Shekar Krishnan made history in 2021 when he became the first-ever elected Indian American New York City councilmember. Krishnan, the son of Indian immigrants from Kerala, secured a victory in District 25 of Queens, representing the Jackson Heights and Elmhurst neighborhoods. The district is home to a significant immigrant population, with a large number of residents hailing from the AAPI community.

Also Read: Where to Celebrate AAPI Heritage Month Events in New York

As May marks AAPI Heritage Month, Documented took the opportunity to speak with Councilmember Krishnan about how his AAPI heritage has influenced his political journey, how he intends to celebrate the month, and his vision for the AAPI community in Queens.

April Xu: As the first Indian American city councilmember in NYC, what motivated you to enter politics, and what has been your experience as an Indian American elected official?

Councilmember Krishnan: I ran because I know how important it is for everyone to have a home. And I know that because before I came into political office, I was a civil rights lawyer for a long time, representing tenants, many who are immigrants. I’m focused on housing discrimination and displacement, and I’ve always said housing is the most urgent crisis we face because it connects to every other crisis around us.

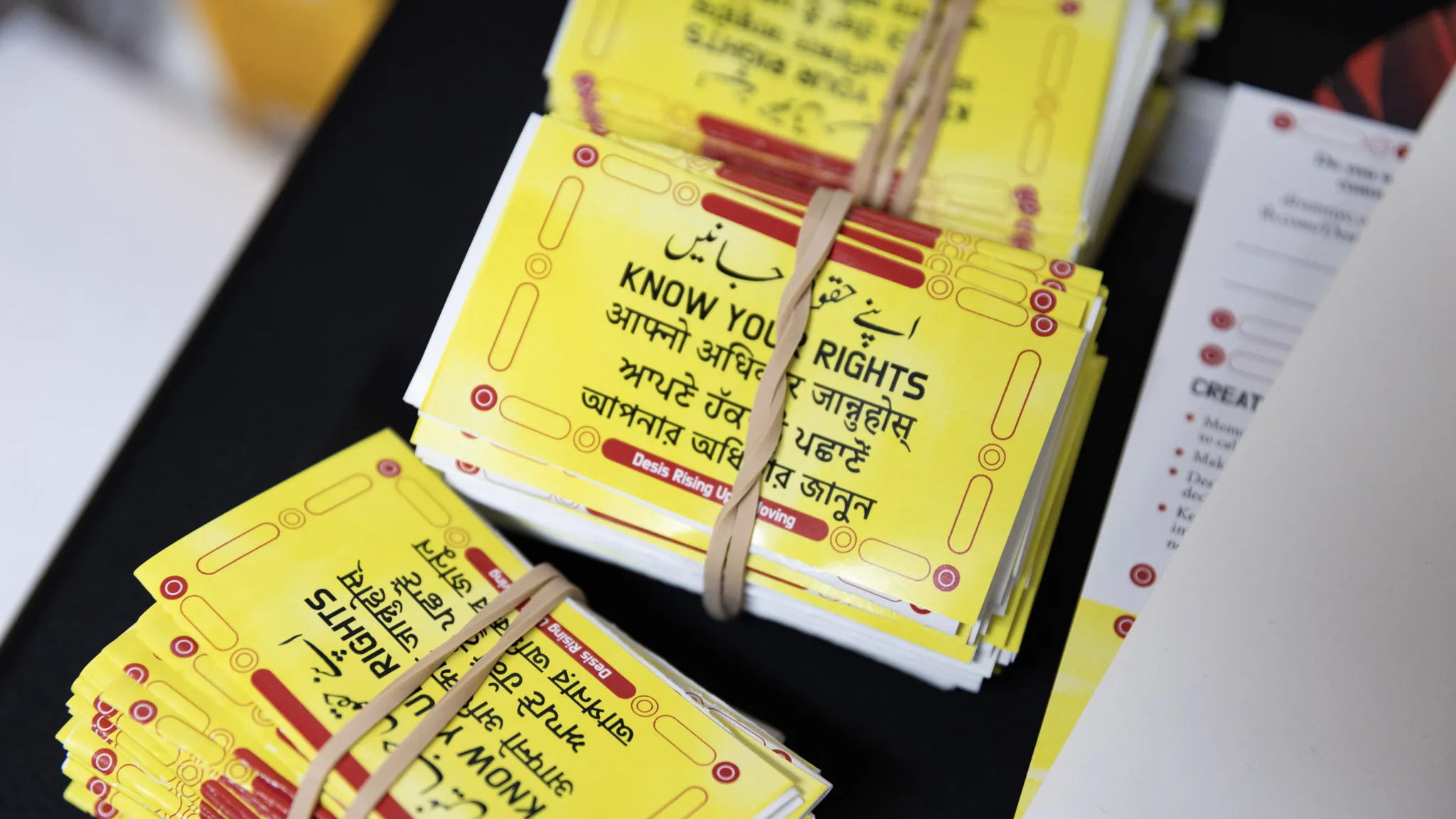

That’s especially true in Jackson Heights and Elmhurst because all of these problems are magnified throughout immigrant communities. You see the way in which so many of our Asian American communities, our immigrant communities, are without a voice in government. So often their concerns are not heard — we don’t receive resources from the government in our languages, which means that our rights aren’t protected. So that’s what motivated me to run, and that’s why it’s so important that we have representation from our communities in office. I’m so proud to be the first Indian American ever to join City Council, and to do so from Jackson Heights and Elmhurst, which are two of the most diverse communities in the world.

You have been involved with the AAPI community in Queens for many years. What changes have you seen in the community in the past few decades, and what needs do you see within the AAPI community you represent?

What I’ve seen over the last couple of decades is the way in which our Asian American communities in Queens have only grown and become even more of an essential part of the fabric of New York City. We’ve grown and we’ve gotten much bigger as a percentage of the population in New York City. But also, the needs of our communities are increasingly urgent, and they haven’t been met; whether it’s making sure that our communities have access to health care that we desperately need, whether it’s language-accessible services for our small businesses, whether it’s support for our immigrant workers like our taxi workers.

As we’ve grown in population, and ever more so as our presence and political power in New York City has grown, so have the big issues affecting our community, like the high rates of poverty in our community. So, it’s even more urgent that our city address those issues in the AAPI community.

What is your vision for the AAPI community in Queens and New York City to move forward and how can the City Council support and uplift this community?

