Twenty-three new immigration judges were appointed last week to immigration courts in nine states, including two new judges in New York.

Judge Brian Counihan was appointed to New York’s Batavia Immigration Court outside Buffalo, and Judge Themistoklis Aliferis was appointed to the Varick Immigration Court on Hudson Street in the City. They are set to begin hearing cases this month. Both have history working with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Counihan was an assistant chief counsel and deputy chief counsel with ICE’s Office of the Principal Legal Advisor for about 12 years in New York. He was among the highest-paid employees of the institution in 2017, according to FederalPay.org. Before working with ICE, Counihan was a special assistant to the U.S. Attorney for the Western District of New York.

Aliferis also worked with ICE’s Office of the Principal Legal Advisor for about five years in Miami. For 10 years before that, he practiced law independently and represented immigrants before immigration courts and the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

More about the portfolio and work history of all appointed 23 judges was published in the announcement from the Department of Justice’s Executive Office for Immigration Review on Monday.

A budget and hiring failure

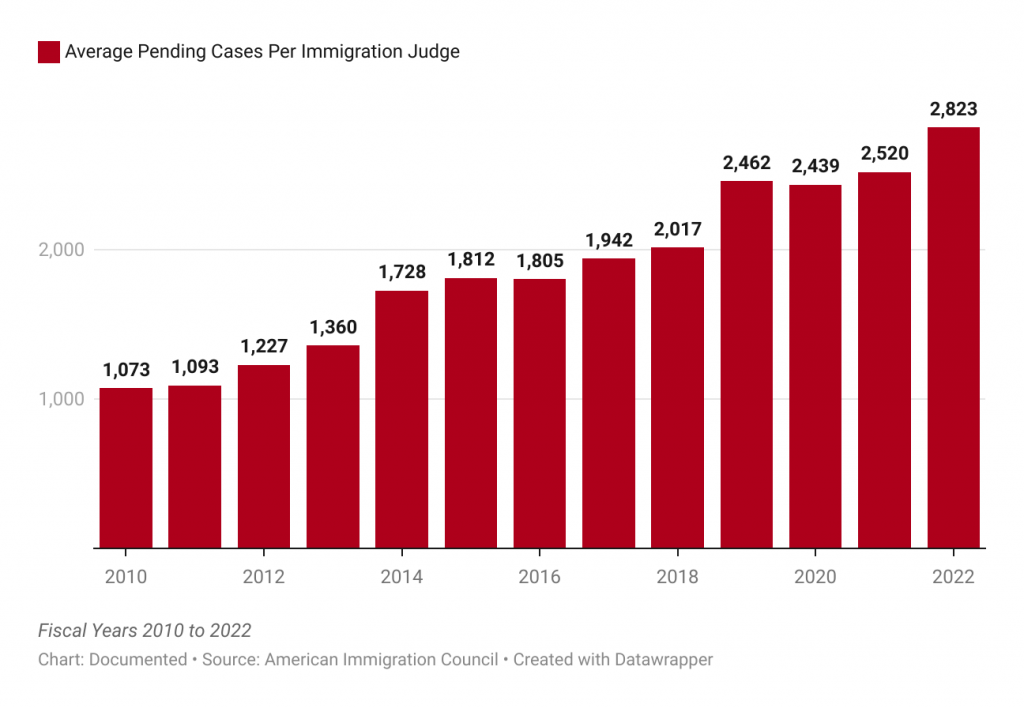

The federal government has been hiring more immigration judges on an annual basis since 2015, with 2021 being the exception. Last year was the first time more than 100 new judges were appointed to the immigration court. Still, this increase pales in comparison to the number of pending immigration court cases, which have skyrocketed since 2010, according to the American Immigration Council.

While the federal government keeps hiring new judges, it hasn’t been enough to create a big drop in the backlog of immigration cases. Cases have piled up because of an increase in the number of cases filed by the Department of Homeland Security, as well as the shutdown of many immigration courts during the pandemic.

Hiring more judges is important, but without the staffing to go along with them, judges can’t perform efficiently, said Samuel Cole, the executive vice president of the National Association of Immigration Judges.

