Earlier this year, after Mexico’s CONCACAF Gold Cup win in July, a short clip went viral. ESPN reporter José del Valle approached a child in Inglewood, California, on live TV and said to him in Spanish, “Cuál es tu nombre?”

“My name?” The child said. The reporter responded with other questions in rapid succession, as the child looked to an adult off-screen for assistance. Then, the child looked back at the reporter and said “What?”

The anchors of the “Fútbol Picante,” on the receiving end quickly filled the airtime with a comment in Spanish: “Does not understand. It is a generation that no longer speaks Spanish.”

The clip now has 1.5 million views on Twitter with the caption “Raise your kids not to be ‘yo no sabo,’” which is an incorrect way of saying “I don’t know.” It’s a phrase used to describe kids who may not be fluent in Spanish — and it’s often to shame the child, my colleague, Giulia McDonnell Nieto del Rio, tells me.

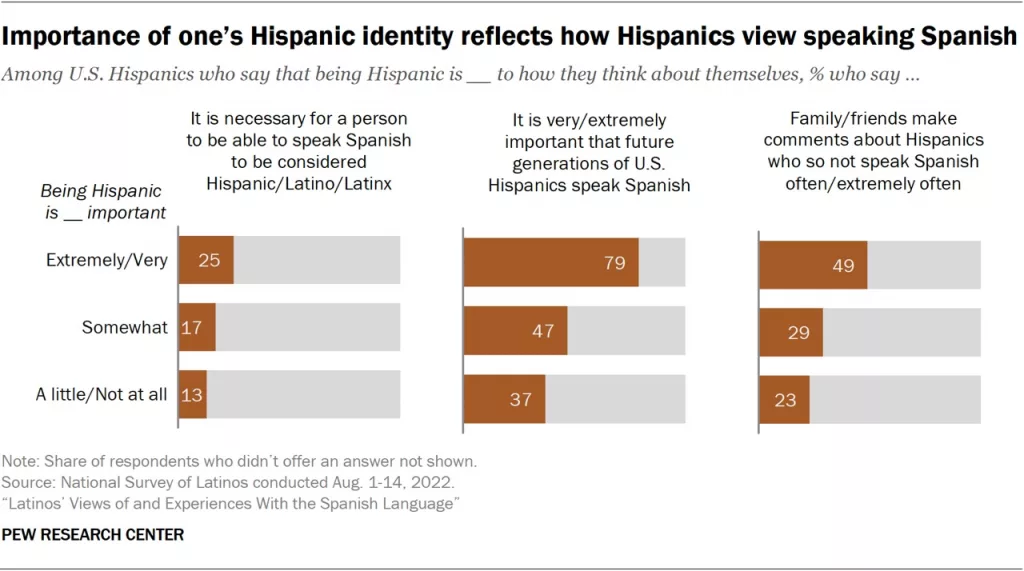

The clip is referenced in Pew Research’s latest study about Latinos’ views of and experiences with Spanish language in the U.S. The report shows that speaking Spanish is a core identity for U.S. Latinos, and those who don’t have been shamed by their community for it.

Over half (54%) of U.S. Latinos who admit to having limited or no ability to converse in Spanish have experienced instances where other Latinos made them feel bad for their limited capacity to speak the language, the report states.

“I think Spanish is a beautiful language and I love that it’s the language of my culture,” Rachel Fernandez, 31, who was born and raised in the U.S. and lives in Seattle, tells me. “But there is a deep shame about it I hate because of the bad experiences I’ve had with people judging me because I don’t speak it.”

Fernandez’ household uses more of a Spanglish (a mix of English and Spanish) dialogue in their everyday speech. As a result, she often says some words in Spanish because she was raised using that Spanish word in place of an English word. But when Fernandez throws in a Spanish word when talking in English to a Spanish speaker, they often think she can speak Spanish and switch over, she explained.

It’s “very embarrassing … and I have to explain myself like I’ve done something wrong,” Fernandez explains. “My relationship with Spanish is more negative than positive. I feel like I have to love it in secret and that I can’t show my pride for my culture because of it.”

Fernandez, who works in customer service, spoke about the sense of guilt that a customer at her workplace had evoked in her.

“I had a customer, Julio, come into my job who spoke English. But because I’m Mexican and I look it, he asked me if I spoke Spanish, when I told him that I didn’t, he responded by telling me I was a fake Mexican, [and] a mixture of shame and rage made my eyes become tearful,” she says. “But the shame does not end with Julio.”

Mark Hugo Lopez is Pew Research’s director of race and ethnicity research, and he co-wrote the latest report. He told Documented that the survey’s question about the shame surrounding not speaking Spanish was “one that we’ve never asked before. So we wanted to put some numbers to the phenomenon.”

The majority of Latino adults (78%) say that you don’t have to speak Spanish to be considered Latino, while 21% believe it is necessary. However, the study found that U.S.-born Latinos are more likely than Latino immigrants to say speaking Spanish is not necessary to be considered Latino (87% vs. 70%).

Latino identity in the U.S. can be influenced by various elements, with one being the ability to speak Spanish, which some Latinos use as a distinguishing factor between who is Latino and who is not, the report states.

“I don’t think there’s only one way to be Hispanic [or Latino],” Mónica Espitia, the founder and executive producer of Pulso y Péndulo, a weekly news podcast in Spanish, tells me. “The way people choose to express their cultural identity is very personal and depends on their lived experiences,” she said.

