In August last year, the streets of Chinatown were deserted and its storefronts were shuttered, but one afternoon that month, hundreds gathered in front of 46 Mott Street. “I’ve always wanted to try this,” said Patrick Mock, standing in front of the bakery he manages. “Show me what community looks like!” he shouted to the crowd.

Two days prior, Mock had gone viral on Twitter, where he was captured in the same spot, confronting Mayor Bill de Blasio for turning his back on Chinatown. Mock would ride out this fame through the pandemic year; his declarations made him the face of mutual aid efforts to save Chinatown; praised by local politicians and Hollywood A-listers (Will Smith donated $50,000 to Mock’s Light-Up-Chinatown project last December). “This is the start but I’m using this as a platform,” he said on video to Instagram celebrity Nicolas Heller, “neighbor helping neighbor; community helping community right now.”

But a group of busboys, waiters, and service staff who worked under Mock at the now closed Joy Luck Palace, have presented a different reality of Mock’s relationship to the Chinatown community. They are accusing Mock and three business partners of evading nearly $1 million in back pay since the workers filed and won a lawsuit nearly two years ago.

Last Thursday, newly angered by Mock’s heroic public image, these workers gathered at the former location of Joy Luck Palace, a short-lived cult favorite dim sum restaurant that Mock was a co-owner of. They called on Attorney General Leticia James to prosecute Mock, for the wages to be returned by Mock and Joy Luck associates. They also called out local elected officials, including Assemblymember Yuh-line Niou and city council candidate Jenny Low, for aiding fundraising efforts to “line the pockets of sweatshop bosses,” as Vincent Cao, a former waiter at Joy Luck said in a speech. Niou and Low helped support Mock and his fundraising efforts, volunteering at the bakery throughout the year.

When it opened, Joy Luck Palace’s popularity was immediate (Eater’s senior critic went twice in one weekend during the first month). “Business was always good, you could hardly get a seat any weekend,” recalls Cao, “all the workers kept a good attitude, and every month our then boss Yong Jin Chen, would meet with the workers and praise us for good performance.”

Although their hourly wage was way below average — $5 an hour, with a few cents raise throughout the two years — the workers were able to live off of tips due to the restaurant’s unceasing popularity.

In January 2018, despite its reputation, Joy Luck’s Board of Directors abruptly ceased walk-in operations, “to avoid being eliminated by the market.” The workers, although initially bewildered by this news, later recognized this closure to be a culmination of months of suspicious activity.

Two months before the closure, Cao and other service staff had stopped receiving paychecks altogether. “Without the tips, we simply could not have survived those two months,” Cao said. But even as tips had become sparse, owners of Joy Luck began moving food items out of the restaurant and into other establishments that were purportedly also owned by them, running Joy Luck dry, and chasing business out, Cao recalled. “By noon, there would be no food left at Joy Luck.” Cao suspected this was a tactic used by the owners to move around their assets.

Also read: AAFE, a Nonprofit and One of Chinatown’s Largest Landlords, Has a Troubling Record

The following September, still without their owed wages, Cao and others filed a civil lawsuit against Joy Luck. The judgment became a default win for the workers when Mock along with co-owners of Joy Luck, Qing Wen Chen, Tak M Yee, and Yong Jin Chan failed to show in court. The defendants were ordered to pay back $943,000 in wages; each worker was owed individually anywhere from $11,000 to $65,000. Nearly two years later, Cao and the 18 other plaintiffs are still waiting to collect, they explained, while Mock and the associate’s assets are impossible to track.

“When there’s a default judgement, collecting becomes harder than getting the judgement,” explains Thomas Power, the lawyer that represented the workers. According to a 2015 study by the Urban Justice Center, The Legal Aid Society, and the National Center for Law and Economic Justice, 43 of the 62 identified New York federal and state court wage theft judgements that employers have failed to pay in recent years were default judgements, totaling $25 million owed to over 200 workers.

Experts estimate as much as $50 billion a year is stolen from workers. “Enforcement is the perennial issue,” Chaumtoli Huq, an attorney at the Worker’s Right Clinic told Documented. “The DOL however is entrusted to enforce NYS labor laws, so why do they, as a matter of policy, not enforce it to its full extent?”

