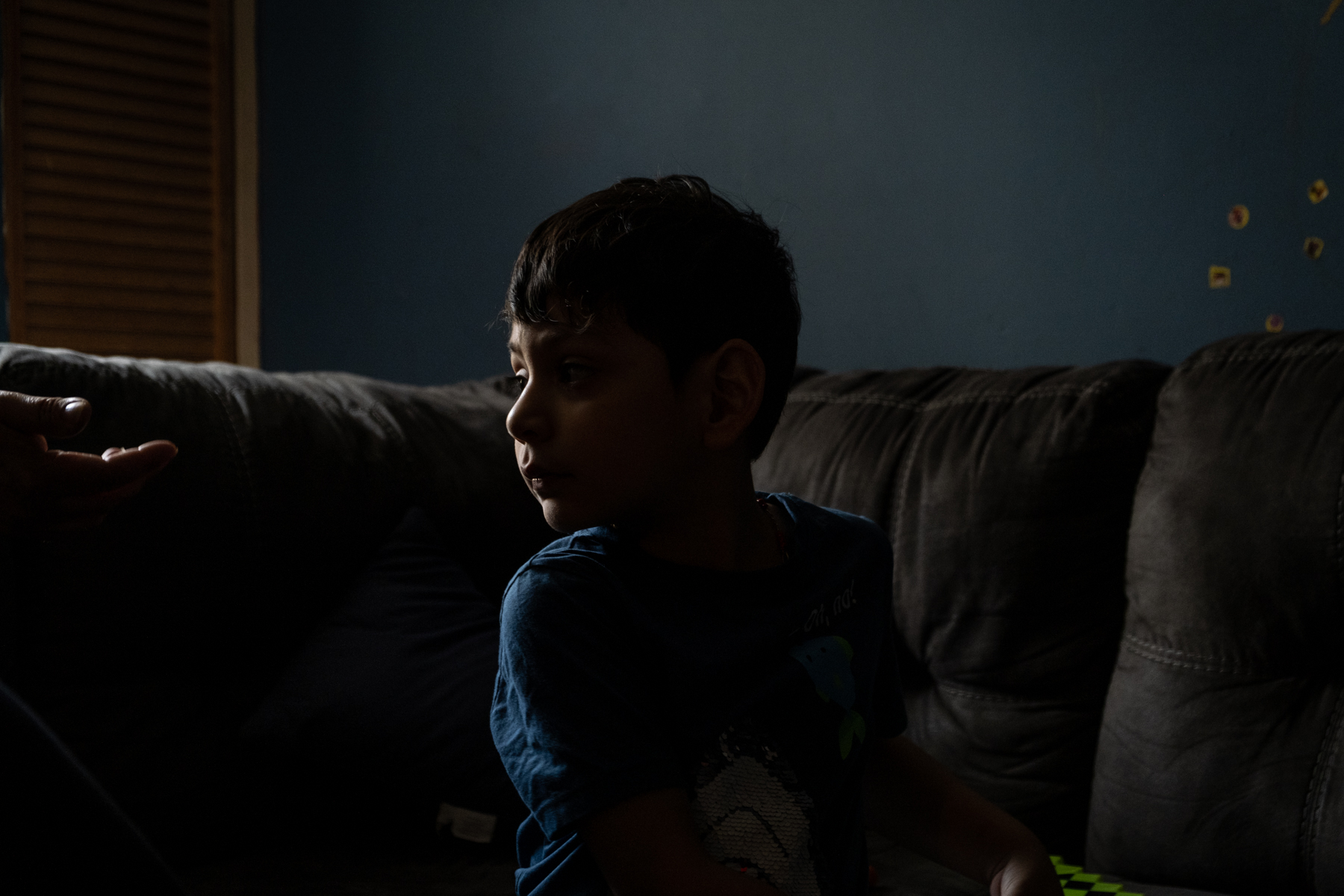

There was a time when 20-year-old Diego, a native of El Salvador, wasn’t sure he’d finish high school, much less go to college.