Spanish is Espitia’s first language because she grew up in Latin America. It is the language she uses to communicate with her family.

“It’s also how I connect with my younger self. I lived in Colombia until I was 17, so all my childhood memories are in Spanish,” she explained. “But that’s not the case for everyone and that doesn’t make them any less Hispanic.”

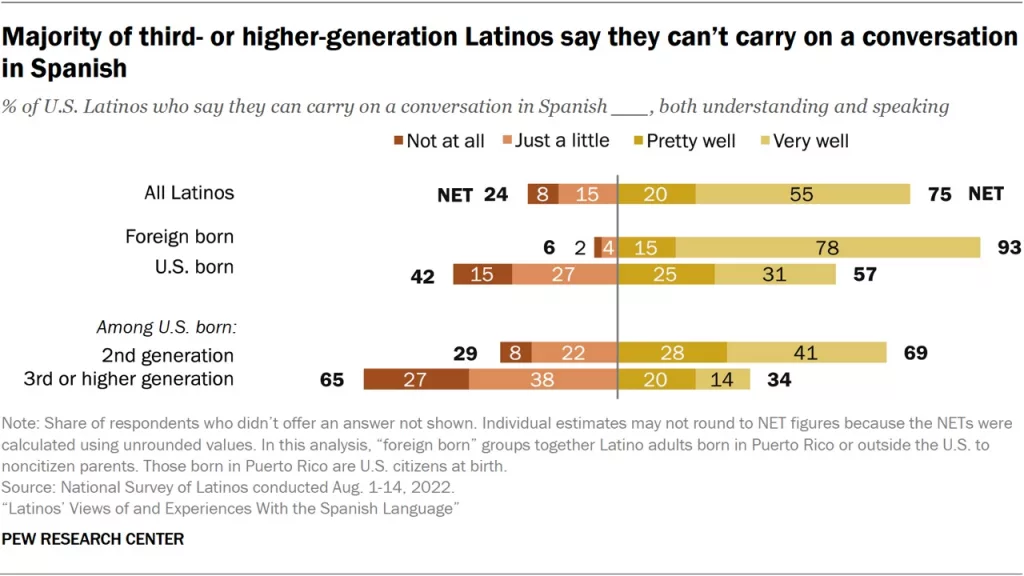

While almost all Latinos born outside the U.S. report proficiency in speaking Spanish, the proficiency in Spanish language diminishes across successive immigrant generations, as the chart below shows.

“Learning a language, especially when you’re not constantly exposed to it, is very challenging,” Espitia explained.

The U.S. is one of the world’s largest Spanish-speaking countries. After the English language, Spanish is the most commonly spoken language in the U.S., with close to 40 million Latinos speaking Spanish at home.

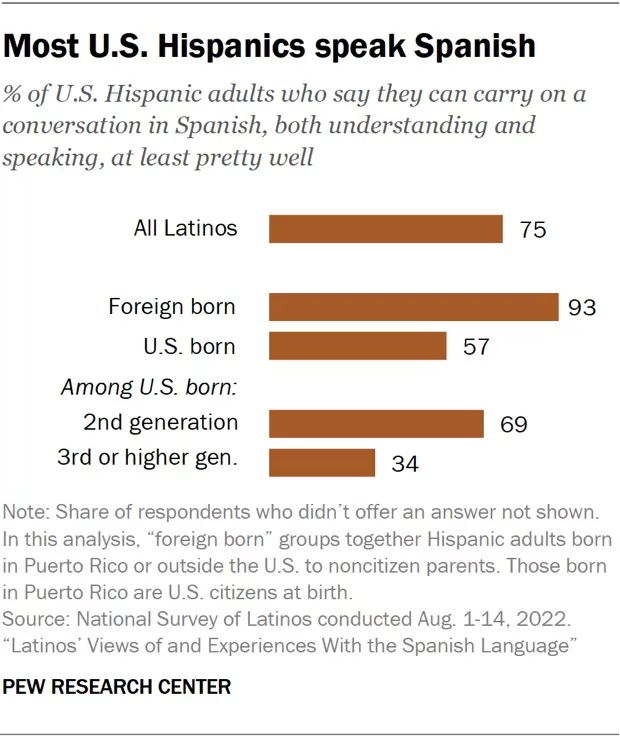

Most Latinos (both immigrants and others) report being able to carry on a conversation in Spanish pretty well or very well, accounting for 75% of respondents. A much smaller majority (57%) of all U.S.-born Latinos report the same, Pew Research found. The percentage begins to decrease across other generations.

The report’s findings show an interesting contrast among Latinos in regards to speaking Spanish. On one hand, 85% of all Latinos (both immigrants and across other generations) say it is important that future generations of Latinos in the U.S. speak Spanish. On the other hand, 78% say you don’t have to speak Spanish to be considered Latino in the U.S.

The report’s findings reflect the aspirations of Latinos, given many Latino parents want their children to speak Spanish, Lopez explained they’ve found that in previous surveys too.

Findings from the study also show other insights in regards to political party affiliation. Close to nine-in-ten Democratic and Democratic-leaning Hispanics (88%) say it is at least somewhat important for future generations of Hispanics in the U.S. to speak Spanish, with 36% saying it is extremely important. Whereas, 80% of Republican and Republican-leaning Hispanics say it is at least somewhat important for future generations of U.S. Hispanics to speak Spanish, with 26% saying it’s extremely important. The gap in the responses of both groups albeit are not too wide, showing that the majority generally say it is important.