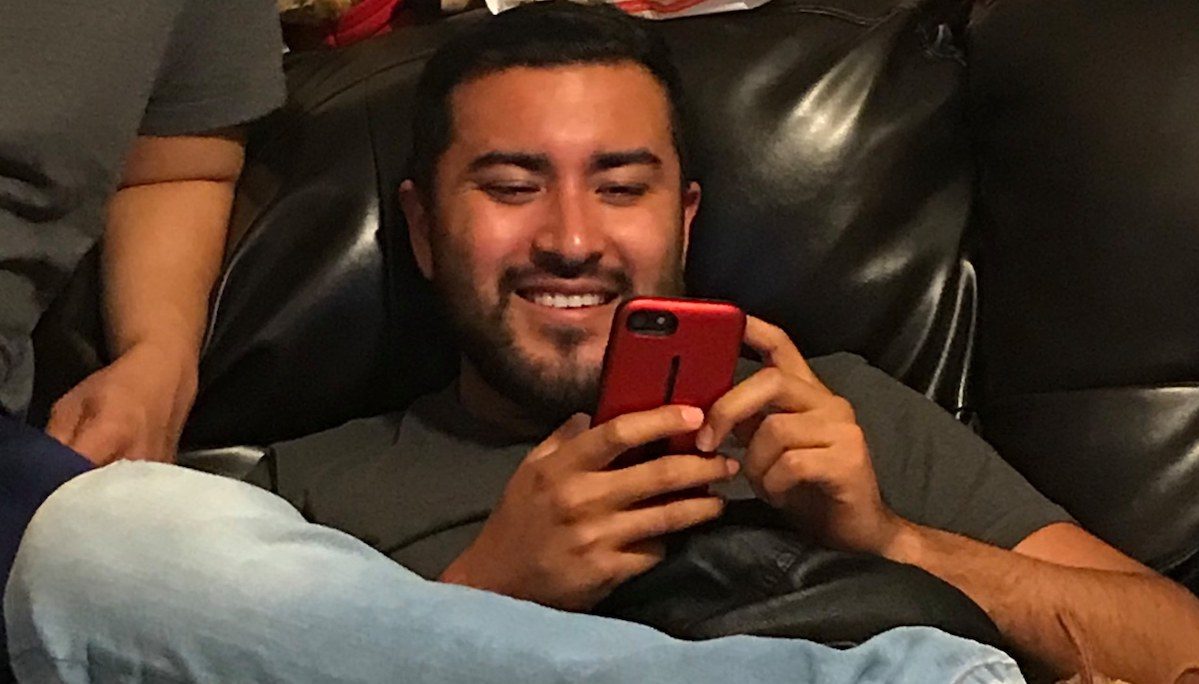

It was supposed to be a joyous reunion: Erick Díaz Cruz hadn’t seen his mother in more than a decade, since she left her native Mexico for New York. Instead, his visit became a nightmare when a confrontation with ICE officers at the family’s Brooklyn home resulted in an ICE officer shooting Díaz Cruz in the face. His mother’s partner, Gaspar Avendaño Hernández, was repeatedly tased and hit by pepper spray, according to court documents and various accounts of the shooting.

These circumstances on Feb. 6 2020 sparked community outrage, a criminal investigation of the incident, according to court records, and a civil suit against the U.S. government and the ICE agent who shot Díaz Cruz.

But more than two years later, the family feels as if justice is still out of reach. The case remains essentially on hold as U.S. authorities continue their investigation into what happened that day, according to court papers. “It’s hard to continue like this without knowing what’s going to happen tomorrow or how long this is all going to take,” Carmen Cruz, Erick Díaz Cruz’ mother, said in Spanish in a recent interview. “My son’s life, and all of our lives, are no longer the same.”

How We Covered It: An ICE Shooting and a ‘Political War of Words’

In February of 2020, Erick Díaz Cruz filed suit in Brooklyn federal court against Henry Santana, identified in court records as the ICE agent who shot him, for allegedly violating Diaz Cruz’s civil rights. The suit later added the U.S. government as a defendant.