His father had abandoned his family, and his mother immigrated to Long Island so that she could make enough money to send back home and provide for him. Four years ago, however, the street gangs that controlled the neighborhood where Diego lived with his grandmother demanded that he join them, or die. His mother sent $7,000 to a smuggler to bring Diego to the United States, and sought special legal status that is provided to juveniles for whom it would be too dangerous to return to their home countries. The Trump administration, in an effort to crack down on the growing waves of unaccompanied minors that are flowing into the country, rejected Diego’s application.

He was one of an estimated 3,000 young immigrants in New York who were affected when the administration, without warning, changed the way it processed requests for what is known as Special Immigrant Juvenile Status, or SIJS. The new rules essentially denied status to applicants over the age of 18. Meanwhile the previous rules set the age limit at 21.

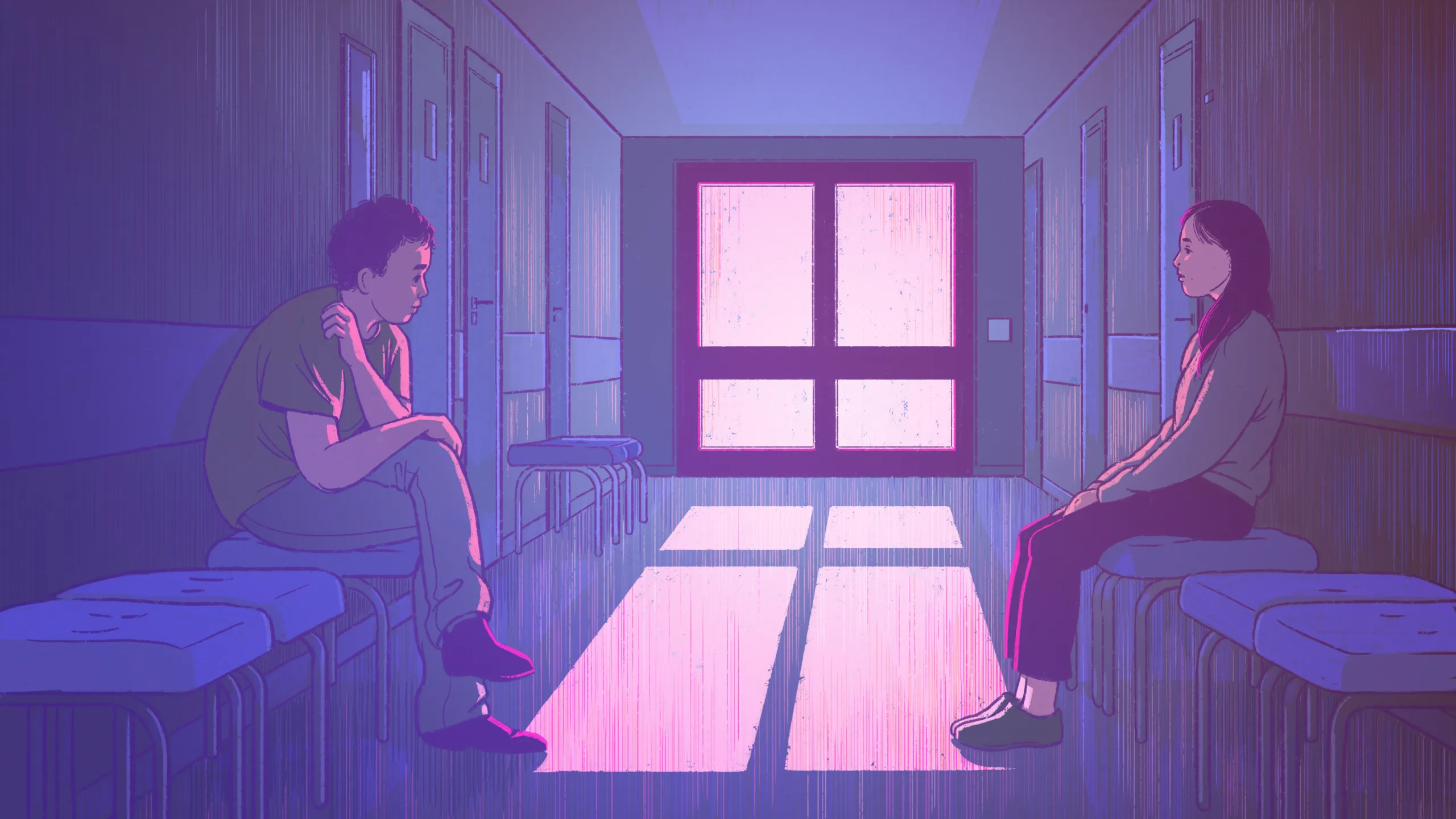

On March 15th, however, a federal judge in New York ruled that immigration authorities had violated the law by denying the applications. The judge then ordered the administration to reprocess them under the previous guidelines. Meanwhile, immigrants like Diego, a plaintiff in the lawsuit, are waiting to see if they can move on with their lives.

But Vanessa Caicedo, Diego’s attorney, worries that the administration, which sees SIJS as a gateway for gang members to gain legal status, will not comply with the order.

“In the climate that we have now,” Caicedo said, “it’s definitely wait and see.”

The start of a legal battle

Theodor Liebmann, an attorney and law professor at Hofstra University, agreed that getting the Trump administration to follow the order will be a battle. He said the judge’s instructions to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), requiring them to reprocess the SIJS applications that had been denied, potentially gave authorities a “second bite of the apple for finding other reasons to reject those applications.”

Diego says it’s hard to be patient. While he awaits a decision on his status, he can’t legally drive and work, or get health insurance or student loans. “I’m practically an adult and I have no way to sustain myself,” said Diego, who speaks haltingly to carefully choose his words. He asked to be identified by his first name only because his legal status remained uncertain.

“I’m scared and sad at the same time. Everything that I had to go through in my journey through Guatemala and Mexico to get to the United States, it might all be in vain.”

