This story was made possible by a grant from the Pulitzer Center

Beeping sounds filled the Brooklyn warehouse as forklifters loaded pallets of goods into Tom Tang’s 75-foot trailer. Tang, one of the many independent Chinese truck drivers in New York City, was preparing for a 15-hour drive to Saint Louis.

Tang immigrated to the United States from Canton, China, when he was 15, and started driving semis after he graduated high school. Trucking has been a stressful job for Tang, requiring him to work fifty to sixty hours each week.

The lack of sleep and pressures of the job impact Tang’s mental health. “Mondays are the most strenuous days. After we load the truck, we drive another eight or nine hours until tomorrow morning and then we go sleep for like four five hours and then wake up and start the next day,” Tang explained in Cantonese.

Despite his 20-year driving record, Tang is always afraid of getting into an accident because of his lack of sleep. He and other drivers have to quickly react to smaller cars that cut off the 80,000-pound tractor trailers and put everyone at risk, all while they face financial and managerial pressures to get deliveries done as quickly as possible.

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, truck drivers have been overworking to deliver essential goods on deadline, often exceeding their 11 hour on-the-road driving limits. The long hours, lack of sleep and social isolation have taken a toll on drivers’ mental health. That’s especially true for Chinese immigrants who face cultural and financial barriers that harm their mental health.

Tang spends most of his time in his truck, about 14 hours a day. “This is my second home,” Tang said. He sits for hours before he can get up, and eats what’s available on the road: McDonalds, Popeyes chicken or Chinese junk food.

Also read: Jing Fong’s Workers are Fighting to Keep Their Chinatown Restaurant Alive

Chee Phang, a 57-year-old Chinese-Malaysian truck driver, runs freights out of the same warehouse. Phang says he, like Tang, has no choice but to eat junk food and constantly drive. “No eat you dead. You eat you fat,” Phang said. In one year, Phang gained 30 pounds. Dr. Yan Li, a researcher and professor of Population Health Science and Policy at Mount Sinai, said drivers’ sedentary lifestyles put them at high risk of diabetes.

Sandro Galea, epidemiologist and dean of the Boston University School of Public Health, noted that trucking particularly takes a mental health toll on drivers, especially those from marginalized communities. “Trucking is one of the most stressful jobs and we know that’s going to result in social strain,” said Galea. “Marginalized groups often face the brunt of the challenges of limited assets. They have less opportunity to buy themselves the resources that fundamentally make us healthier.”

Assets can be financial, housing, or social, Galea explained, and lacking these assets makes people dependent on interpersonal relationships, the government, and themselves. For truck drivers, “the job isolates them from their social assets,” said Galea.

Chinese truck drivers are especially vulnerable to mental health disorders due to stigmatization within the Asian community that keeps them from seeking help. In Asian cultures, mental illness is often heavily stigmatized because expressing moods or psychological states can be associated with an inability to take care of oneself. Chinese cultures often believe mental illness is caused by a lack of harmony of emotions or by evil spirits.

Also read: Pearl River Mart Was Never Just a Store. It Was Always a Movement

Some Chinese truck drivers have decided to cope with mental health without professional help. When Tang is lonely and is feeling stressed, he will call his wife, whom he only gets to see on the weekend. Chinese and American songs also help Tang pass the time.

But truck driving also deteriorates the relationships people need to keep their mental health intact. Don Wong, a Chinese truck driver from Hong Kong, said long-distance contributed to the decline of two marriages. “When you become a truck driver, divorce is real hard. I divorce twice. It’s a lonely life,” Wong said.

Wong now sees his wife once a week. “You want to be with her right? But you have to go out and deliver. The times she needs me, I’m not there,” said Wong.

Wong said the Chinese culture of keeping feelings hidden is why he is hesitant to express his mental health issues to others. “I don’t want to let anybody know,” Wong explained.

Keipo Hui, a former truck driver from Macau, says he has battled chronic depression after suffering from extreme loneliness on the job. “You start getting depressed because you think about all of the loved ones you left behind and that you can’t spend time with because of your job. You miss out on all of the events, all of the barbecues that your friends have, all the fishing trips that they take. You’re never there because you just don’t have the time to be there,” he said.