Dara A. Olds, an Assistant U.S. Attorney at the Civil Division of the United States District Court, Eastern District of New York, who is representing the government, said at a hearing last July that a criminal case is potentially being brought against Santana, according to a transcript of the proceedings filed in court. Olds added that the Department of Homeland Security conducted an internal investigation, which was referred to the U.S. Attorney’s Office for a criminal probe, the transcript shows.

Meantime, the family has been left with mounting medical bills from the incident and deep uncertainty about whether they will remain in the United States or return to Mexico. To this day, they live in the same house where the shooting happened, Carmen said.

There are times where Carmen, 48, feels life has become so overwhelmingly difficult after the shooting that she thinks about moving back to her native Veracruz, Mexico, after living in the United States for more than two decades. Her son, Erick Díaz Cruz, remains in the United States on a valid tourist visa, for which he submitted extension requests and awaits the government’s response, his lawyer said. But he has not yet acquired work authorization in the United States, and left behind a job as the presiding assistant of the mayor of Martínez de la Torre, in Veracruz, Mexico, according to court documents.

“Everything has been lost,” Carmen said. “As a mother, I feel awful that this happened when he [Erick Díaz Cruz] came to visit me after 11 years without seeing each other.”

How the Erick Díaz Cruz shooting unfolded

On the morning of Feb. 6, 2020, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents arrived at Carmen’s home in Gravesend, Brooklyn, seeking to arrest her long-time partner, Avendaño Hernández.

Avendaño Hernández was leaving for work when the officers, dressed in civilian clothing, attempted to apprehend him outside his home, according to court documents and the family’s account. Avendaño Hernández said he did not know who the individuals were because they did not identify themselves, according to the family, and resisted. ICE officers tased him 15 to 20 times, court documents show.

Erick Díaz Cruz, now 28, came out of the house when he heard screaming and crying on the street, and the situation soon escalated, according to court documents. Díaz Cruz was shot from approximately four feet away, and the bullet went through his left hand, into his left cheek, and lodged behind his ear, according to a lawsuit Díaz Cruz has filed.

Neither Díaz Cruz nor Avendaño Hernández was armed.

