The last interaction Eva Zhao, 37, had with her husband, Zhiwen Yan, 45, was on April 30th at 6:30 p.m. when he dropped her off at home from the laundromat in Forest Hills that they ran together. He left with his scooter to continue his shift as a delivery worker at Great Wall restaurant in Queens Boulevard, where he had done deliveries for over 15 years.

Three hours later he was shot half a mile away from the restaurant while waiting for a traffic light.

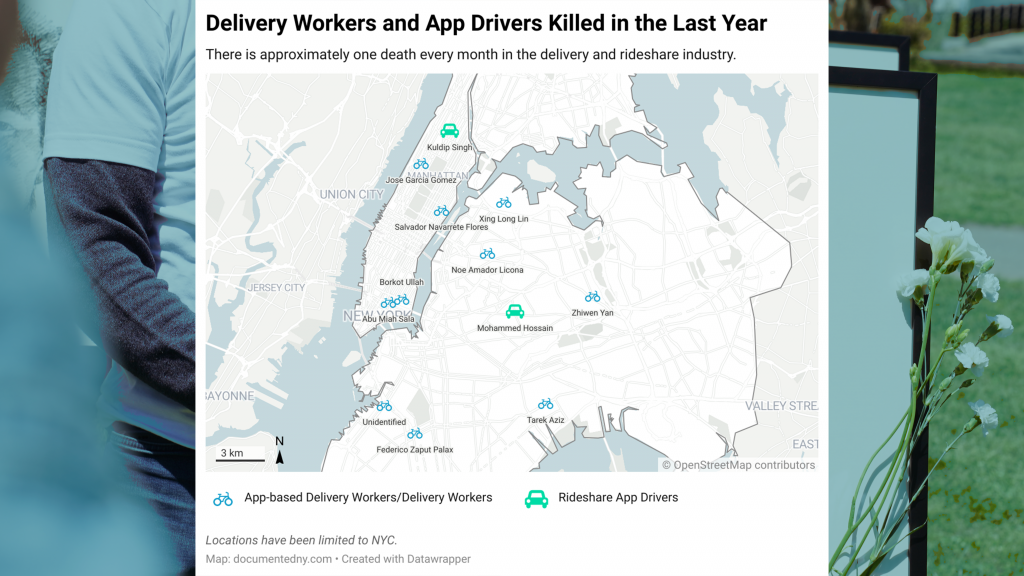

Yan is one of two delivery workers who have died while on the job in the span of a week. There is approximately one death every month in the delivery and rideshare industry. According to a report released by Workers’ Justice Project and The Worker Institute of Cornell University’s ILR School, 54% percent of the delivery workers surveyed reported having experienced bike theft, with 30% of these saying that they were physically assaulted during the robbery.

Zhao alleges that her husband had been robbed at least two times and had lost several E-bikes due to theft. “Delivery work is very risky,” she said.

The deaths and injuries have raised concerns in workers who resorted to the industry after they lost their job during the pandemic. They say that they feel unsafe on the job and that app companies like Uber, Lyft and DoorDash have come short in offering their delivery workers protections and compensation for tragic accidents.

Also Read: Immigrant Delivery Workers Organize To Fight Rampant E-Bike Theft

Zhao said that Yan had worked extensively delivering 15 hours for UberEats, the Great Wall restaurant, and also at the laundromat daily. “Nobody in the world was more hard-working than him. He was working to make money for the children’s tuition,” Zhao told Documented.

With help of local Queens residents, Zhao had one GoFundMe page setup for Yan’s funeral, and another for donations to help the family. Both have received a total of over $300,000 in donations. “These donations are just a drop in the bucket, considering the family has a long way to go,” said Hailing Chen and Andy Chen, two Queens community advocates who helped Zhao set up the GoFundMe page, adding that Yan leaves behind three children ages 2, 14 and 15.

There are 65,000 app-based delivery workers in NYC, according to The NYC Department of Consumer and Worker Protection, the agency in charge of enforcing the laws protecting the workers. Because of their status as independent contractors, app-based delivery workers do not qualify for compensation or protections given to regular employees under the federal labor law, said Dachuan Nie, president of the International Alliance of Delivery Workers, one of the nine organizations part of the new coalition Justice for App Workers (JFAW) which represents more than 100,000 New York rideshare drivers and delivery workers.