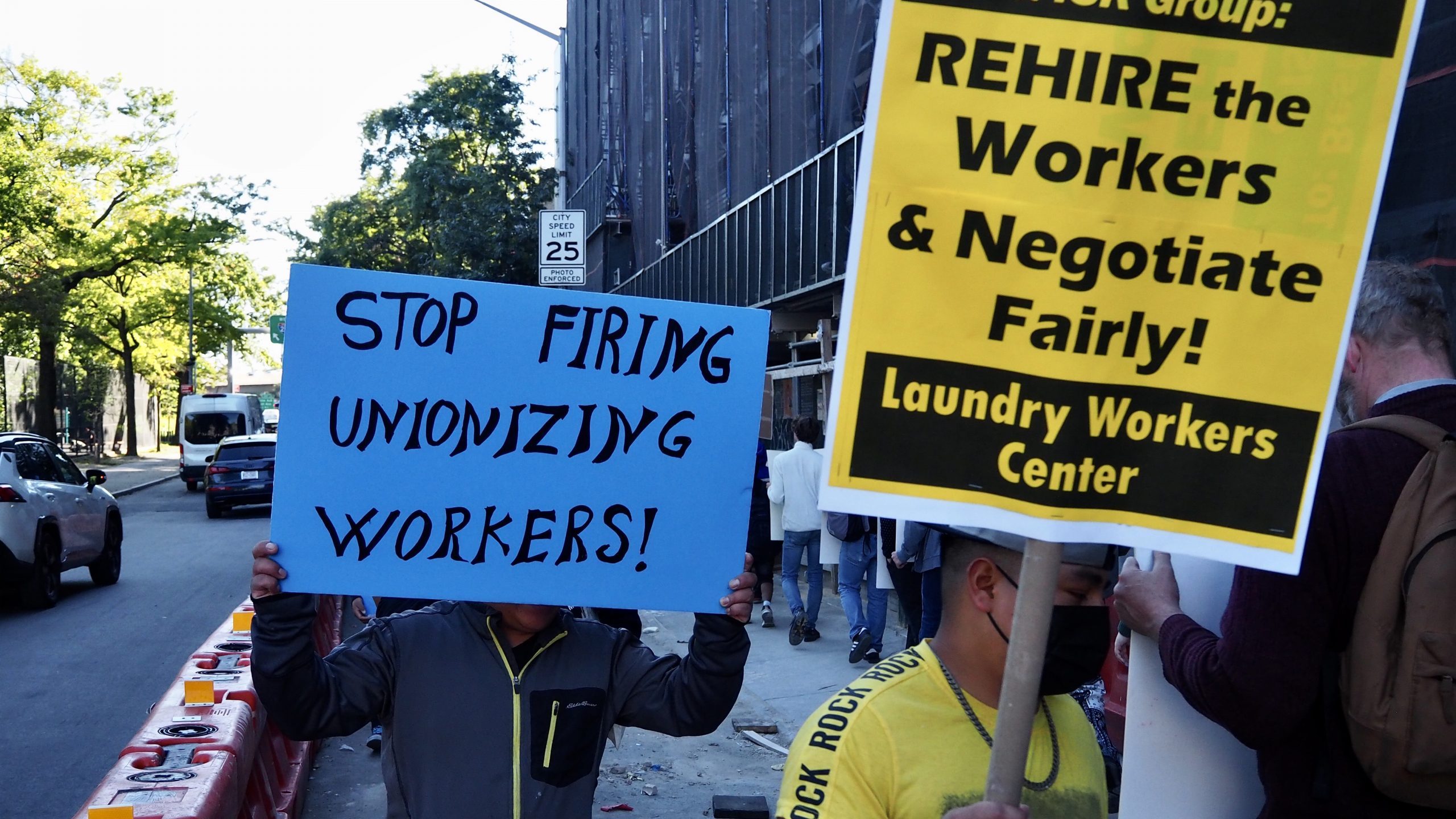

The administration’s attempt to put new restrictions on SIJS is one of several moves that have targeted immigrant minors, particularly those turning 18. Over the last year, authorities have threatened to pursue measures that would allow them to expedite deportations of minors caught illegally crossing the border and to force those seeking asylum to apply in their home countries. The authorities expanded shelter space, including opening a massive tent facility that held thousands of minors in the desert outside of El Paso, Texas. And they’ve cut millions of dollars in federal funds that provided minors with legal representation.

The amount of time that minors spent in government custody nearly doubled last year because authorities required relatives seeking custody of the young immigrants to undergo expanded background checks. And an increasing number of immigrants who turned 18 in government shelters were immediately treated as adults and transferred to Immigration and Customs Enforcement for detention.

The efforts, primarily aimed at deterring Central American minors from migrating to the United States, have largely failed. Customs and Border Protection said February was their busiest month since 2009. Their agents intercepted some 36,174 family members and 6,825 unaccompanied minors. The agency reportedly said it expects to intercept some 100,000 minors by the end of the year.

Still, while the administration has been unable to keep unaccompanied Central American minors from coming, it continues to pursue policies aimed at keeping them from staying. Last year, just 22 percent of the minors applying for SIJS in New York received approvals for their statuses, compared to 54 percent two years before, according to USCIS figures. And last year, immigration attorneys noticed that almost all SIJS applicants over 18 were being denied.