My vision is that our AAPI community is finally seen and heard. For far too long, we’ve been invisibilized, and because of that, our communities are experiencing so much hate during the pandemic and long before. And so what I think is crucial is that our city finally sees our communities, makes sure that we are getting services, resources and government in our languages, and that the City takes seriously the immense prejudice and hate our communities are facing and works to end them.

As an Indian American, what does your identity mean to you, and how has it influenced your work as a City councilmember?

I think representation is such an important piece of government — making sure that our communities and our voices are heard, making sure that the youth of our communities see themselves represented in government, too.

That’s the perspective that I bring both as an Indian American and a civil rights lawyer. That’s why I’m so passionate about fighting to make sure that the voices of our Asian American communities are heard, whether it’s fighting for the taxi workers of our city, many of who are South Asians, whether it’s fighting against Asian hate and bigotry, or whether it’s fighting for language access. These are all issues that, as an Indian American, I’ve seen personally, and I know how urgent the issues are.

May is AAPI Heritage Month. How do you plan to celebrate this month, and what do you hope people will learn or take away from this celebration?

My office is planning a variety of different events to participate in, to host, and to celebrate the AAPI community and discuss the issues that are really important to us that need to be heard.

A big part of the issues we face is that many people don’t know the history, heritage and needs of our communities. And that is very much true when it comes to government, as it is true for our educational material where our students don’t see themselves in the materials they are learning. I hope when we come out of AAPI month, we see a renewed focus by our city. I’m really making sure that the urgent needs of our AAPI communities are addressed.

Do you still keep any traditions from your culture? Are there any festivals or celebrations that you and your family celebrate every year, and what do they mean to you?

That’s what we just did. I’m very close with my family and my parents. We celebrate the traditions and pass them down to our children, too. We just actually celebrated the Vishu, which is the South Indian New Year in Kerala. We all got together as a family, and I celebrated the day this past Sunday [April 16]. It’s a time where there are a lot of different New Year events in Asian American communities, whether it’s Songkran for our Thai community or Vaisakhi for our Sikh community.

I think all of these traditions are one way to really both share as a family and pass on from generation to generation to keep our traditions alive, and they also function as a way to make sure that our city and society overall do not invisibilize us, but actually see us for our tradition and recognize them.

That’s why I would also say, in part, that’s why our fight to make Diwali a school holiday in New York City is so important. That’s why it is so important to have to fight to make Lunar New Year a school holiday, and now we do have Eid as a school holiday. All of these things are ways that we can spend time with our family. But also, it’s a way for governments to really recognize and respect our cultures and traditions.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.