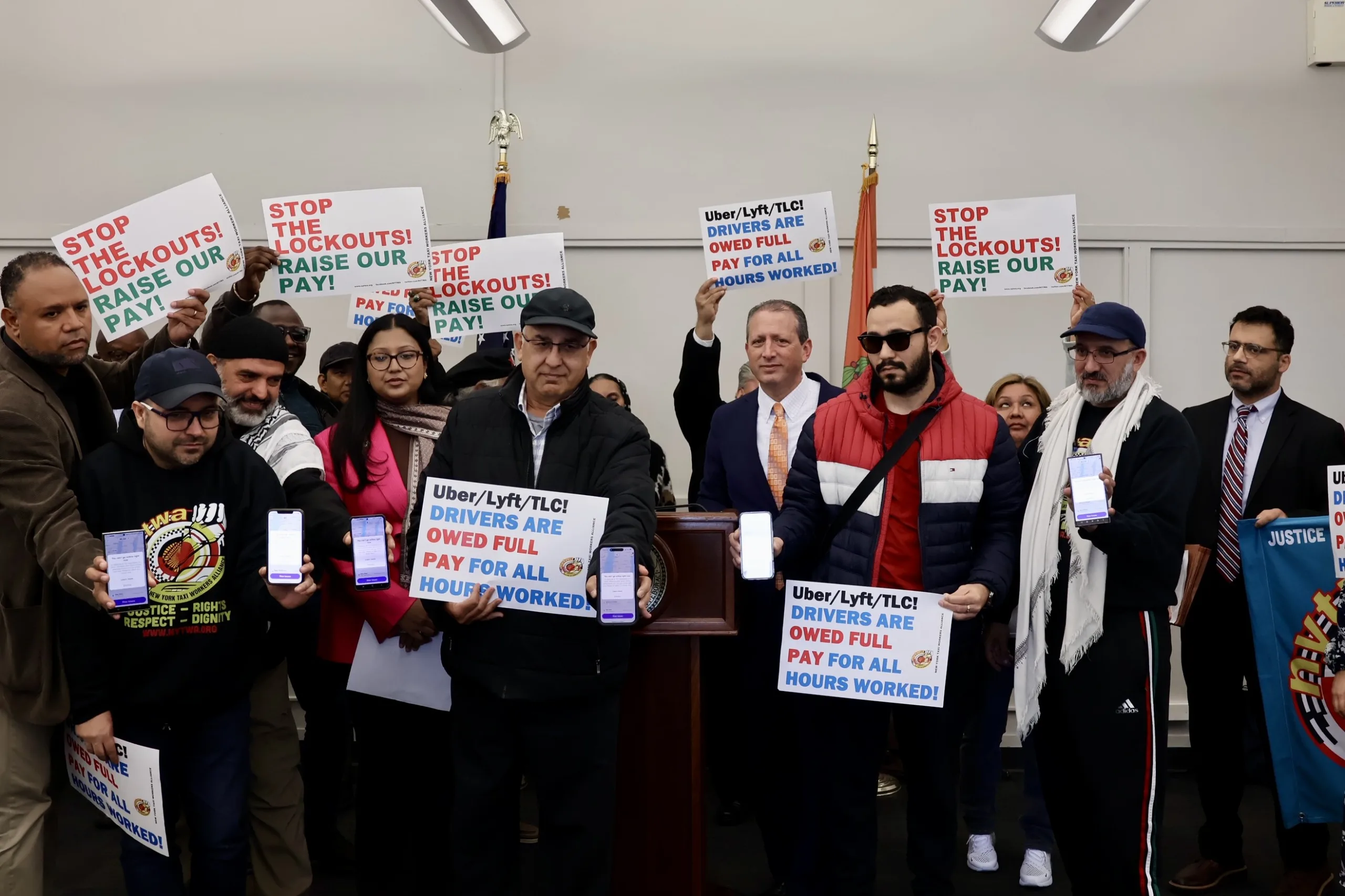

The shooting set off a political uproar among immigrant advocates and others, who condemned officers for what they called excessive use of force. The incident came in the same week as a State of the Union address in which then-President Donald Trump attacked New York for its policy of refusing to hand over to ICE undocumented immigrants in city custody.

After the incident, ICE shifted blame to the NYPD, saying that agents would not have had to visit Avendaño Hernández’s home if the police had turned him over to ICE after he was flagged in a traffic stop three days earlier, Documented previously reported.

Avendaño Hernández, now 35, had an assault conviction from 2011 and had previously been deported twice, ICE said in a widely reported statement at the time. But he had returned to the United States and was arrested a few days before the shooting after he was stopped for driving without a license, not having proper license plates, and not signaling a turn, the New York Times reported. He was then released and returned home, but his arrest alerted ICE to his presence.

Avendaño Hernández was free on Feb. 6, when ICE agents arrived at the family home in Brooklyn. Their intention was to take Avendaño Hernández away for deportation back to Mexico. But the seemingly routine detention case soon turned violent.

After the shooting, both Díaz Cruz and Avendaño Hernández were taken to Maimonides Medical Center in Borough Park, Brooklyn. At the hospital after being tased, Avendaño Hernández was diagnosed with a cardiac irregularity — “an interruption or alteration of the electrical conduction of the heart,” Judge Paul Oetken said in a ruling.

Marie DeLuca, a New York City emergency medicine physician, testified at a city council hearing in February of 2020 that Avendaño Hernández did not previously have a history of heart problems – but after he was tased, she said, he had multiple abnormal heart tests.

Avendaño Hernández was sent to the Hudson County Jail after being released from the hospital, but in the spring of 2020 was granted emergency release from the correctional facility because of Covid-19 and health conditions he was diagnosed with after he was tased. The family has been unable to pay for some of Avendaño Hernández’s follow-up treatment and examination, Carmen said.

Avendaño Hernández had previously filed a habeas petition against ICE, which contests his detention. The petition raised several arguments, including that he had a heightened risk of contracting a serious COVID-19 infection while detained and that he needed to be released to secure adequate medical attention, said Natali Soto, an attorney with the Immigration Practice at Brooklyn Defender Services, who is representing Avendaño Hernández. The petition is still pending, almost two years after it was filed.

Díaz Cruz lived with the bullet in his face for about five months, until physicians determined that it was safe to extract the projectile. He has lost mobility in his left hand and arm, and vision in his left eye, according to the lawsuit he filed against ICE. Díaz Cruz has had multiple surgeries to deal with the injury, and is often having check ups with doctors, his mother said in a recent interview.

