Soleima Santiago held off on getting vaccinated for months after the shots became widely available to New Yorkers. She works two jobs — a morning stint at a hair-dresser, and an evening shift at a restaurant — and couldn’t find a window to get inoculated.

“I didn’t have any time,” Santiago, 19, a native of El Salvador, said Saturday at the Joseph P. Addabbo Health Center in Far Rockaway, while she waited to get her first vaccine shot. “I work from 8 a.m. until midnight.”

It is a familiar predicament across much of the City. Vaccination rates in some neighborhoods with high foreign born populations have lagged behind the city average for various reasons — including tight work schedules, fears of adverse reactions, rampant misinformation fortified by the geographical isolation of some communities like Far Rockaway, and a shortage of inoculation sites.

Despite aggressive efforts to encourage incoulatons, vaccination rates in one zip code on the Rockaway Peninsula in Queens still trail well far behind the City’s norm.

The Edgemere and Far Rockaway zip code of 11691, has the lowest vaccination rate in the City. Here, only about 34 percent of individuals of all ages are vaccinated, city data shows, compared to more than 55 percent citywide. Vaccination rates in this swath of the Rockaway Peninsula even lag behind the numbers in Alabama, the state with the lowest percentage of fully vaccinated people in the nation (35.02%), according to the Johns Hopkins University of Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center.

Far Rockaway has become emblematic of the many hurdles hindering vaccination efforts in low-income urban neighborhoods with significant immigrant populations. Roughly one-third of the almost 70,000 residents of zip code 11691 are foreign born, mostly from Latin America, according to U.S. census data. The median household income in zip code 11691, on the eastern side of the Rockaway Peninsula, is about $50,000 – about $14,000 less than the average NYC household income.

By contrast, the average household income is almost $106,000 in Breezy Point, on the peninsula’s western flank. There, in zip code 11697, about 79 percent of residents are fully vaccinated, far above the city average.

In recent weeks, community activists, lawmakers and others have made a renewed push to bolster inoculations in the Far Rockaway area. “We’re at a pivotal moment in this fight — we don’t want to go back to where we were last year,” Queens Borough President Donovan Richards said Thursday, during a visit to Far Rockaway with other officials aimed at encouraging residents to get vaccinated. “Reminder — Far Rockaway shut down. Reminder — bodies upon bodies at our hospitals.”

Far Rockaway is “this little microcosm of New York City,” said Miriam Vega, the Chief Executive Officer of the Joseph P. Addabbo Family Health Center, a major community health hub which has locations in Rockaway, Southeast Queens and Brooklyn. “The issues that New York City faces as a whole, they are extremely punctuated there.”

The key to increasing vaccinations, immigrant advocates say, is to quell fears about the shot, and boost the availability of appointments and accurate information. Often, this means walking the streets and seeking out residents.

For months, advocacy groups have been aggressively pitching vaccines in immigrant communities. They’ve translated paperwork into Spanish and other languages, hired bilingual health-care workers and dispatched buses with vaccine teams to every borough, while expanding vaccination periods to weekends and after-work hours. Advocates have also been posted outside vaccination sites, seeking to allay fears and reminding people that neither lack of health insurance or uncertain immigration status hinders eligibility.

Also read: “COVID-19 is Creating More Homeless Undocumented Immigrants in New York”

“Continuing to keep trusted messengers at the forefront of the outreach is essential,” said Ellie Alter, the COVID-19 outreach coordinator for Make the Road New York, an advocacy organization that has been setting up clinics to help immigrants and others get vaccinated throughout the city. “And to take a more sort of deep-canvassing approach where we understand that these are ongoing conversations that require multiple touches.”

Still, in the 11691 zip code, a community where about 22 percent of residents speak Spanish at home, there aren’t enough materials in Spanish — and existing Spanish-language pamphlets and brochures are often written without cultural context that fails to ease people’s concerns, Dr. Vega from Addabbo said. Some residents interviewed agreed that this contributed to the hesitancy about the vaccine.

“There is a little bit of information in Spanish, but there isn’t enough,” said Aldo Esteban, a 19-year-old Guatemalan restaurant worker who was getting his first shot at Addabbo on Saturday. “People sometimes can’t do the homework of really investigating.”

In the Far Rockaway zip code of 11691, 25 percent of residents are Hispanic and 47 percent are Black. Across New York City, 43 percent of Hispanic residents are fully vaccinated, and 32 percent of Black residents are fully vaccinated. There is no available city data that breaks down the percentage of vaccinated residents by demographics in zip codes.

