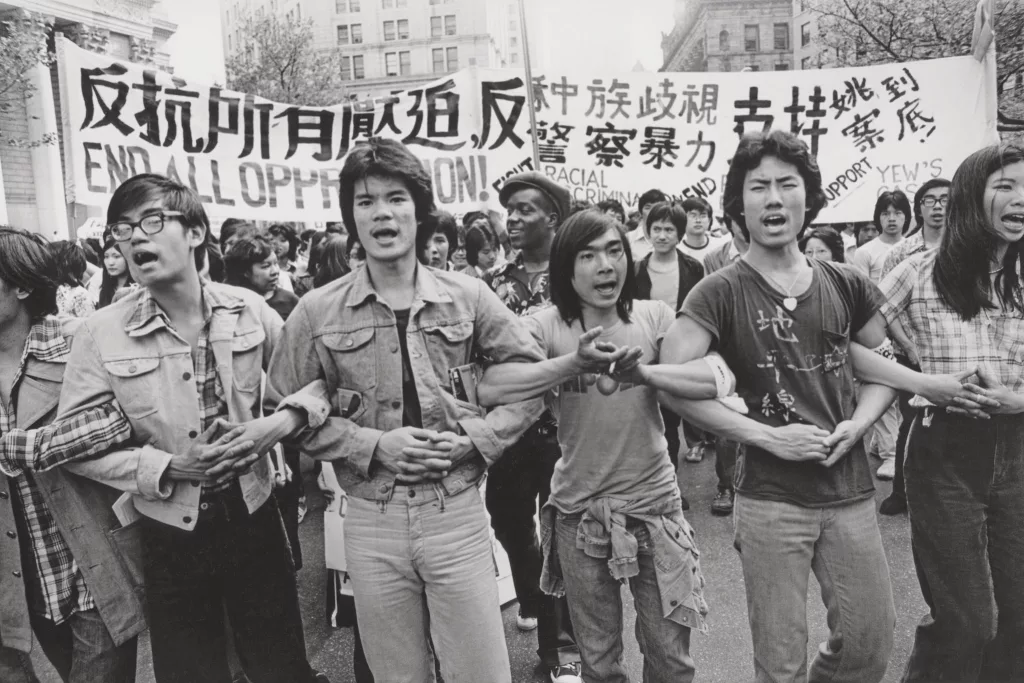

As an observer and as a photojournalist, Corky Lee appeared at numerous pivotal moments within the Asian American community in New York and beyond over the past half-century. In photos, he documented the unnoticed facets of the rapidly growing community in the U.S., portraying everything from everyday life to social justice movements. In doing so, he broke the stereotype of Asian Americans as docile, passive, and foreign to the country.

Also Read: Corky Lee Remains on Chinatown’s Mind

Lee’s extensive body of work has gained widespread recognition and had a profound impact. Some of his pieces have been featured in publications including The New York Times, Time Magazine, Associated Press, The Village Voice, among others. In 1988, former New York City Mayor David Dinkins designated May 5 to honor Lee’s body of work. A second tribute occurred on May 7, 1993, when “Corky Lee Day” was announced to commemorate his outstanding work on behalf of the Asian American community.

Tomorrow marks the third anniversary of Lee’s death. He died at age 73 from complications due to COVID on January 27, 2021. The death of this beloved and legendary photographer has garnered significant attention from major Chinese-language media and English-language media outlets in the U.S.

On April 9th, the first book of its kind, “Corky Lee’s Asian America,” will be published nationwide online and in bookstores. Visual artist Chee Wang Ng and Columbia University history professor Mae Ngai have curated a retrospective of Lee’s work. The project began after Ngai was approached by John Lee, Corky’s brother, who was asked by a publisher to pull together a book of his work. This collection includes never-before-seen photographs alongside his best-known images, spanning from his early days in New York’s Chinatown in the 1970s to his coverage of diverse Asian American communities across the country until his untimely passing in 2021.

Documented interviewed Ngai about her reflections on editing the book and her personal connections with Lee. Ngai told me that during the peak of the pandemic in the last few months of Lee’s life, he dedicated himself to capturing a series of photos that featured Chinese Americans in front of their favorite Chinese restaurants in Chinatown. The series aims to encourage the public to visit and support the Chinese community facing challenges from both COVID-19 and anti-Asian hate. Surprisingly, I discovered that I was a subject in this series, a fact I had forgotten amidst intense reporting and daily trivial matters during the pandemic.

Perhaps, like me, many others have been captured as a microcosm of the Asian community through his lens. Reading this book, you may find yourself or someone like you.

The article is written in a Q&A format. