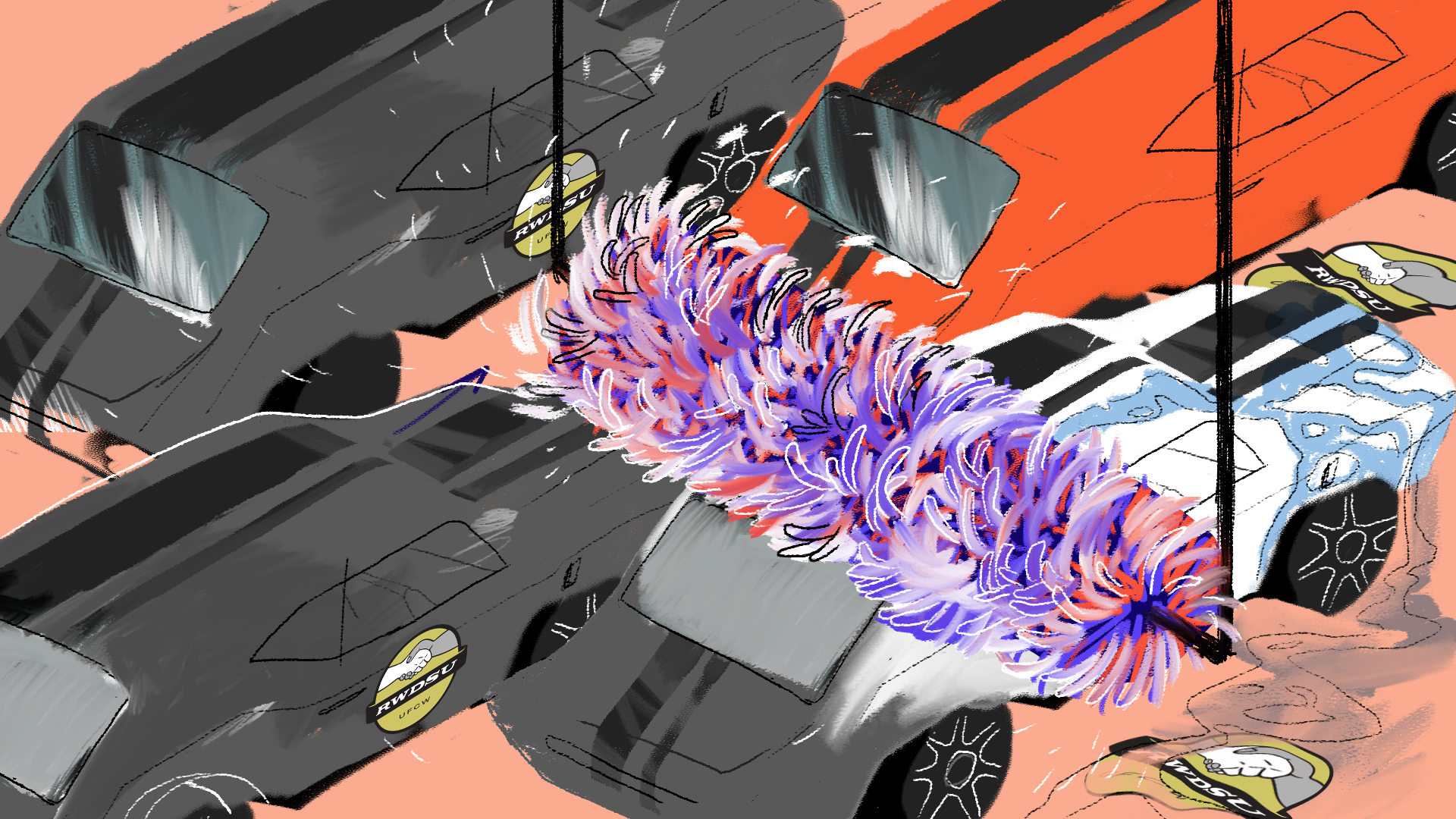

On April 24, 2013, when their shifts were over, the workers of Jomar Car Wash in Flushing, Queens, voted in favor of unionizing under the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU).