Some individuals, especially those who are undocumented, are wary of filling out forms asking personal questions that they don’t fully understand. Many immigrants, like Santiago, who juggles beauty parlor and restaurant gigs, say they can’t miss work for the shot. Others worry that reactions to the jab could leave them bed-ridden or even hospitalized, potentially exposing them to a lack of income and to medical bills prohibitive for those lacking insurance.

“We have to understand that, in the context of this community, where folks are often living paycheck to paycheck, being super sick is not just a matter of what that’s going to feel like — but fear of not being able to work for a week and not having the job security,” said Alter from Make the Road New York.

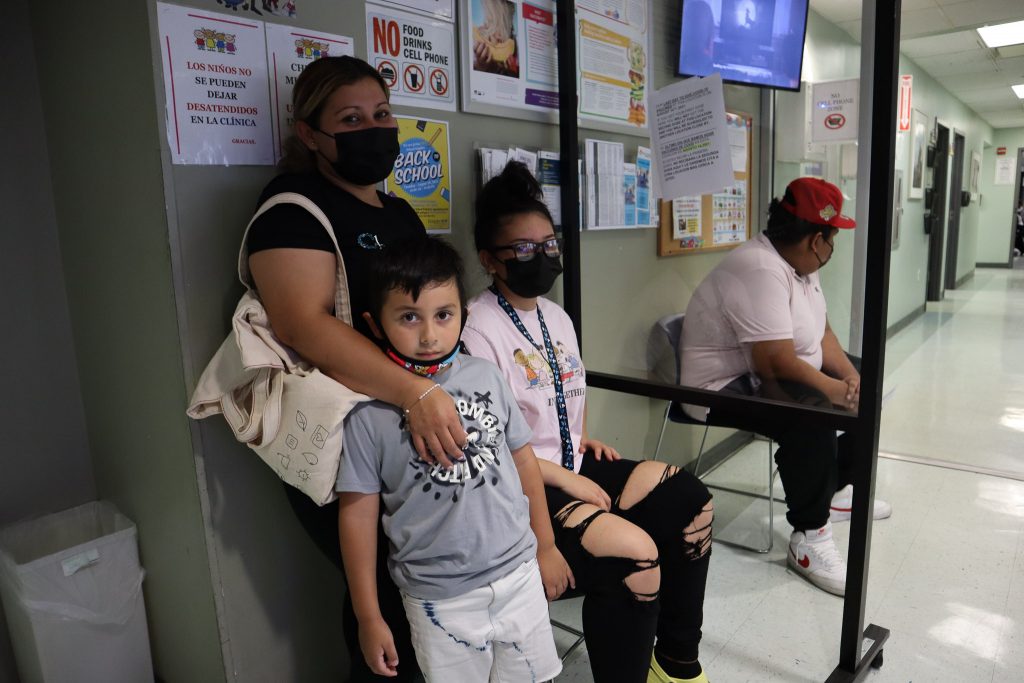

Floridalma Linares, from El Salvador, stood in line on Saturday at the Addabbo center with her 15-year-old son, who she was accompanying to get the shot. Linares, 40, had not yet been vaccinated and wasn’t planning to for at least several more months. She contracted COVID-19 in March of 2020, and feared that the vaccine could bring back the debilitating symptoms that she suffered last year. “I don’t want to feel that way again,” she said.

Considerable misinformation about the vaccine has been circulating in Far Rockaway, a relatively insular community where many people both live and work in the surrounding area, and where there are relatively few reliable health-care providers. Hyperbolized accounts about incapacitating side-effects spread quickly by word of mouth.

“You hear a lot of comments, and you don’t know what reaction you’re going to have to the vaccine,” said Dilia Broncano, from Guatemala, who was at Addabbo on Saturday with a hand on the stroller of her one-year-old daughter. She was there to get her second shot, but was nervous because of discussion circulating in her community about the side effects – and many of her family and friends haven’t gotten vaccinated because of this, she said. “It’s all because of what you hear – you just don’t know what reaction you’re going to have,” Broncano, 26, said.

In Far Rockaway, “the physical geographical isolation leads to isolation of information,” said Dr. Vega, expressing a sense of urgency about stepping up vaccinations. “The longer this goes on, the more entrenched some people get in their positions of being anti-vaccine.”

