In 1903, Nicholas Capiello, a building contractor, received a letter with daggers drawn on it. The message was clear: if he didn’t pay $10,000 in cash, his home at 107 Second Place in Brooklyn would be dynamited. The gangsters signed the letter with “Mano Nera,” or “Black Hand,” when translated from Italian.

Although the Brooklyn police quickly solved the case and two men were jailed, individuals saw that sending threatening letters claiming to be from the “Black Hand” could induce fear. Consequently, extortionists started employing this strategy to pry money from people.

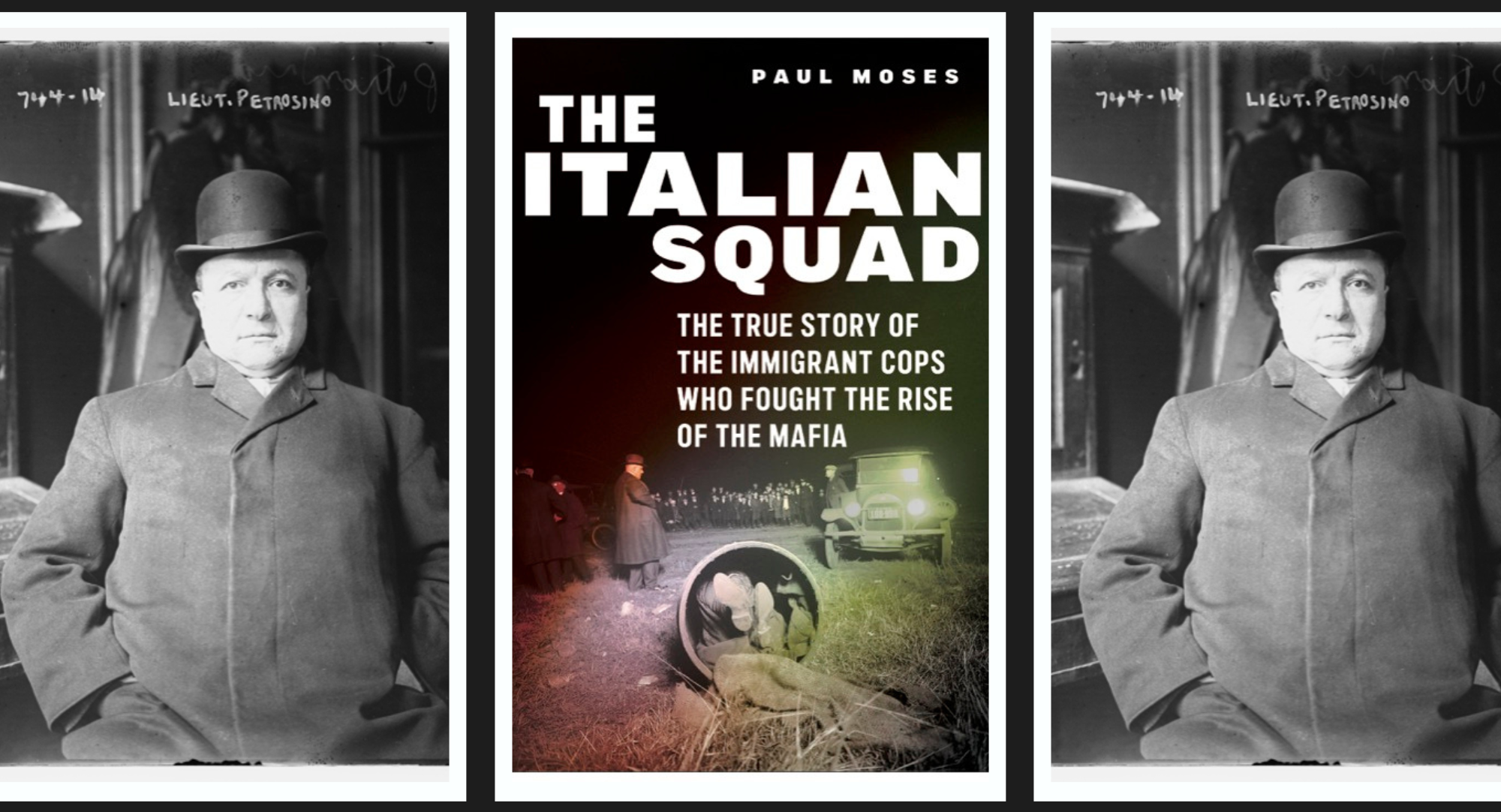

The concept of the “Black Hand” — which was already popular in Europe prior to it gaining attention in the U.S. — captured the interest of the media. Paul Moses’ writes in his new book, The Italian Squad: The True Story of the Immigrant Cops Who Fought the Rise of the Mafia, that “often inaccurate coverage of the so-called Black Hand, which the [news] papers thoroughly confused with the Sicilian Mafia and the Neapolitan Camorra” all led to “the notion that Italians were inherently criminal and therefore unfit to be American citizens.”

Extensive media coverage of a few crimes committed by Italians contributed to the tendency of the general public to perceive all Italian immigrants as a monolith or homogeneous group, unfairly associating them with criminal behavior. The depiction “furthered the false narrative that the “Society” of the Black Hand was a single enormous conspiracy, masterminded by the Sicilian Mafia and Neapolitan Camorra,” Moses writes.

The news coverage of the Black Hand fueled harmful arrests and laws that affected the wider growing community of Italian immigrants. That coverage resembled how the modern media would later discuss crimes committed by undocumented immigrants. Still, the Italian community and the press demanded action due to the increasing crimes associated with the Black Hand.

