If you arrived in New York City without any connections, could you find a place to sleep tonight? As thousands of migrants arrive in New York City on buses sent by the state of Texas, they need information about how to settle into their new city – and many are coming to our journalists on WhatsApp to get answers.

Starting in late July, Rommel Ojeda noticed that more requests were coming in through the Documented WhatsApp channel from people seeking food and shelter. The number of people in that community increased sharply – about 400 new users started following the newsroom this summer, and Ojeda estimates that 60% of them are asylum seekers in local shelters or on their way to NYC.

As Documented’s Latino community correspondent, Ojeda has adapted our newsroom’s community engagement strategy to meet the needs of these new arrivals. The Documented Whatsapp community is a space where immigrants, most of whom are undocumented, can speak directly to a Documented reporter.

That space was developed during the early days of the pandemic as a way to quickly reach our readers who had immediate concerns for their health, safety, and financial wellbeing. Based on those recurring concerns and questions, we created a library of resources that details how immigrants can find everything from legal help to language classes. We are seeing similar challenges surface again as newly arrived migrants reach out to our newsroom. Ojeda has tailored recent editions of Documented Semanal, the Spanish newsletter we send over WhatsApp, to respond to the concerns he’s receiving from readers who are asylum seekers.

Based on their questions, we recently wrote guides about the NYC shelter system, how to contact Latin-American embassies, and how to obtain a green card as an undocumented immigrant. By communicating with asylum seekers at the grassroots level, we were also able to write about the failures of the NYC shelter system.

Through your daily communication asylum seekers, what are you learning about their struggles?

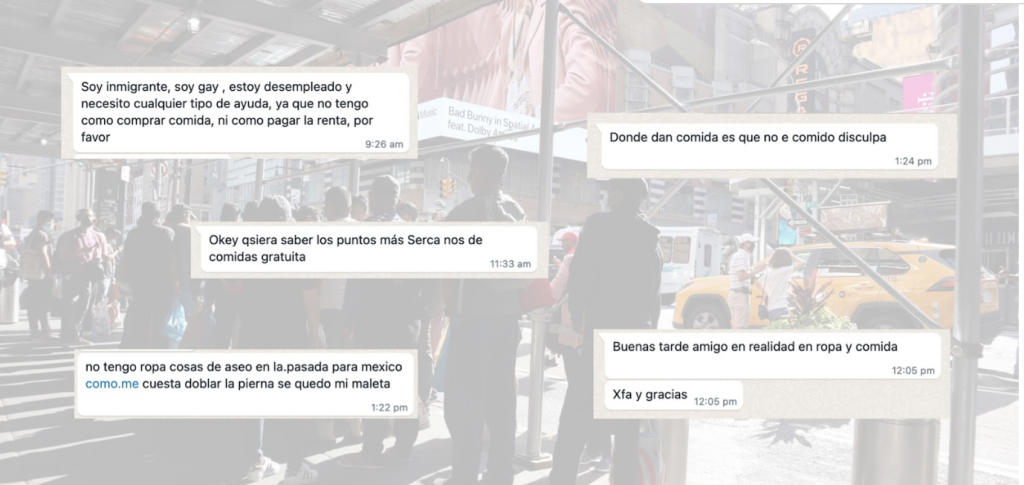

Rommel Ojeda: On average, we used to receive around 30-40 messages via WhatsApp daily, in which we would follow through with detailed conversations. Now, we get about 60 daily and we hold many of those conversations with asylum seekers.

With Documented on WhatsApp, people send messages directly to us. We don’t put them in a group because a lot of the information shared is private and sensitive, so our communication is 1 on 1 encrypted in the chat, and it can only be seen by me. This has helped us build trust. What they can do through there is request resources, share complaints, which we might use to create stories or delve into investigations. For most of them, it is an open line where they can talk to a journalist and get a response within a couple hours if not instantly.

When people reach out to us, it’s usually in this sequence: they request information about shelters, food, and clothing. Once that is taken care of, although not always possible, then they start requesting assistance for finding pro-bono legal services, housing, and employment.

There are people in NYC who do not want to be here. I heard from a few people who, because there were no translators when they were released from detention, they did not even know they were coming.