The allegations against Joy Luck reemerged partially due to Mock’s newfound publicity, but also as a means for workers and local labor organizers to emphasize the need for legislative support of the Securing Wages Earned Against Theft or SWEAT bill. In 2019, SWEAT passed the New York State legislature but was vetoed by Gov. Andrew Cuomo. The bill was recently reintroduced, with wage lien as its focus, which would grant workers more enforcement power in the collection process by allowing workers to freeze an employer’s assets before the legal process even begins. Currently, a worker is only able to file a lien on an employer’s assets after the judgement has ruled in their favor.

Your help lets us keep reporting on immigrants communities. Become a member today.

“The bill doesn’t do more than workers get the pay to which they are entitled to,” says Huq, who likens it to the already existing mechanics lien and a recently passed wage lien bill in Washington state.

For Sarah Ahn, the director of the Flushing Worker’s Center, this bill carries specific urgency. “What I’ve seen in the last decade is that employers have become completely brazen, they know they’re untouchable,” Ahn said, pointing to techniques, legally known as “judgement proofing,” that employers use to transfer assets—sometimes selling property to a family member or closing the business and moving the assets to an entity elsewhere.

At the same time Joy Luck’s business began to deplete, 46 Mott opened down the street, offering a similar signature dish as the historic tofu-shop that existed before, which brought its own set of legal battles. Tak M. “John” Yee operated 46 Mott initially. It’s now owned by Qing Wen “Tony” Chen with Patrick Mock as manager. All three are named defendants in the worker’s lawsuit.

Also read: How Mutual Aid Supported Chinatown When the Government Failed

This practice is not enacted in the shadows either. One clinical legal education organisation has offered training for lawyers to learn how to make their clients become “judgement proof” to hide assets and ward off creditors and collectors.

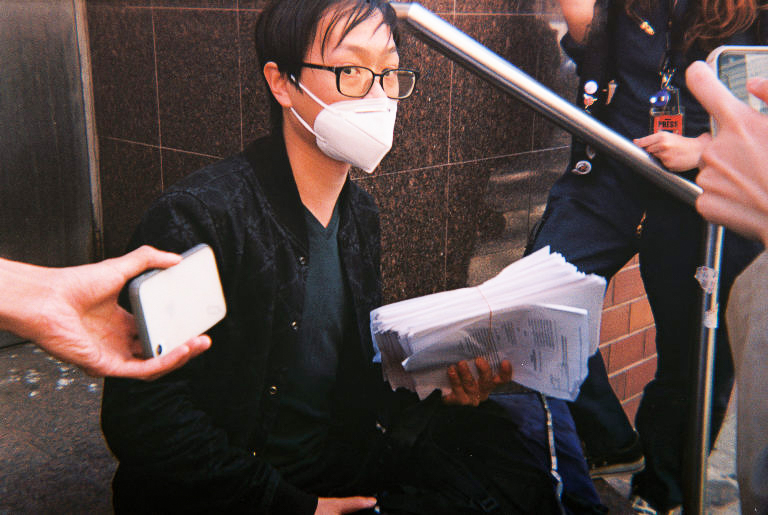

While the workers were testifying, Mock sat on a nearby stoop. With the similar brazen sweat-drenched intensity he had in his first viral video confronting de Blasio, Mock attested to reporters that he had been frauded, offering to show them his house and his bank account. “I have nothing,” Mock said.

Niou and Low are some of Mock’s strongest supporters, and have used their public platform to defend his innocence amidst demands from the workers to denounce his alleged theft and negligence.

Niou told Documented that to her knowledge, Mock had been signed on to co-own Joy Luck six months before it’s closure, though at the time of closure, in a National Labor Relations board complaint filed to the NLRB by the 318 Restaurant Workers Union, the only restaurant workers union in Chinatown, it’s indicated that Mock owned the place from 2016 onwards.

Ultimately, Mock’s recent pronouncements to protect Chinatown and help its residents recover from the pandemic have newly angered the workers. “So many businesses were hurt by the pandemic, why must our electeds help this one, when it is not an honest business?” said Cao, “we must fight for something different in order to recover.”

“I have two kids, one is 5 years old and one is 10. My wife has health conditions and has not been able to work for 10 years,” he adds, “the worker’s goal was never to become rich. We just want a job, a place to work, a way to make a life.”