The New York Police Department formed a special unit called the Italian Squad in 1904 as a response to public outcry against the Black Hand.

The Italian Squad of the NYPD consisted of two dozen Italian-born police officers, led by renowned detective Joseph Petrosino. In 1909, Petrosino was sent to Italy to gather evidence for deporting suspected criminals in the U.S. with prior records in their home country. Tragically, he was murdered while there. The book explores the officers’ role as intermediaries between the Italian community and the police, highlighting historical prejudices faced by Italians and makes a case for readers to be able to draw parallels to the current targeting of immigrants, and minority groups as criminals.

The Italian Squad is Paul Moses’ fourth book, which is set to launch on June 13 at Casa Belvedere, an Italian cultural institute on Grymes Hill in Staten Island — explores the complex dynamics between the police and the Italian community, prompting readers to reflect on the past to encourage a more thoughtful discussion about the present.

Moses is a Professor Emeritus of Journalism at CUNY-Brooklyn College and a former reporter and editor, who has also written and edited for Documented. He is the author of An Unlikely Union: The Love-Hate Story of New York’s Irish and Italians and The Saint and the Sultan: The Crusades, Islam and Francis of Assisi’s Mission of Peace.

Fisayo Okare: The Italian Squad included two dozen Italian-American police officers. How did the New York Police Department pick these officers to join the special unit? How was it formed?

Paul Moses: They had a problem; they had very few Italian officers or Italian-speaking officers. So who would become a detective on the squad would just be some of the more effective Italian-born officers. But I noticed that a lot of these officers had problems getting hired, and advancing. It’s hard to look at any individual case, and say it’s a matter of discrimination. But when you see it happening over and again to police officers who later became nationally famous for their work, you could sense that Italians were a minority group at that time, and were treated as such. But yeah, they had to take a test, same as anybody else who is in the civil service system.

What led you to write the book?

I came upon it when I was writing about the history of the Irish and the Italians and the police department in New York — as you probably know, is historically dominated by the Irish. As I was writing about the Irish and the Italians, I thought it’d be interesting to write about Joseph Petrosino — the famous officer — and what it was like for him to advance in an Irish-run department. It’s just a good story. It seemed like something that could really sustain a book of its own. So there’s a chapter on it in my earlier book, but I wanted to explore it further, especially with immigration being such a big issue. City politics enters into the story quite a bit too.

While officers in the Italian Squad did the detective work they were appointed to do, do you think they managed to fight prejudice against their own community in so doing?

They themselves were very much treated as heroes at the time. So it did show that an Italian could be a responsible American. One thing to keep in mind, and I think it’s a difference between our own day and that day, is that there were eugenics theories, really, totally racist theories, saying that certain races, nationalities were inferior or superior. Southern Italians were kind of way down by the bottom of that. They were convinced by the shape of their skulls and all kinds of crazy things at that time. This is not just an opinion held by uneducated people, but experts, professors, and people would write on this stuff seriously. I think it influenced the reporters and the judges and so Italians were really seen as unfit to be American citizens.

So just to have Italian immigrants who succeed, and Petrosino, when he was murdered, he was just treated like a martyr by the whole populace, not just Italians. I think in that sense, they helped the Italian cause. The problem was that they made a lot of good cases. But every time they made a case, it just showed in the newspapers that ‘oh all these Italians are criminals,’ they keep arresting them. It was a slippery slope for them.

How did you end up deducting from what you’ve written? What did it mean to you, after telling all of the stories in the previous chapters?

Some of it is about policing, what works, and what doesn’t work. I think the story of the Italian squad shows the importance of having good relations between police and the community. The Italian Squad was really a bridge between a community that really distrusted police intensely, and between the police who didn’t like the Italian community very much. I also saw that a lot of stricter approaches to law enforcement were pioneered on Italians: racketeering laws, even gun control law in New York State, Sullivan law, holding people without bail, etc.

One thing I learned was kind of: your weakest link in civil liberties affects everybody eventually. All of these laws applied to everybody but were passed because the public was so outraged about a crime by Italians. There was a serious crime problem but it was really exaggerated and focused on, to the exclusion maybe of other groups. All of these things, I sorted out and then tried to understand what their legacy was in law enforcement.

The book references a coverage of the New York Times, which reads “We have too many bad Italians already,” and it acknowledged that some good individuals may be deported with those who commit crime “that will make no difference,” the report noted. “Protect ourselves, we must.” This suggests that even mainstream media displayed bias against immigrants at that time. What influence do you think such coverage had in convincing the general public that immigrants are a burden to society, and predominantly caused the crime happening at the time?

I think the media coverage contributed a lot to anti-immigrant sentiment, which eventually peaked with the passage of a law in 1924 that sharply limited the number of immigrants who could come to this country from Southern Europe and in Eastern Europe. Those are the two largest waves of migration. There were other laws separately that excluded Chinese. The exaggeration of Italian crime contributed a lot, and the news media played a big role in that.

When people pick up this book to read, what are three major takeaways that you would want them to take from the book?

First, I would like people to just enjoy the story and the characters. As a writer, there’s just nothing like telling a story when you have a story to tell. On policing, I’d like people to think about the importance of police and community relations. On immigration, I mean, my takeaway is that these Italians were considered to be so despicable at that time, but they certainly became a group that made major contributions to the life of the city. I think that the same is happening with other immigrant groups who come now, so maybe in a kind of a gentle way, I am trying to say that to readers. I’m sure you’ve noticed from your own writing, you never can control what people are going to take away from what you write. But I hope people see that and reflect on immigration in their own time period.