They were mostly undocumented immigrants from Latin America and they had been forced to work 12-hour shifts, six days a week, without overtime pay. That night felt like a moment of liberation. It also represented a triumph for the immigrant-led labor movement in New York.

Jomar —its legal name, although its street sign reads Main Street Car Wash— was the sixth car wash in the City to unionize under RWDSU since 2012. Those efforts attempted to counter the pervasive abuse in the car wash industry: Two-thirds of the workers were paid less than the legal minimum wage, while three-quarters of them didn’t receive any kind of overtime pay, according to advocates. Some workers made as little as $4 per hour.

After that night in 2013, the labor movement won several more battles, with RWDSU unionizing a total of nine car washes in the City over the next three years. However, the backlash from car wash owners was fierce. Today, just two car washes keep their unions. Some of the car washes shut down while others forced a vote to decertify the union as recently as in November.

The last establishment to get rid of the union was Jomar, owned by Jose Pires, and co-owned at some point by Fernando Magalhaes and John Lage, who was dubbed the carwash kingpin by The New York Daily News.

Also Read: These Laundromat Workers Were Fired After Forming a Union. Now They’re Fighting Back

In many ways, Jomar Car Wash has been the epicenter of the struggles of the immigrant-led labor movement in the car wash industry in New York, which is confronting exploitative owners whose business model has relied on gross underpayment and wage theft, advocates and organizers say.

On November 11, the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation announced that with their “free legal assistance,” the RWDSU union was forced out of Jomar, which was unionized for eight years. The Foundation, which calls itself “a charitable organization,” has deep connections to the Koch Brothers and the John Birch Society, which espouses radical and ultra-right politics. The foundation has sued on behalf of workers arguing that union fees are unconstitutional.

The foundation worked with Ervin Par, a Jomar worker, who was featured in a propagandistic 2018 video, to decertify the union. In an interview shot at Jomar, Par claimed that RWDSU did not have to defend workers from anybody, and then he repeated the sentence in strained Spanish. Par could not be reached for comment.

Violent backlash

In May 2013, just over a month after the workers at Jomar decided to unionize, Jose Pires was arrested by the police and was charged with assault and harassment. Several workers said that the incident was just another example of mistreatment by their bosses since they voted to unionize. As part of the retaliation, they said, employers also cut their work hours. Before the election, workers had 12-hour shifts; afterward, their shifts shrunk to six.

The abuses had gone on for years and, according to workers’ legal complaints, would continue many years afterward. The scale of the violations was immense.

Jomar was one of the carwashes included in a settlement totaling $3.9 million announced by then-attorney general Eric Schneiderman in 2014 for “widespread labor law violations, including underpayments, underreporting of employees on state unemployment insurance returns and failure to carry required workers’ compensation insurance for all employees.” The violations went from 2006 to 2012.

Years later, in October 2019, a worker named Roberto Alvarenga filed a class-action lawsuit in the Eastern District Court of New York claiming that a group of 20 to 30 Jomar workers toiled 72 hours a week or more without receiving overtime pay from 2016 to 2019, which constituted “a blatant violation” of the New York Labor Laws. The case was settled out of court in November 2020.

The struggles in Jomar went on for years, despite the evident asymmetry between the contenders. Jomar was part of two chains of 21 interrelated establishments in New York.

The vast majority of carwash workers are undocumented immigrants. According to a 2019 survey by the Center for Health and the Environment of The City University of New York, CUNY, 94% were born outside the United States, mainly in Mexico and Central America. Despite their status, these workers fueled a labor-rights movement that proved transformative.

