Francisco Guzman heard about Thomas Hecht and his law firm at a soccer game one day in Staten Island’s New Dorp Park. Hecht, a friend said, could help Guzman get a coveted green card.

So in late 2015, Guzman went to see Hecht at his Times Square law office. Guzman had been in New York since July 1991, when he was just 21, had never left and had never gained documented status. At the Times Square office, Guzman was greeted by Thomas’ son, Leonard, who spoke to him in Spanish. They went over Guzman’s case: how many years he had been in the U.S.; did he pay taxes; did he have a criminal record. Hecht said that based off his answers, he could get Guzman a visa. Guzman left the office and walked past a crowded waiting room.

Months before, he had met with another immigration lawyer. In that intake interview the attorney asked Guzman his country of origin. “I said I was Mexican. He said there’s really nothing we could do at that moment.” But the lawyer did offer to submit an asylum application on Guzman’s behalf as a way to buy time. “In a period of one to two years, the asylum case would be denied,” he told Guzman. After the case was denied, the lawyer would start fighting it. “When he mentioned the word ‘asylum’… I left, because I was not going to pursue it like that,” Guzman said.

Filing asylum claims long after arriving in the U.S. is a dicey move for most undocumented immigrants because it can put them on track to deportation. Unscrupulous immigration attorneys sometimes file asylum claims, which are mostly denied by USCIS, explained Carmen Maria Rey, a former immigration attorney and current professor at Brooklyn Law School.

The move is risky because the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services mandates that asylum claims be filed within a year of the person arriving to the U.S. If the claim is denied—likely if it’s past the one year mark—the immigrant’s case shifts to the immigration courts, run by the U.S. Justice Department, where immigrants have to defend their right to stay in the country against an Immigration and Customs Enforcement attorney. In court, they can request asylum again or a cancellation of their removal order as a defense against deportation. Lawyers will often delay the case as long as possible to allow their clients to remain in the country legally.

Taking a chance with asylum claims

Many immigrants whose attorneys file asylum claims aren’t aware of what the lawyers are doing, said Maria Rey. “They didn’t realize they were taking a chance,” she said, adding that they would be ordered deported when they went in front of a judge.

Guzman left the first meeting with Hecht with a list of things he needed to bring to support his application. He went back again, and answered several of the same questions. The third meeting, he brought all the information and paid part of a total of about $8,500 in legal fees. “After I gave my payment to start the case, without my consent or knowledge, I found out he submitted an asylum application on my behalf,” which was exactly what Guzman did not want.

Guzman is now one plaintiff in a lawsuit filed by the immigrant advocacy organization Make the Road New York against Thomas Hecht and Leonard Hecht. Leonard Hecht and his father, Thomas, both graduated from Brooklyn Law School. According to their website, in addition to immigration law, the firm practices real estate, divorce, wills, commerce and trade, particularly with Cuba. Thomas has been a lawyer since 1957, according to the firm’s website. Leonard speaks Spanish has been a lawyer since 1988, according to the site. He has written for Crain’s and the New York Law Journal. Thomas Hecht and Leonard Hecht are the only listed attorneys working at the firm.