Since the incident, the family has also been struggling economically, Carmen said. They are behind on rent, and Carmen hasn’t been able to find employment since she lost her job last year at a hair salon where she had worked for more than 20 years. Her partner, Avendaño Hernández, works in construction and is the only person in the household who is currently employed.

Avendaño Hernández, Carmen said, is “working, battling for us, to move forward.”

Díaz Cruz had not seen his mother in 11 years when he arrived in Brooklyn and was visiting her in the United States on a tourist visa when the shooting took place, his family said. But he now seeks to remain in the United States to continue his medical treatment, said Gabriel Harvis, his attorney.

Still, he longs to go home to Mexico soon, his mother said – though his legal team is concerned that if Díaz Cruz returns to his home country, he won’t be allowed back into the United States, despite his pending lawsuit against the government and the agent who shot him.

Avendaño Hernández lives in Brooklyn with his partner, Carmen, and Díaz Cruz, and continues to wear an ICE electronic tracking ankle bracelet, Carmen said. His removal proceedings – to determine if Avendaño Hernández will be able to stay in the United States – are pending, said Soto, his attorney. An upcoming court date for the proceedings is scheduled for early September.

“Our hope is that Mr. Avendaño Hernández will be able to live free of the fear of deportation and continue to seek the medical attention he needs,” Soto said. “We hope those responsible for the events that transpired during our client’s ICE arrest will be held accountable.”

The legal battle continues

In his lawsuit, Erick Díaz Cruz is seeking unspecified monetary damages for what he calls an improper shooting.

In a response to Díaz Cruz’s complaint filed in court, Santana, the ICE agent, acknowledged firing his weapon, but his defense wrote that “to the extent that any force was used, such force was reasonable, necessary, and justified,” according to court documents. Santana denied many of the allegations brought against him, including that his actions in shooting Díaz Cruz were “unreasonable and excessive,” court documents show.

At a hearing in federal court last July on the civil suit filed by Díaz Cruz, Elizabeth Wolstein, an attorney for Santana, said that Díaz Cruz “beat up on” the ICE agent and “pounded” him in the face, according to the court transcript. Santana suffered a concussion, orbital, and corneal injuries, Wolstein said, according to the transcript.

But Díaz Cruz’s legal team refutes these claims. “We deny and dispute that Erick committed any acts of violence towards Santana,” Harvis said in an interview.

On Jan. 12, the federal judge presiding over the case, Judge Sanket J. Bulsara, granted a motion submitted by the government to continue a stay of discovery. This blocks both sides from making requests or demanding information from one another, Harvis said. The reason for the stay, according to court records, is the pending criminal investigation into the February 2020 incidents.

The Department of Homeland Security’s Office of the Inspector General has been working with the Criminal Division of the U.S. Attorney’s Office, Eastern District of New York, to investigate the shooting, according to a letter dated Jan. 3, 2022, court records show. As of early January, the investigation remains ongoing, according to the letter submitted in court.

For Díaz Cruz’s family and their legal team, the delays in the case have been excruciating. “It does seem like a really long time to try to figure out whether there was a crime committed here or not,” said Harvis, the attorney for Díaz Cruz.

He added: “We respect the position of the government, but we are also growing increasingly frustrated with the amount of time it’s taking for the Justice Department to decide whether or not they’re going to bring charges against Santana, which we obviously believe are warranted.”

John Marzulli, the Public Information Officer for the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of New York, declined to comment on the case. Attorneys for Santana did not respond to request for comment. A spokesperson for the Department of Homeland Security, Office of the Inspector General, said that the agency does not comment on investigative matters, to “protect the integrity” of their work.

ICE declined to comment due to the ongoing investigation surrounding the incident by the Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General.

Carmen recalls the day of the shooting with sorrow and regret. She and her son had not seen each other since she left Mexico for the United States more than 10 years earlier. But the violence of Feb. 6, 2020, obliterated what had been a long-anticipated reunification. “We never imagined a tragedy like this,” she said. “He was happy to come see me, I was happy to welcome him.”

Now, the family wonders if there will ever be any sense of accountability. “I don’t want any more families to go through what my family went through,” she said. She voices the hope that one day, “justice will be carried out.”