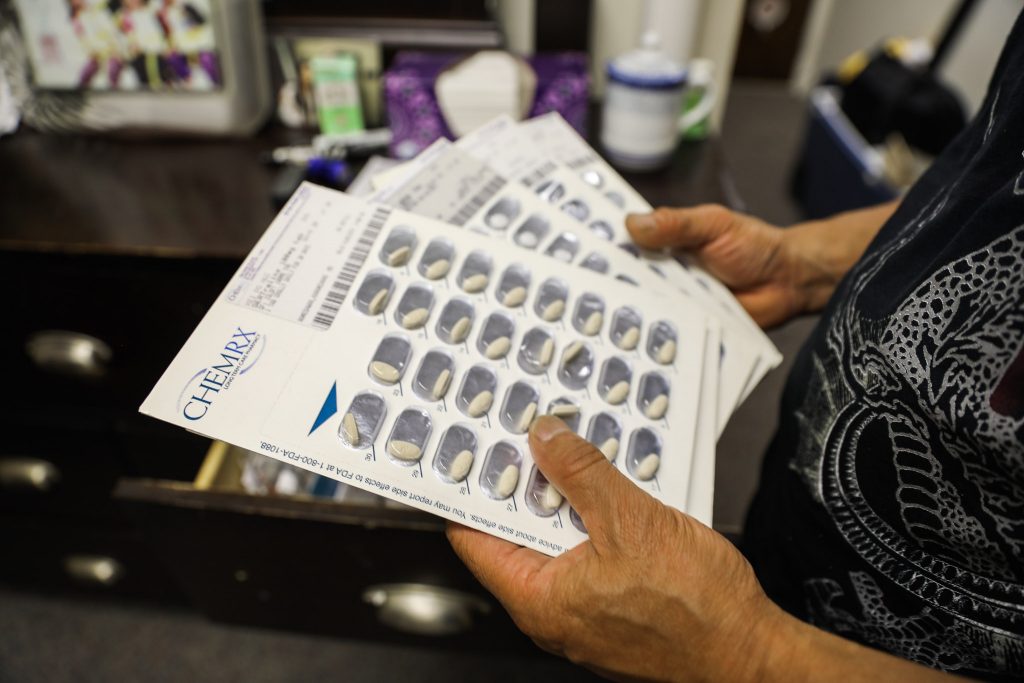

Truck drivers are considered lucky if they can spend one day a month at home with family, Hui said. Hui was prescribed Zoloft, but as a CDL driver, he could not take medications that could cause him to fall asleep over the road.

T.C. Lee, the warehouse manager for Crown Heights-based T.C. Lee Distributors where Tang, Phang, Wong, and Hui worked, retired in 2019. When asked about the labor practices of his company and mental health of his employees, T.C. Lee refused to comment and ignored a second request.

This stress affects truck drivers of all ages and races. But the stigmatization of mental health issues has led Chinese and Asian communities to underutilize mental health services in New York City, Li said. A 13-year analysis of New York City’s government funding to social service organizations serving the Asian American community conducted by the Asian American Federation revealed, Asians constitute about 15 percent of New York City’s population, but only receive 1.4 percent of the total dollar value of NYC’s social service contracts, which include mental health care. The Asian American community organization share of the City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene contracts was only .2 percent.

Because New York consolidates city contract dollars to larger organizations, smaller Asian-led and Asian-focused service providers are often the first to lose funding when budgets are cut. Over the 13-year period, the analysis found that Manhattan received the bulk of contract dollars totalling $473 million, compared to Brooklyn ($67 million) and Queens ($60 million). Manhattan has the third highest concentration of Asian Americans among the five boroughs.

