter arrived at the entrance to the hastily-arranged secure area on Thursday morning, he was waved through after stating where he was going. When he returned for the afternoon docket, however, ICE SRT agents were blocking everyone who wasn’t an attorney or a family member of a detainee from entering the detained docket courtrooms. After the reporter reminded the agents that it was the judge, not them, who could limit courtroom access, they said the judge had decided to block observers from entering, then admitted that they had not spoken to the judge. After some discussion, the judge permitted the reporter and two legal observers to enter.

How many detainees did not have counsel?

Documented couldn’t determine how many detainees did not have counsel during the 26 Federal Plaza hearings scheduled for the Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday before Christmas. Documented witnessed four hearings involving detainees with no legal representation on Thursday, and Melody Godbolt, an attorney from Debevoise & Plimpton LLP working pro bono with NYIFUP, said she had witnessed others. ICE personnel prevented her from distributing materials informing detainees of services available, but immigration judges Charles Conroy and Donald Thompson did tell detainees they could access free legal services and reschedule their hearings.

Of the four hearings with unrepresented detainees that Documented observed, two, including that of the Honduran teenager, involved recent arrivals who had been caught shortly after illegally crossing the border. Two others involved longtime undocumented residents who had come to ICE’s attention after having contact with the criminal justice system.

A Guatemalan man who had resided continuously in the country since 1995 and was married to a U.S. citizen had been put in removal proceedings after serving time for a criminal conviction. His conviction prevented him from receiving legal status or cancellation of removal, Judge Thompson said. He advised him that he could seek voluntary departure, a form of removal that doesn’t count as a deportation and avoids triggering the ten-year ban on re-entry that affects deported immigrants who have been in the country unlawfully for one year or longer.

The man indicated that he was interested in seeking voluntary departure, but then seemed confused about the documents he was told he would need to make his case. “Do you not have anyone on the outside who could help?” Thompson asked, and offered to schedule a hearing for a few weeks later to allow him more time to gather evidence. But the man looked exasperated and told him he preferred to just be deported.

ICE representatives did not respond to questions about why detainees had suddenly had hearings scheduled in 26 Federal Plaza or if the practice would continue. Though NYIFUP seeks to guarantee an attorney for every detained immigrant, ICE is under no legal obligation to facilitate the program because it is administered by the city. NYIFUP providers declined to comment.

“As an Administration, we want to ensure that detained, unrepresented immigrants have access to immigration legal help through the New York Immigrant Family Unity Project. We have been in contact with legal service providers and the Immigration Court about this issue and will continue to monitor closely,” said Matt Dhaiti, press secretary for the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs, in a statement.

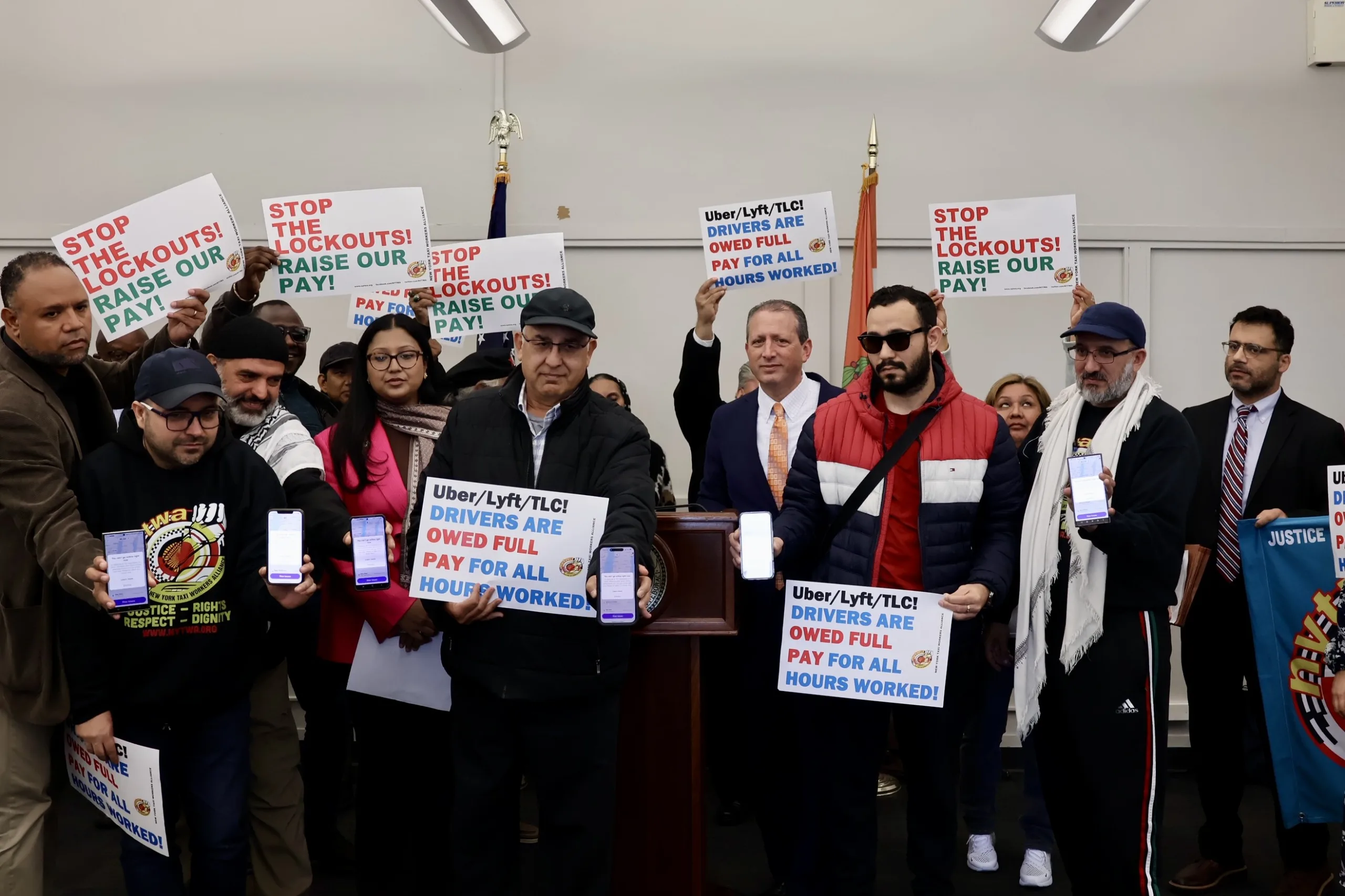

ICE faces a lawsuit filed by legal groups including the Bronx Defenders, one of the NYIFUP providers, which alleges that the agency has been violating detained immigrants’ due process rights by making them wait for months before their first hearings before an immigration judge.