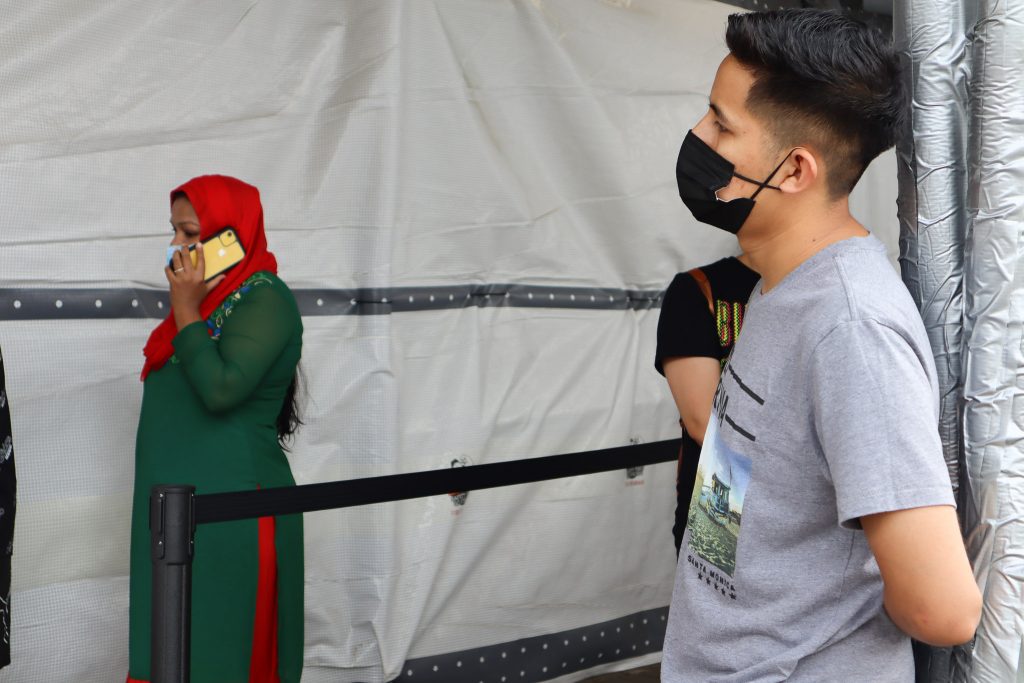

On Saturday, dozens of individuals lined up on Central Avenue in Far Rockaway outside Addabbo, which is a non-profit health center. Typically, about 300 people are vaccinated there during the weekend clinics. Health professionals chatted with clients, guided them through the paperwork, and encouraged them to bring others to get their shot. Families, many with young kids, chatted in Spanish, Mandarin, and other languages.

Linares, who is six months pregnant, was also fearful of what could happen to her baby if she got the vaccine. “I’ve heard you’re not supposed to get the vaccine if you’re pregnant,” she said. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, however, recommends that expecting mothers be vaccinated because they are more likely to get severely ill from COVID-19 compared to others. But the CDC also notes that there is still limited data on the safety of COVID-19 vaccines for people who are pregnant.

Roberto Linares, the son of Floridalma Linares, said he had decided to come get the shot on Saturday because he wanted to be safe to start school. Roberto, 15, was also hoping to go visit family members back in El Salvador, and thought he might need to be vaccinated to travel. “I have to go to school and there are a lot of risks with that,” he said, adding that he was “a little nervous” about the vaccine because he didn’t want to feel sick afterwards.

More people were lining up to get the shot on Saturday than on previous weekends, staffers at Addabbo said. Some speculated that reports of the $100 incentive recently announced by the City was drawing clients, along with the upcoming start of the school year and fears about the Delta variant.

About 70 percent of the Addabbo staff is from the community, Dr. Vega said, a fact that has helped foster trust.

Some, like Diana Catalan, the clinic director, were born and reared in the neighborhood. People recognize her on the street and ask her about the vaccine. For Catalan, the vaccination mission is close to her heart. Her father, who came to Far Rockaway from Guatemala in the early 1980s, passed away from the virus in February.

“It was horrible,” said Catalan, who channels that personal pain into advice for fellow residents. “If you love your children, you should think about getting vaccinated,” Catalan tells people. “I see what it looks like to be sick, I had to take care of my dad, so I wouldn’t wish that on anybody.”

She views every vaccine administered as a victory. “People tell me: ‘que dios me la bendiga,’” Catalan said, using the Spanish phrase for ‘God bless you.’ “That, to me, feels like they trust me—and that I wouldn’t encourage them to do something that is not the right decision.”

Esteban, the restaurant worker who was getting his first shot on Saturday, said reports of rising numbers of infections had helped motivate him to get the shot. He is the first one in his family to get vaccinated, and he’s hoping that his own decision to get the shot will encourage both his loved ones and his co-workers to do the same.

“This is the moment where we can’t wait anymore,” Esteban said in Spanish. “I don’t want to hurt other people. We have to help…that’s the message we have to send.”