“EOIR has not hired the judge teams that Congress directed them to. Judges are supposed to be hired with other staff, such as legal systems law clerks so that the judges can actually hear the cases quickly,” he told Documented.

The backlog shows again why the federal immigration system can’t keep increasing front-end enforcement without sufficient funding for back-end adjudication, Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, policy director at American Immigration Council, explained in a tweet last year. In the last 20 years, the Border Patrol’s annual budget has grown by $3.6 billion, compared to $568 million growth in the immigration court’s budget, Reichlin-Melnick said. Essentially, Border Patrol’s budget has grown six times more than immigration courts’.

However, Cole says he doesn’t think the lack of staffing in immigration courts is an issue of funding.

“I think it’s just an issue of management,” Cole said. “I think the way the immigration courts are run by the Department of Justice is very inefficient. And you have a court system buried in a law enforcement agency, and it doesn’t get the attention.”

When the EOIR hires new immigration judges, there is media attention, as the big announcements come with press releases — just like last week. But while judges are trying to fight the backlog, “the reality is the hiring of judges loses a lot of its importance if the support staff is not there with the judge,” Cole said.

In Chicago, where Cole serves as an immigration judge, there are over 93,000 pending cases — that total increased by more than 100% from 2s019 to date. For the period covering fiscal years 2017 through 2022, Cole decided on 501 asylum claims. But more staffers likely would’ve let him work through more case.

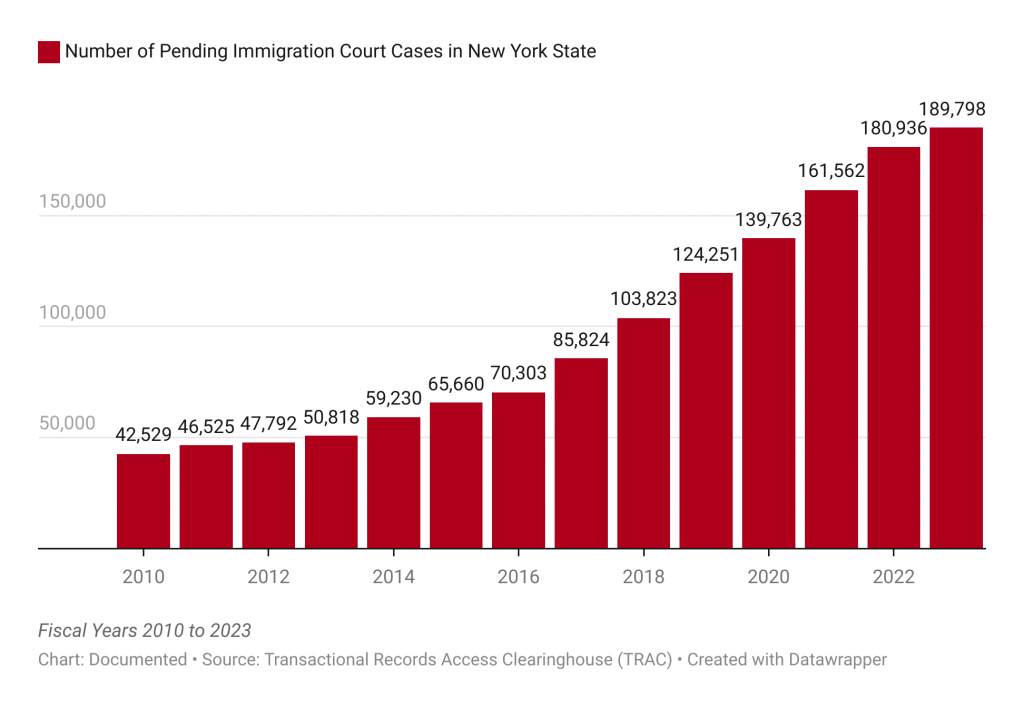

New York is ranked seventh among the top ten states with the longest average wait times in the immigration courts. Some migrants have had to wait for more than three years for a chance to stand in front of a judge. There are close to 190,000 pending cases in New York, and cases have increased 53% from 2019 to date.

Recent data (through December 2022) from Syracuse University’s TRAC shows that there are over two million deportation cases pending in immigration courts. If the backlog were a city, it would be the fifth largest in the country, just after Houston, TRAC analysis noted.