“Usually for app drivers, they can receive compensation from Black Car Fund if accidents happen. But the fund does not cover UberEats drivers,” Nie added, referring to the New York State Black Car Fund which protects New York’s for-hire drivers, and can award a one-time payment of up to $50,000 to help people recover from tragedy.

Hailing Chen, who drove 6 years for Uber, told Documented that he helped an Uber driver’s widow and child file claims after the driver passed away on the job. On top of the 50,000 provided by the Black Car Fund, Chen explained the driver’s family were eligible to receive $12,500 for funeral costs and 2/3 of the deceased’s average-weekly-salary, in accordance with the New York State Workers’ Compensation Law.

Catch-22

Last April, Darrel Johnson, 34, a Brooklyn native, says he accepted a notification to pick up a passenger from Coney Island, one of the areas he frequented since he started driving for Uber and Lyft in 2016. At the location he was met with seven passengers. His SUV could only fit six passengers, as listed under UberXL’s guidelines, so he told the passenger that he would decline the trip.

One of the passengers approached him and took out a gun, pointing it at his chest, demanding Johnson to take the crowd in his car. Johnson says he started pleading for his life — telling the passenger that he had a daughter and a wife to return to. The passenger made jokes about him before letting him go. “At no point in time did I anticipate that this job would be dangerous,” he added.

Lured by the flexibility that the job offers, Johnson, who has two bachelor’s degrees, thought his ride in the industry would be temporary. But the lack of opportunities in other sectors has kept him working as an independent contractor. In April 2020, due to the coronavirus, he stopped working for four months and returned to the road after his savings depleted.

Five months after the incident at Coney Island, Johnson had another encounter with a passenger who wanted to take a crowd of seven in his car. According to the driver, the passenger cursed at him, threw alcohol on his face and inside his car.

Also Read: Delivery Workers Are Struggling to Survive the Pandemic

Johnson says that if he had died of the coronavirus in 2020, or had been killed, his family would have been financially burdened. “Do you know how much a funeral costs?,” Johnson asked. He says he purchased life insurance so that he can leave his family with a financial backing if something were to happen to him.

Johnson submitted a report for both incidents to Uber and the NYPD, but says no apprehensions were made.

Hector German, a member of UTANY, a taxi driver union in New York, says that his organization hears of at least six complaints of assaults every week with many drivers being robbed of their earnings.

“The app companies took complete control of the industry by tempting New Yorkers with sign up bonuses, and now they work without any protections. Its profit over the safety of the driver,” he said.

Protections for app-users but not for drivers and delivery workers

Fear of crime and concern for their safety spread among app workers. Nie said in some WeChat groups consisting of Chinese delivery workers or app drivers, members share real-time information about crimes and pay close attention to the updates on the Citizen app. The app sends users location-based safety alerts in real time.

Nie noted that many drivers avoid taking rides “in some dangerous neighborhoods.”

During a memorial event held at Inwood Hill Park on May 10th to remember the life of app-based workers who had died while on the job, 12 drawn portraits of the victims were placed at an area known as the Tree of Peace. Attendees, consisting of advocates, family members, and friends, called for better delivery workers protections and safety for drivers.

JFAW called for a better in-app alert system that allows victims to work directly with the police and demanded apps to provide financial compensation for workers and their loved ones. “Violence against drivers and delivery workers is on the rise, and it’s terrifying. App companies and our City and State leaders need to address this safety crisis before we lose another member of our community,” a spokesperson for the coalition said about protections for delivery workers.

App workers, like Johnson, demand that app companies no longer enable customers to use fake names — a practice which makes incidents hard to track — and ensure all vehicles are equipped with dash cameras.

“All Dashers are covered by our occupational accident insurance at no cost to them and with no opt-in required. While negative incidents are extremely rare, we’re constantly working to better protect and support Dashers in New York City,” a spokesperson for DoorDash told Documented, adding that “DoorDash has zero tolerance for harassment or discrimination of any kind and we take all reports extremely seriously. Anyone found to have violated our strict policies faces immediate removal from our platform.”

Documented learned that Lyft’s safety team can work with drivers and families of drivers to provide assistance as needed, including financial support, depending on the circumstance of the case.

As of date of publication Uber did not respond to Documented’s request to comment.