Over 70,000 asylum seekers have arrived in New York City since last spring, many of whom rely on city agencies and public resources to access shelter, food, and other necessities. The recent migration has also been reflected in the number of new members who have signed up and contacted Documented via our WhatsApp platform, boasting more than 5,700 members.

One third of the members in our WhatsApp community identify themselves as asylum seekers who have entered the country in the past year. They have sent us comments that led to nuanced stories about the lack of lawyers available to file asylum cases before the one year deadline, and also resources to help migrants update their address with immigration agencies.

Last year, based on the questions that Documented received, we revisited the resource guides we created for immigrants during the pandemic and launched two new websites in October (www.nuevosinmigrantes.nyc and www.newimmigrants.nyc) to answer the questions newly arrived migrants had. Our goal is to use the feedback we received from asylum seekers in our WhatsApp channel, and then see what resources were the most useful to get them started with finding shelter, food, legal assistance and more.

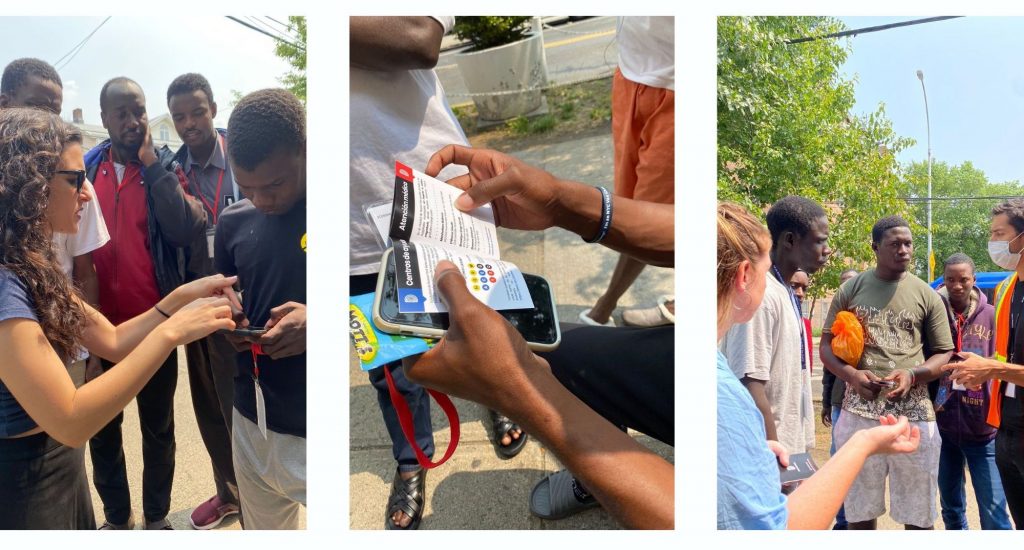

We then set out into the streets to deliver flyers with QR codes at shelter locations where we met migrants who had been unaware that certain resources were available. As Documented reported, many have stated that shelters often lack information about what resources migrants can access.

The QR codes became the second traffic driver to our website and immigrants that found our journalism helpful shared it with people back home. We can track that people scanned the QR code from as far as Colombia.

Although the websites were successful, throughout the year we encountered a different problem: lack of internet access.

Going back to the WhatsApp community, along with the reporting that the team had done at Documented in the past year, we decided to — once again — narrow down the resources we had created to ensure that migrants with low digital literacy could access useful information on the services available in New York City.

What resulted was a 10 page pocket-sized booklet in Spanish that listed addresses, contacts and directions to centers where they could obtain assistance as soon as they landed in the city. It also included a guide on how to access free internet services and the contacts for support during a mental health crisis. We want them to carry the booklet with them as the information is evergreen and can be handy whenever a new issue arises.

Distribution at respite centers

Journalists Lucía Cholakian Herrera and Rosario Marina — both of whom joined Documented for a month last year through ICFJ’s emerging media leader’s program — returned in 2023 to distribute the booklets in respite centers.

Their first visit was the Roosevelt Hotel in Manhattan. They introduced themselves as journalists to the security guards at the location, who were skeptical of their presence there and did not want them to interact with the migrants in the premises. At one point, one of the guards kept checking in on them from the corner.

But many of the migrants there — from Venezuela and Colombia — approached Marina and Cholakian Herrera. They told them that they had been bussed from Texas to NYC after being released by immigration authorities. For some, it was the first stop before reaching their destinations, like Washington DC or Ohio. For others, New York was the end of a long journey. An 18-year-old had been detained for a month in the southern border with his father. He said he managed to demonstrate credible fear, but his father had not, and was still detained as of mid June.

The look of desperation and anguish was visible on their faces. They had walked through the Darién Gap jungle for almost a month only to enter the complex immigration system is in the states. Many did not understand how to move forward with their asylum cases, and some of them asked if it was possible to return to their countries.

When we shared the booklets we had created, some began asking questions while others stayed quietly in the back. But they all seemed to be browsing the booklets very carefully.

Some said they were being offered buses to cities in the north, bordering Canada, and that they didn’t want to go. Another migrant said that he had gone to the Roosevelt Hotel to complain because there were many problems in the shelter but that the people at the front desk told him to be thankful that he had a place to sleep.

We also saw how they were taking migrants in public buses, with signs that said Not in Service. The migrants said they often did not know where they were being taken to.

At a respite center in Astoria, Queens, the majority of the population was from African countries — Senegal, Congo and Mauritania. As Marina and Cholakian Herrera spoke only Spanish and English, communicating with the migrants was a difficult task. Cholakian Herrera used Google Translate on her phone to ask questions, and then passed the phone to the migrant so that they could speak into it for the translation to appear on the phone.

The migrants were desperate to know what was in the booklets. They were desperate for information. Only one staff member at the respite center spoke French, but they could not understand each other fully.

It was very difficult to see migrants unable to access information in a language they could understand. It showed that there is still a need for language access.

Aside from the language barrier, there was a need for understanding how to access IDNYC, the differences between affirmative and defensive asylum, along with who is eligible to get a work permit and when they can apply for it. Although the information exists they do not have access to it.

Some who spoke with Documented expressed intentions of going back to their countries because of how lost they feel. They said they maintain hope by trusting in the plan that God has for them.

The next steps

After seeing success with the first batch, we are adjusting some of the content based on what was observed during the distribution of the booklets. Organizations and individuals working with asylum seekers have reached out asking for the guides. If you work with asylum seekers and would like to receive some physical copies, send us an email and we will reach out to you.

Also Read: Asylum Seekers Use WhatsApp to Navigate NYC With Documented Journalists