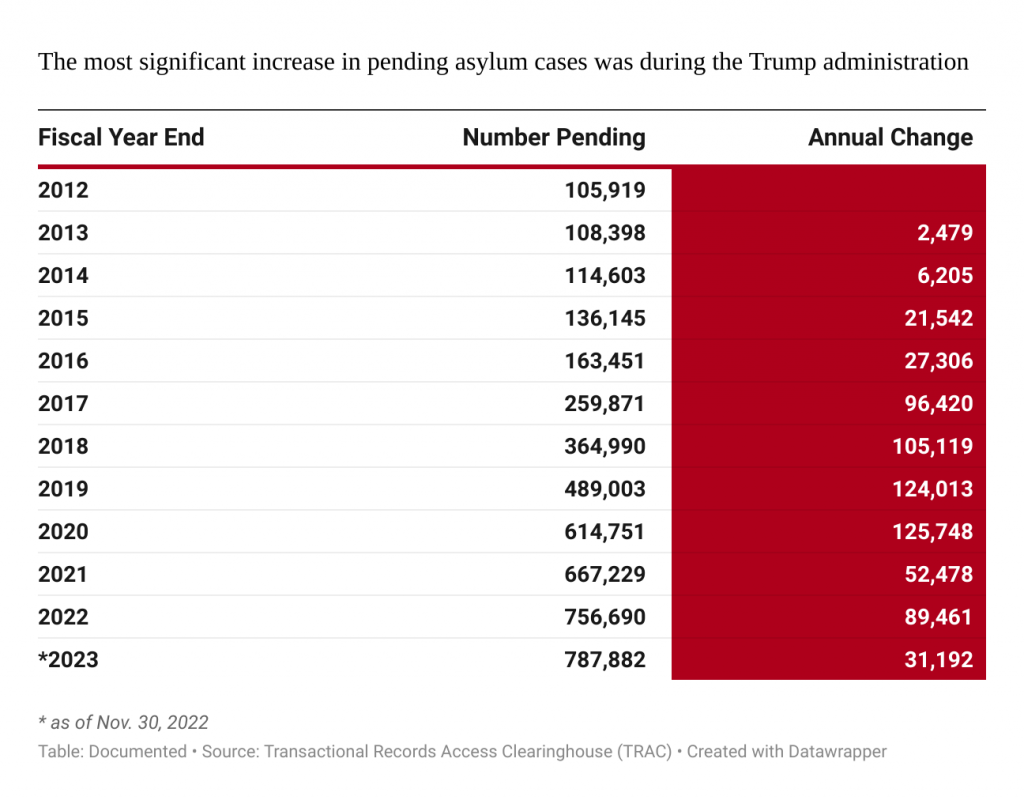

The most significant increase in pending cases was during the Trump administration, when border enforcement policies were the most stringent.

Balanced hiring is key

There are approximately 600 immigration judges in the country, and as of November 2022, there were 88 in New York state.

Among this new hiring class of 23, there are seven former ICE attorneys — which is not rare. Back in 2018, when the EOIR announced a new hiring class of 46 judges, there were 19 former ICE attorneys. That same year, the EOIR announced 16 judges in November, among which 10 had worked for the ICE Office of Chief Counsel. In New York state, more than 20 immigration judges worked for ICE.

These scenarios are a telling example of the need for balanced hiring, which immigrant rights’ advocates and experts agree on. But they also express the importance of having judges with prior immigration experience.

“Good judges come from a variety of backgrounds,” explains Cole. “There’s no one model of the right experience for a judge,” he told Documented.

“I actually think that when someone has prior immigration experience, they might be able to hit the ground running a little bit quicker because they’re used to the immigration issues,” he said. “But it really doesn’t mean that they’re going to be more pro-government.”

Allan Wernick, director of CUNY Citizenship Now, a free citizenship and immigration service project, also told Documented: “I’m not much concerned about a judge’s background. People change. The most hated judge I have heard of I met when in law school was a far-left Marxist. Another who came from private practice is among the most restrictive. Some of the most generous have been former trial attorneys.”

This story was updated on Feb. 14 to correct “legal systems law clerks” to “legal assistants and law clerks.”