We are also hearing that lack of translators at shelters has been very detrimental. For example this person who is pregnant at the shelter was feeling sick, and she couldn’t communicate with the personnel at the shelter. She had to contact a mutual aid group who took her to the ER. Those scenarios show that there needs to be something done in terms of addressing the language barriers.

I think the coverage around asylum seekers is resurfacing the issues that we already had in New York. There has always been a need for food pantries in our immigrant communities, which is what has been requested by many asylum seekers who feel that the food at the shelters are not nutritious and often cold. They have, also, specifically requested soup kitchen locations because they are not allowed to take raw food to the shelters.

To access pandemic programs, New Yorkers needed passports, ITIN Numbers, IDNYC, and/or a driver’s license. Now, because asylum seekers had their identification documents taken away when they were detained, they are struggling to access city programs or obtain proper identification that could give them, for example, access to fair-fare Metrocards.

We have been updating our consulate lists with contacts, and IDNYC guides with the most current information so that new immigrants could start applying for their identification documents.

The biggest thing requested, which I don’t have an answer to, is how to find work? That’s something that’s going to come up more with time as they get their asylum cases moving.

How is community engagement central to your work as a journalist?

There are two ways asylum seekers are being covered. There are the immediate headlines about how many people are coming on buses and where they are going, and also the political turmoil between Texas and blue states. The other way to cover them is to find practical answers to the needs they are facing. Thankfully, we have already been doing this type of work.

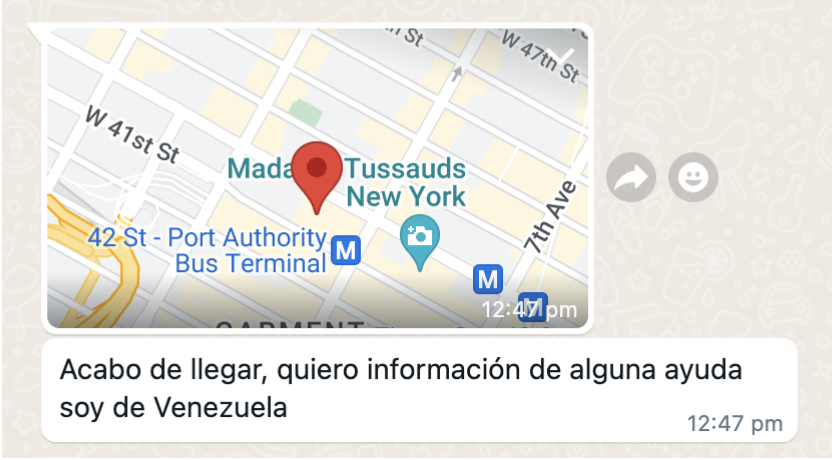

When they reach out to us, they have arrived in NYC and they don’t know where to go or what to do to find a place to stay. Some people have shared their live location with us because they are bussed into a new city that they may or may not have intended to travel to. Over the past 3 weeks, we have gotten at least 50 questions about how to access a shelter. The more comments we got, we saw there was a necessity to create a guide to finding shelter.

Trying to serve our community and our audience is what has always been a priority. My job as community correspondent is to be present in the community to see what their needs are, and then I can produce actionable content that can address the needs of those who contacted us, but also the needs of those who will contact us in the future.