Liebmann said the Trump administration’s change in policy is a “180-degree turn” and is “at a different level when it comes to antagonism and adversarial policies.”

Robert Malionek, an attorney at Latham & Watkins LLP who is arguing on behalf of SIJ applicants, said he has seen a pattern where the Trump administration has systematically tried to focus enforcement against young undocumented immigrants.

“I can’t think of a much more vulnerable population and yet they are being targeted,” Malionek said.

A spokesperson with USCIS declined to comment citing pending litigation.

Among those affected are two teen-aged girls from Haiti – one of them 16 and the other 18 when they applied. According to the lawsuit, they were being beaten by the aunts and uncles with whom they were living and fled that country after their father abandoned them. Both applied for SIJS after arriving in New York. Attorneys said that the younger girl was awarded protection. But the older sister, known in the lawsuit as T.D., was denied. The only difference between the siblings, Malionek said, was their ages.

“The 16-year-old was able to go off to college and thrive there, whereas T.D. has not had any of the same benefits. It becomes an extremely difficult and a really arbitrary distinction between the two.”

Fleeing to save his life

Diego fled El Salvador when members of the rival street gangs operating in his neighborhood began threatening him and his friends at his high school in the country’s capital, San Salvador. One of his classmates, he said, disappeared from school for more than a week, and when he returned, he was covered in bruises. Diego said the boy refused to explain how he’d gotten injured, but he didn’t really need to either. Everyone knew it was one of the gangs.