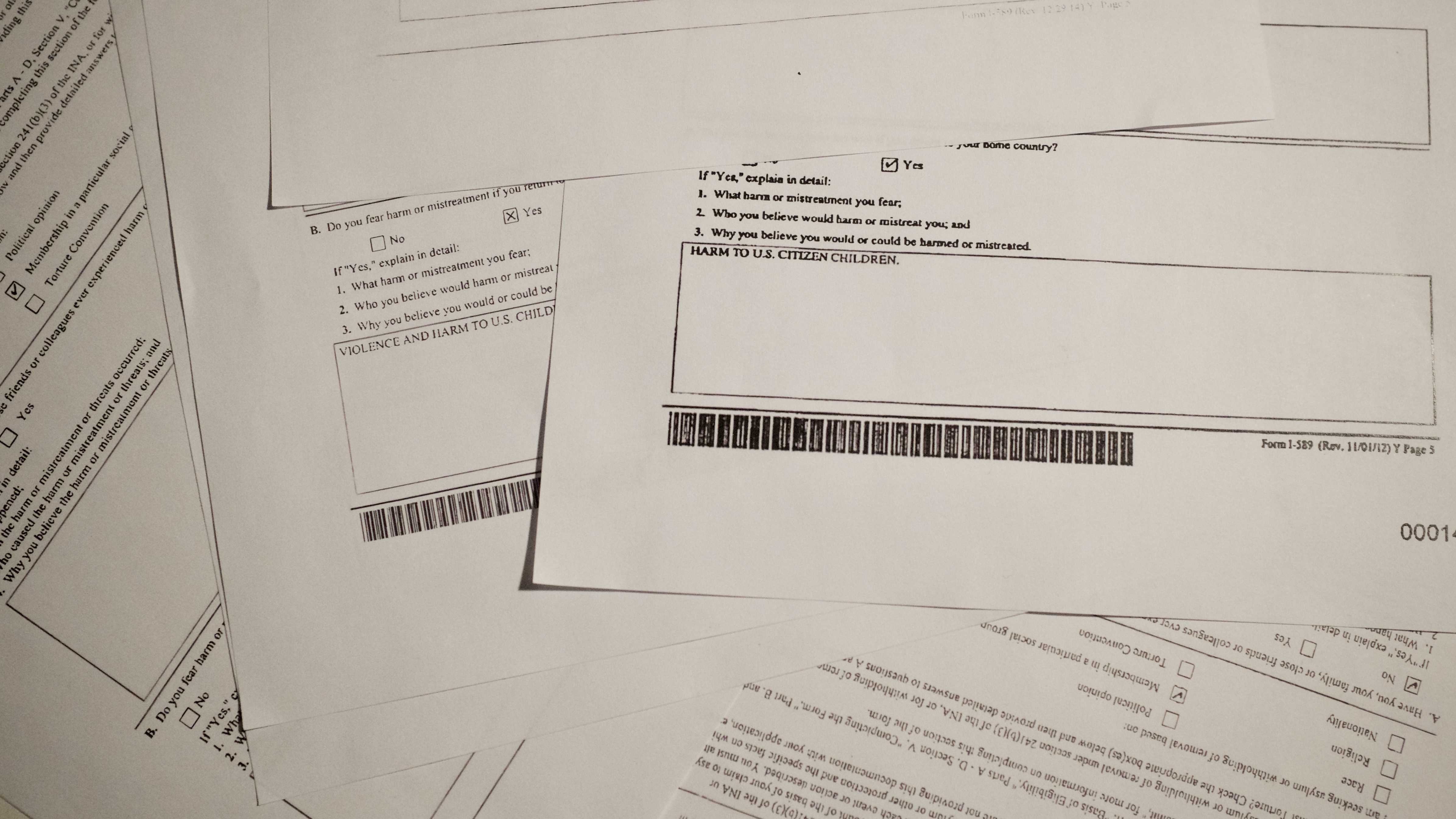

Make the Road provided Documented with six asylum applications filed by the firm. Five of the applications include the same one sentence description of why the applicants fear returning to their home country: “HARM TO U.S. CITIZEN CHILDREN.” The other application read “VIOLENCE AND HARM TO U.S. CHILDREN.”

According to the lawsuit filed in the Southern District of New York federal court, Hecht and his son, “used their positions to take advantage of Plaintiffs’ inexperience, lack of legal expertise, limited formal education, and limited ability to read English in order to financially profit.” The plaintiffs claim that the Hechts deceived their clients into believing there’s a path to legal residency available to people who have lived in the U.S. for 10 years or longer, which doesn’t exist.

Instead, the Hechts filed asylum applications on their behalf which often were denied and put them at risk of deportation, the suit said. Leonard Hecht told the New York Times last May that the firm had not done anything fraudulent. No one from the firm responded to a request for comment at the time of publication.

Maria Rey said tricking immigrants into filing asylum claims was a common tactic. While working at Sanctuary for Families, a nonprofit legal advocacy organization that works with defendants in the City’s human trafficking court, she observed how human traffickers would enlist people in New York to file false asylum claims for women they had brought to the City for sex work.

False application becomes court record

“A lot of those individuals have valid asylum claims,” she explained. The person filing the reports will often use a very basic or fictitious explanation of the danger that asylum applicant is facing in their home country. The false application becomes court record, which in itself is not enough to endanger the applicants status in the U.S. The live testimony before USCIS is where it becomes dangerous for the asylum seekers, Maria Rey said.

“Lying in person, that could be enough to bar you from the United States,” she said.

After Guzman learned the firm had submitted an application for asylum on his behalf he went to to Hecht’s office. He showed the asylum claim receipt to an assistant at the firm who told him not to worry because “that’s how he starts his cases.” He came back eight days later and found Leonard Hecht. “He said do not worry, things are a little bit complicated with President Trump. When I asked him why he submitted an asylum application without my consent, he didn’t reply, he didn’t give me an answer.”

Guzman began seeking consultations to better understand what was happening. He is now represented by another attorney and they’re trying fight his immigration case in the asylum office and immigration court. Recently, Guzman got an invitation to testify in front of an asylum officer.

Some visas exist for immigrants who are victims of crimes, but they are largely granted to people who help in police investigations. Currently, people like Guzman have little clear recourse against the attorneys who put them on track to deportation.

“All I can say for now is I’m very confused and there’s a lot of uncertainty about what’s going to happen. Most of these days I’m anxious about what can happen,” he said. “A couple of days ago I was admitted to the E.R. because I think I had an anxiety attack.”

Guzman has two daughters who are both U.S. citizens. He works for a carwash company and moving cars. If he does get ordered removed, he is at a loss for how to prepare for that potential stage in his life.

“I would want to prepare myself, but I honestly don’t know how,” he said. “With my age going back there, there’s really nothing for me.”