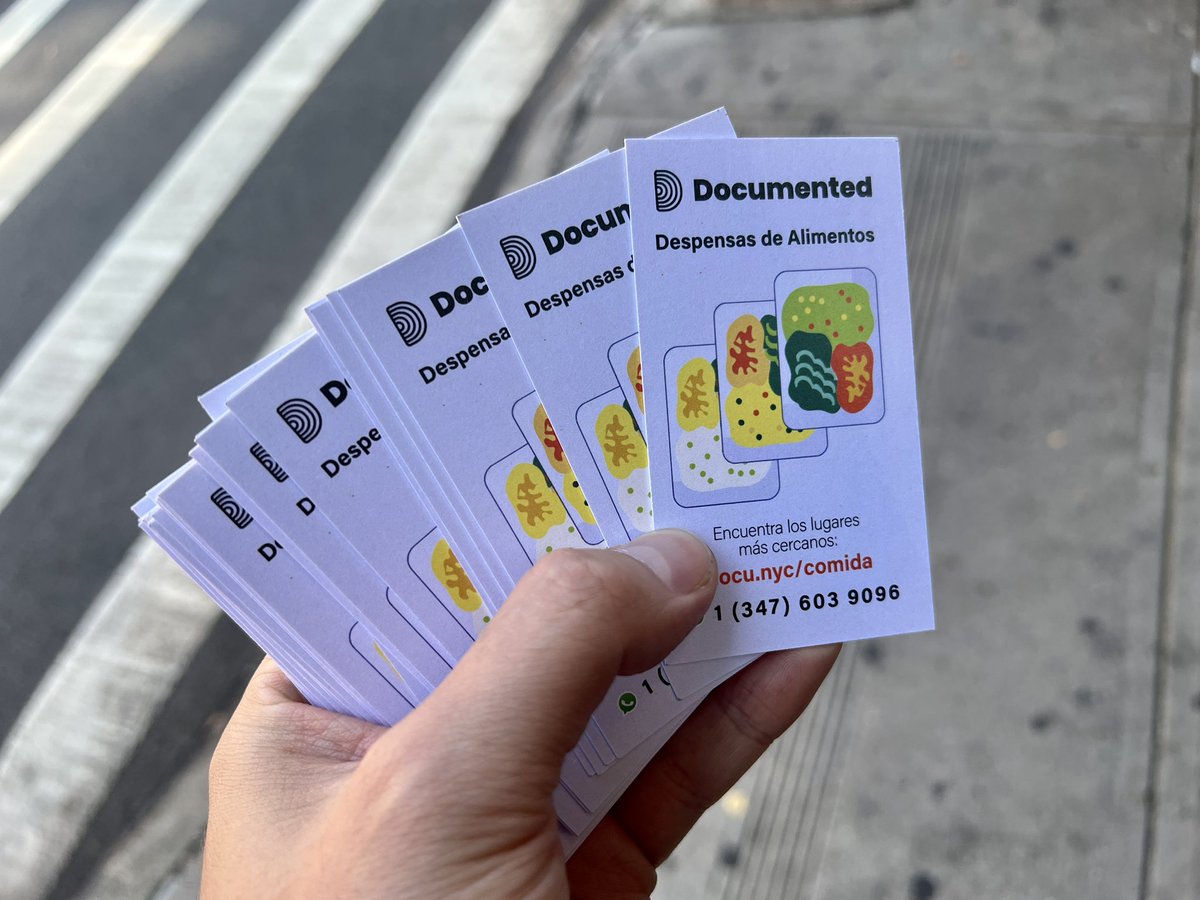

We have also dropped off some flyers with our list to food pantries at the men’s intake shelter at 30th Street. I introduced myself and told them that they could contact Documented via WhatsApp. We started to receive messages the same day. We had also received messages from other asylum seekers at the shelter who had heard it through word of mouth. Some local organizations and mutual aids also helped us distribute some of the flyers. We even had three cases when people had sent a photo [of our newsroom contact information] to some of their friends making their way to the states from Mexico.

The more we communicate with them, the more trust we are building. If we can have a community that trusts us, they will come to us for resources and also tell us the problems that are happening in the shelter system, which dictates the stories we should be writing.

At the end of the day, journalists are not social workers. We are not supposed to be involved to a certain degree, so if we can find a trustworthy organization, connecting them is the service we can provide to somebody. In a way, my work for the past three weeks has been getting in touch with these organizations and finding the most practical information that we can provide to the people that reach out to us. The response of the organizations has been reassuring to see, they are providing immediate resources to take care of urgent necessities to get these people started.

What do you wish Documented’s other readers understood about incoming asylum seekers?

It’s important to understand that the problems migrants are facing in NYC are problems that have been happening for a while. Right now, it’s been covered by so many outlets that don’t focus on immigration, but we are an immigration newsroom, and we know this has been happening for years. Our resource guide is a product of those problems because it addresses the needs of the people.

I’m proud of the work we’ve been doing here. Immigration has been our beat since we started Documented, and we have covered many of the things that are now coming up on the news again. Immigrants face barriers that have been in place for decades, due to systems and programs that have neglected certain communities.

Also Read: How Our Community-Oriented Approach Grew our News Audience