Then another day, when Diego was taking a break between classes, sitting with friends eating churros, one of Diego’s best friends, Denis, rushed over to them, panicked and on the verge of tears. He told them that one of the gangs had forced him to kill his own cousin, as part of an initiation. If he hadn’t done it, Denis said, the gang would have killed him.

“No one asked a single question,” Diego said, recalling that moment. “Most of us didn’t want to talk about it. We wanted to ignore it and go back to focusing on our own things.”

But even though they didn’t talk about what had happened to Denis, it stuck in Diego’s mind. “I think this was a kind of warning of what could happen to us if we went down the wrong road,” he said.

A few months later, while he waited at a bus stop, two members of MS-13 gang, one of them with a buzz cut, moustache and gleaming white tennis shoes, came up to him and said they wanted him to be the next to join them. That night, he called his mother, Marta, who was scratching out a modest living at a dumpling factory in Long Island. She had already brought one son to the United States to escape the gangs there. When she heard the fear in Diego’s voice, she knew she had to bring him here too, despite the $7,000 smuggling fee, the dangerous risks of the long journey and the Trump administration’s tougher border policies.

“If you had children who have been recruited by gangs, you’d understand me,” Marta said of her decision. An assertive woman in her forties with glossy, burgundy hair and a light sprinkling of freckles on her face, she added, “I was not going to allow my kids to die at their hands.”