Also Read: 12 Workers Make History Forming New York’s First Farmworkers Union

They voted to unionize in several carwashes across the city and pushed for a state law requiring car wash owners to pay at least the minimum wage ($15 per hour) and eliminate the so-called tip credit, which allowed employers to include gratuities in their wage calculations. The bill was signed into law in January 2020, and also benefited nail salon workers, hairdressers, aestheticians, valet parking attendants, door attendants, tow truck drivers, dog groomers, and tour guides.

The changes were advocated for by immigrant workers organized under the RWDSU along with the grassroots community organizations Make the Road New York and New York Communities for Change. “Part of the organizing is to improve the conditions and raise the floor for everybody in an industry,” Chelsea Connor, spokesperson of the RWDSU, told Documented. “In addition to the car washes that have union contracts, the non-unionized workers benefited from the advocates’ work as well.”

The law was necessary to protect all the car wash workers, including those in unions, which faced constant retaliation. In May 2017, 20 Latin American immigrant workers at Jomar went on strike to denounce a monthly-wage contract below the state minimum wage. Two years later, in May 2019, at least three of the company’s workers filed a complaint at the National Labor Relations Board, according to Freedom of Information Access’ documents obtained by Documented.

The workers accused the employer of retaliation by reducing their work hours “to discourage union activities.” Certain portions of the charges were deferred to an arbitration process and dismissed in May 2020, although the employers could still appeal. Jose Pires, Jomar’s owner, declined a request for comment.

Recent incidents of abuse are not exclusive to Jomar. In June 2021, a former employee filed a class-action lawsuit against Uniondale’s 5-Minute Express Car Wash in Long Island, alleging that he and some of his coworkers had worked for 70 hours a week or more for eight years without overtime pay.

Confronting exploitation

Car wash workers and advocates are confronting an industry that has grown on the back of overworked immigrants. As of 2019, the year for which the most recent figures are available, New York City registered 264 car washes that employed 2,420 workers. Many of the city’s establishments have incurred serious labor violations.

An analysis of OSHA data revealed that nearly all of the 38 inspections conducted in car washes in New York City from 2008 through 2013 found serious violations, with a mean of 2.5 per facility, according to an RWDSU report. Another report, issued in June 2015 by then Public Advocate Letitia James, revealed that 28 car washes violated state minimum wage and overtime laws.

Also Read: Essential Subway Workers Allege Underpayment and Dangerous Conditions

The exploitation translates into health problems. Car wash laborers worked on average 10.1 hours per day, with nearly one-half (43%) employed six days a week, according to the CUNY survey. During the 12 months prior to the survey, workers reported a high prevalence of ailments, including musculoskeletal pain (80%).

Automation taking jobs and unions

Despite the physical toll they pay, these workers have boosted the city’s carwash industry, which grew from 226 facilities in 2015 to 264 in 2019, the last year for which U.S. Census figures are available. The industry is also automating — adding more pressures to the workers’ struggle to a lawful pay. Car washes are using radio-frequency identification chips and license plate readers to detect recurrent customers, and incorporating sensors to gauge the size of a vehicle and automatically adjust the wash tunnel.

While the car washes multiplied in the City, the number of workers decreased. In Queens, the borough with the highest number of car wash establishments in New York, employers went from 958 in 2015 to 861 in 2019, even though the business count increased in the borough from 74 to 93 in those four years.

The job contraction speaks to the challenges faced by the City car wash workers and the labor movement. Despite RWDSU unionization efforts and the minimum wage law eliminating the so-called tip credit, evidence suggests that carwash workers are still underpaid and deprived of their lawful wages.

According to the online employment marketplace and recruitment platform ZipRecruiter, as of November 16, the average annual pay for a car wash worker in New York City was $27,807 a year or $13.37 per hour, assuming that the job was a regular position with eight-hour shifts for five days a week.

Still, those wages are below the $15 minimum wage guaranteed in a bill that car wash workers and advocates celebrated just last year. As in that night of 2013 when Jomar workers celebrated their unionization, that victory was temporary — one battle in a long term struggle. Jomar is still open for business, 24 hours a day.