Also read: A Chinese Family Trip Turned Into an Immigration Nightmare

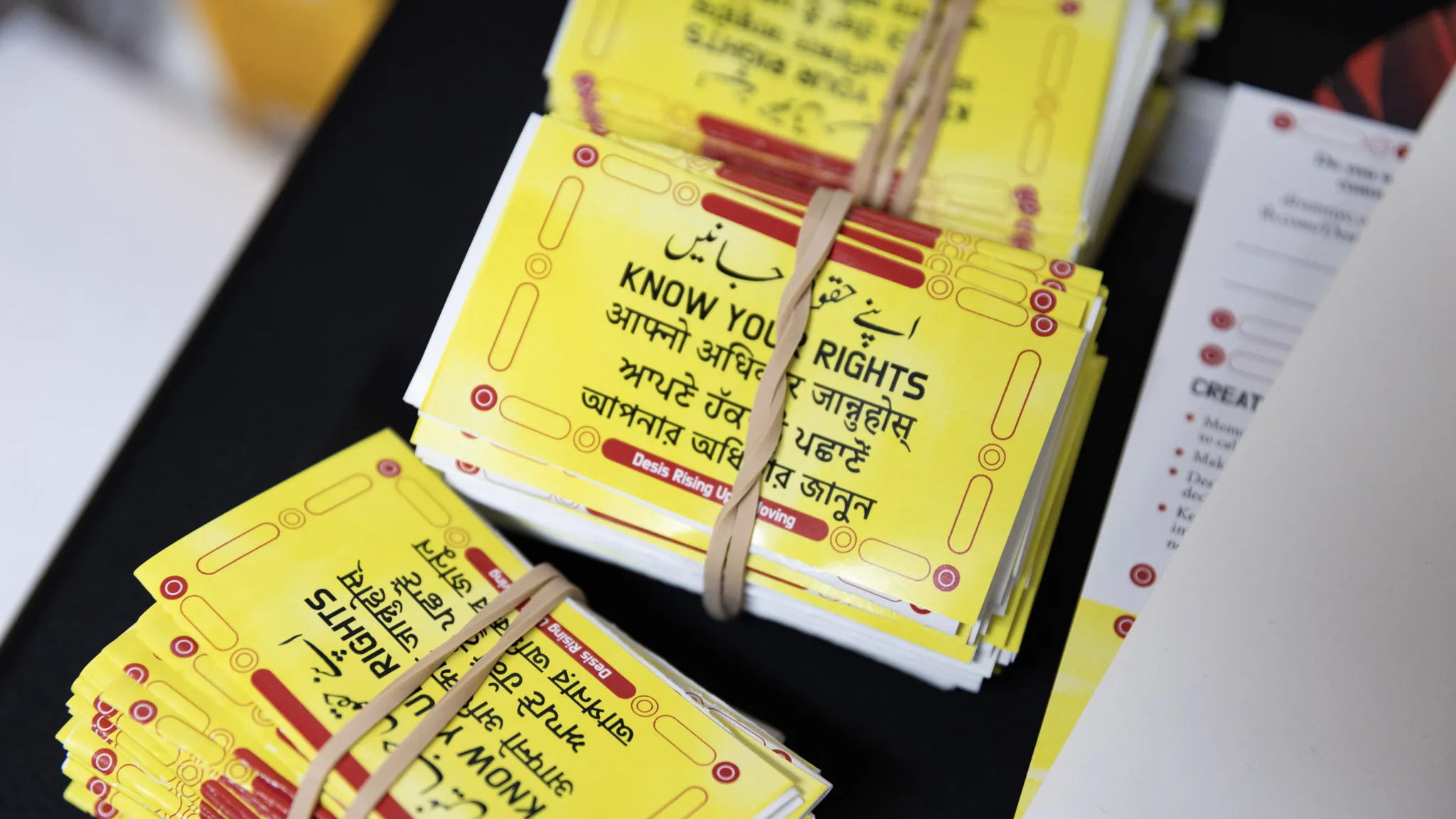

There aren’t many mental health services offered in major Asian languages in New York City, making it even harder for Chinese immigrants like Tang, who don’t speak English as their first language, to access help. A lack of affordable insurance health insurance also stands in the way.

“The United States has the highest health care cost in the world. Without health insurance, most people cannot afford to see a doctor,” Li explained. As an independent driver, Tang has to pay $2,000 a month for his own health coverage.

Phang would meanwhile have to pay $600 a month for coverage, meaning he’d have to work a whole week at $25 an hour to pay for monthly insurance. “I want to buy it, but it is $600 a month for the insurance, how can I buy? EXPENSIVE,” Phang yelled. Phang visits the doctor once every three months, but pays out of pocket, making visits costly.

An annual report on poverty measures from New York City’s Office of the Mayor found that Asians in the city had the highest poverty rates from 2013 to 2017 when compared to non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, and Hispanics. Poverty not only predisposes people to more economic stress, but restricts their ability to access mental health treatment.

But living in expensive New York City means, Chinese truck drivers can’t afford to refuse deliveries.“Like they say, if the wheels aren’t turning, you aren’t earning,” Hui said.

Still, combating mental health issues among the Chinese immigrant trucking community will require more than just better health insurance coverage and pay. “Stigma is a label. It’s a label that says this condition they’re other, they’re different,” said Galea, the epidemiologist. “And the way to change it is by breaking down those barriers by talking about it. It requires conversations within the Chinese community.”

Also read: Why I Fled Donald Trump’s America