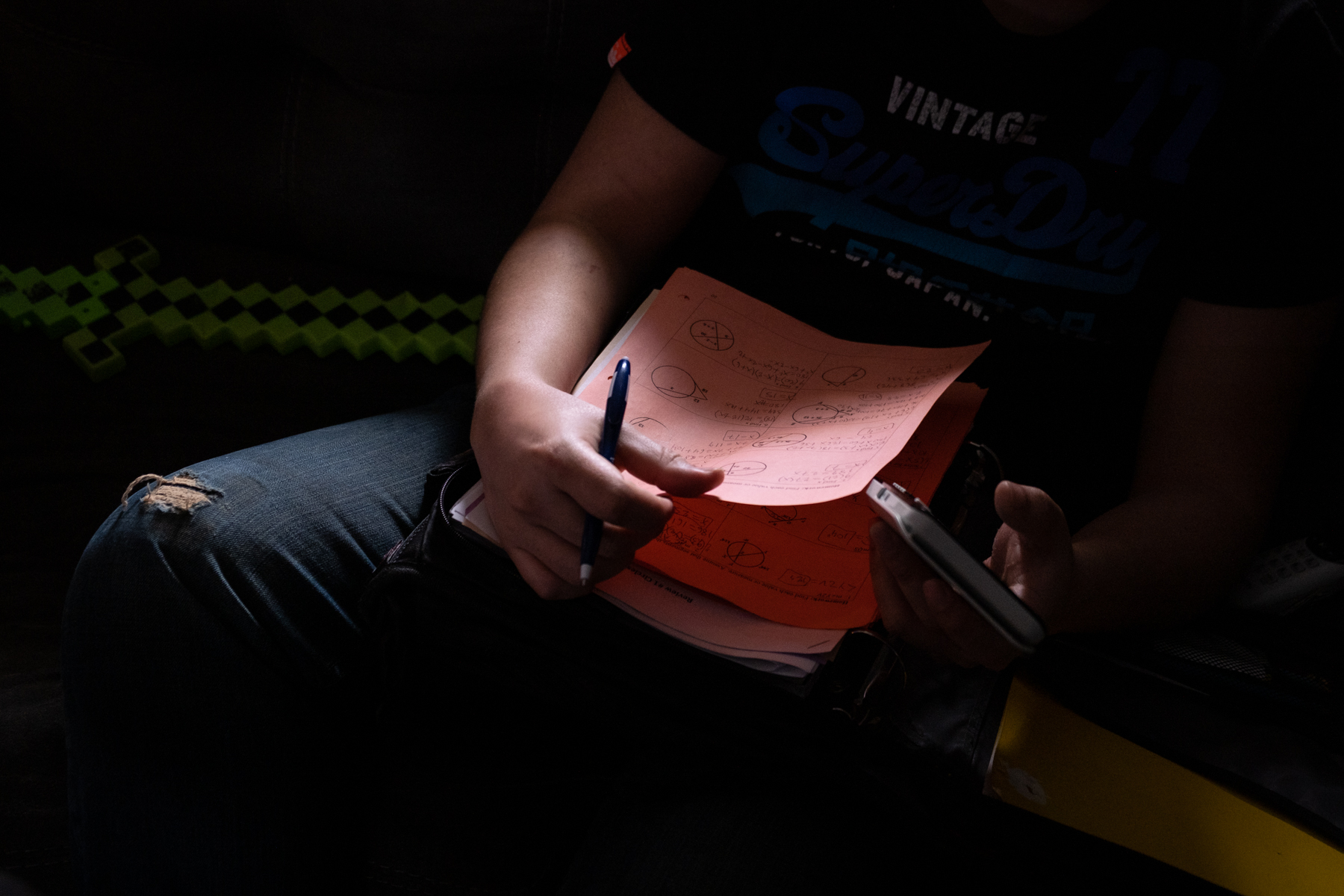

It took Diego three tries before finally making it to his mother’s basement apartment. Twice he was intercepted in Mexico and deported back to El Salvador. The first time, immigration authorities pulled the car he was in just 13 minutes away from the border, he said. The second time, Mexican authorities found him hiding in a bathroom on a bus. He finally managed to cross the Rio Grande on an inflatable raft before immigration apprehended him. Once he was here, however, he enrolled in high school, applied for SIJS and set his sights on going to college and becoming an engineer.

A status created to protect minors at risk

Under the Obama administration, immigration attorneys said, his application would have likely been approved. SIJS was first enacted in 1990, and in order to qualify, applicants needed a state juvenile court to rule that they had been abused, abandoned or neglected, and that they were dependent on the court to appoint them a guardian. New York courts have the authority to appoint guardians until a minor turns 21. However, in early 2018, the Trump administration determined that the court’s authority ended when a minor turned 18, and, without notice, began denying applications for minors over that age.

Last June, a coalition of immigration attorneys led by lawyers at Latham & Watkins LLP and the Legal Aid Society filed a class-action lawsuit on behalf of the applicants. In March, U.S. District Judge John Koeltl ruled in their favor, and ordered the administration to halt its changes.

“The policy is arbitrary and capricious,” the judgment reads.

Diego and his mother were together when they called the attorney to get the news about the judgment. They stood in the middle of their living room, lit only by a tiny window. Their attorney, who was on speaker, told them that the judge had ordered USCIS to reconsider all denied applications. Marta dove into her son’s arms. Diego stroked his mom’s back without saying a word.

“I’m so happy to learn this news,” Marta said in Spanish, tears streaming down her face. After they hung up, she pointed to a statue of the Virgin of Guadalupe on a windowsill in the kitchen, and gave thanks for the blessing, saying, “she’s given me everything I’ve asked for.”

Attorneys called the judge’s ruling a major victory. However Caicedo cautioned Diego and his mother that there are still a number of ways that the administration can block Diego’s application. Still, mother and son can’t help but begin to sketch out plans for the future.

In late January, Diego got off the bus and walked past a convenience store blocks away from his home in Long Island to pick up the mail as he would normally do. That day, he found a letter in his mailbox that he had been waiting for most of his life. “Congratulations!” it read. “We are pleased to inform you that you have been accepted to Suffolk County Community College.”

Diego jolted with excitement. He is scheduled to begin classes in November, although he is not sure that he can afford to attend as a full-time student. He is currently applying for financial aid with his high school counselor’s help. His mom says she’s willing to take another shift at the dumpling factory to help him pay for it.

In the meantime, since Diego cannot get a driver’s license, he’s started building a small motor for his bike. He said it would allow him to go as fast as 25 miles per hour, which is the top speed allowed for a motorized bike by the DMV. He checked. He read the DMV manual.

“I am proud of the person I am today and of what I am accomplishing,” he said.