As New Jersey continues to cut ties with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention in the state, an open question remains as to what will happen to local residents arrested by the agency. Since the handful of facilities that detain immigrants in the state started ending their contracts, ICE has transferred detained immigrants across the country separating them from their families and lawyers in the process.

The agency chooses to send individuals across the country, when there is another alternative — albeit a flawed one, according to advocates — a program called Alternatives to Detention (ATD), where immigrants can live outside of detention facilities, while still supervised by ICE.

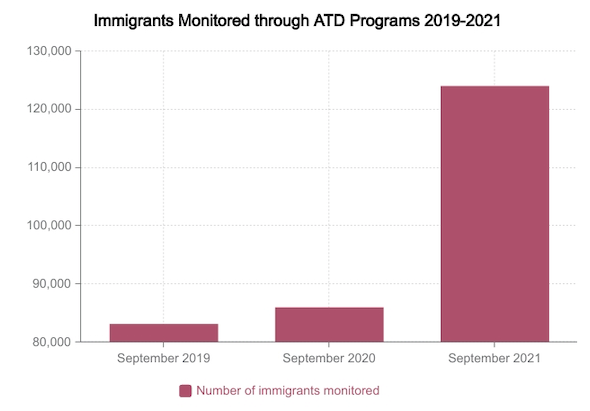

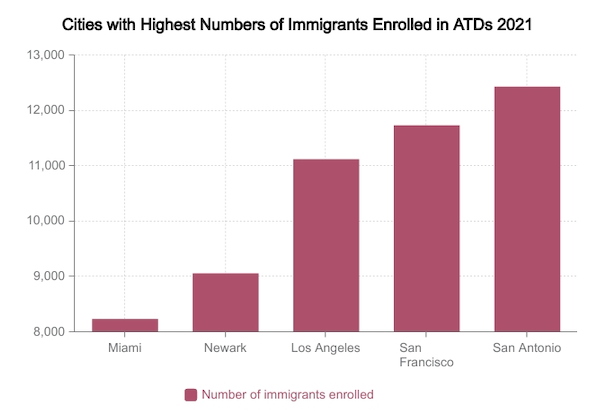

The program has been in use since 2004, and as of September 13 there were more than 124,000 immigrants supervised through the program, according to Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. The Newark ICE office had the fourth highest number of people monitored through the program as of September 13, with more than 9,000 individuals enrolled in the program.

And since the end of May, the number of people enrolled in ATD, supervised by the Newark ICE office, has grown steadily from less than 7,000, up to 9,062, data from TRAC shows. The program is also successful. A 2014 Government Accountability Office report found that 95 percent of immigrants on “full service” alternatives to detention appear for their final hearings.

Also Read: Advocacy Groups File Complaint About Abuses at New Jersey ICE Jail

But advocates caution that more people in the program doesn’t necessarily mean less people in ICE detention facilities. The program also has serious consequences on the lives of the people who are in it. Immigrants have described ankle monitors burning their skin, causing inflammation, sores and bleeding.

In the 2021 fiscal year, according to TRAC data, ICE detained 23,014 immigrants at detention facilities often riddled with human rights complaints. Most have no criminal record. Just two years ago, in September of 2019, the U.S. held about 51,000 people in ICE custody daily. The numbers of people in detention, however, have risen since the beginning of Joe Biden’s presidency — and so has the number of those enrolled in ATD programs.

But what exactly are the alternatives to detention that currently exist and how do they work? And what about these alternatives needs to be changed, according to advocates? Here is a look at what the ATD program is like.

What do the alternatives to detention look like?

The main alternative to detention program is called the Intensive Supervision Appearance Program (ISAP), which is run by a subsidiary of the GEO Group an international private prison company that partners with ICE. Employees of GEO Group supervise people in the ISAP program through check-ins at ICE offices, home visits from officials, ankle monitors and a new technology called Smart Link — a smartphone application which uses facial recognition to confirm identity along with GPS location monitoring.

In fiscal year 2021, more than 30,800 immigrants have been monitored through ATD GPS tracking devices, including ankle monitors, across the country, as of Sept. 11, according to a Documented analysis of ICE data. In the same time period, more than 66,000 immigrants were monitored through the SmarkLINK ATD program nationally.

In Newark, the majority of immigrants in the ATD programs, about 63 percent, are monitored through SmartLink technology, according to TRAC. About 15 percent of immigrants in the Newark area are monitored through GPS ankle monitors.

Who is enrolled in Alternatives to Detention?

Immigrants who are in immigration court proceedings, but who are not deemed a flight risk or danger to society by an immigration judge, may qualify for ATD.

People who are monitored in this program include longtime residents of the United States, green card holders who are in removal proceedings, and newly arrived asylum seekers, among others, said Michael Kaufman, a senior staff attorney for the ACLU of Southern California. ICE has a lot of discretion over who they decide to detain, and who they decide to put in an ATD program, said Setareh Ghandehari, the advocacy director for the Detention Watch Network. “The decision-making process is not transparent,” she said.

Also Read: Hudson County Officials Move to End Contract With ICE

For families who are now entering the United States and seeking asylum, it’s unclear who goes through the family staging centers in hotels, and who moves through the family detention facilities, Ghandehari said. Every family is enrolled in ATD programs after a stay in one of those facilities or staging centers, however. At least one adult in the family is on some sort of surveillance mechanism, whether that’s through an ankle monitor or a smartphone application, or something else, she said.

Heidi Altman, the director of policy at the National Immigrant Justice Center said that “opacity is a hallmark of ICE’s ATD program.” It’s very difficult — if not impossible — for immigrants themselves, and their advocates, to know why they are being put into an ATD program versus taken to ICE detention, she said.

Some immigrants in New Jersey were released due to the pandemic and were enrolled into the ATD program as the virus spread through detention centers, only to be brought back into ICE custody soon after.

Concerns about the Alternatives to Detention program, as it exists now

Many advocates say they have concerns about the way the program is operated.

Detention Watch Network, an organization which doesn’t support alternatives to detention as they exist now, instead focuses on the release of all immigrants from ICE detention and surveillance. The program, some advocates including those at Detention Watch Network say, never actually decreases the number of people in detention facilities.

“What we’ve seen is that when funding for ATDs goes up, funding for detention also goes up,” said Ghandehari. “What it does is actually increase the number of people overall who are caught in this sort of enforcement and surveillance system.”

She added: “Rather than reducing the number of people that are subject to the inhumane detention conditions, we are actually just adding a new group of people who are experiencing a different kind of harm.”

At the ACLU, Kaufman says that the organization has found that individuals are often put under “really intensive conditions and supervision,” especially with ankle monitors. The monitors, Kaufman said, are “painful, humiliating, and really interfere with their day to day life.”

Extensive studies have shown that ankle monitors have caused serious psychological and physical harm. Swelling, cramps, blisters and permanent scarring have been reported by immigrants who have had to wear ankle monitors. In one instance, a woman even reported that her ankle monitor burst into flames, and she experienced burning on her hands as she tried to take it off.

With ankle monitors, “people have talked about it as this sort of slow torture,” Ghandehari said.

Immigrants have also experience increased stigma because of ankle monitors, including increased interactions with police who questioned them about their ankle monitor use, the North American Congress on Latin America and other organizations have reported.

The ACLU has had a number of clients who have faced problems at work because their supervisors do not want the ankle monitors to be visible. ICE has also put geographic restrictions on where people can travel, which can interfere with ICE check-ins themselves if individuals have to go far for them. Technical violations can also happen easily and cause the immigrant to inadvertently violate the conditions by no fault of their own, for example if the battery of an ankle monitor dies or their phone has no cell service and they miss a check-in call, Kaufman said.

“This intensive supervision isn’t accomplishing anything besides putting people at risk of potentially being detained,” he said.

Also Read: New Jersey is the First East Coast State to Ban Further Contracts with ICE

In addition, immigrants have reported that ankle monitors only serve as a reminder of the trauma they have undergone, especially for victims of domestic and sexual violence, according to complaint letters sent to ISAP, cited in a California Law Review journal.

The SmartLINK technology, too, worries advocates. In a recent report published in June by Just Futures Law and Mijente, organizations which support immigrant rights, advocates note that while ICE says that the application does not monitor an immigrant’s location in real time, it does have the ability to do so. And SmartLINK’s privacy policy, the report says, can share “virtually” any information that is collected through the application with a supervising officer, even if it is “beyond the scope of the monitoring plan.”

Ultimately, advocates say, this program creates a psychologically and physically harmful environment for immigrants who, through these tactics, feel as though their every move is monitored and scrutinized.

For many of the immigrant clients who have worked with National Immigrant Justice Center, Altman said, it’s been challenging for them to get information about how to have the most demanding supervision requirements reduced, or what triggers an increase in supervision requirements. “So it ends up feeling like a very arbitrary sort of imposition of power on the person who’s in the system,” she said. “And that, in turn of course undermines trust or faith in the integrity of the system as a whole.”

Alternatives to Detention Programs are cheaper than ICE detention

Data shows that the Alternatives to Detention program actually costs the government less than holding immigrants in ICE detention centers for prolonged periods of time. From 2016 to 2017, ICE spearheaded a Family Case Management Program (FCMP), which focuses on community-based alternatives for detention, particularly for families who had young children, women who were pregnant, and victims of domestic violence, among other individuals. Each family worked with community organizations along with a private contractor.

Available data on FCMP shows that not only did 99 percent of people comply with ICE monitoring requirements, but that the program only cost $38.47 per family per day — while at the time, the cost was $237.60 per family in detention.

“It’s much cheaper” to have someone in the alternatives to detention program than to have someone actually detained, Kaufman said. It costs the federal government an estimated several hundred dollars to detain a single person every day, while ATD programs can cost $10 to $20 dollars a day, Kaufman said. “The federal government stands to save millions and millions of dollars,” if choosing these supervision programs, he said.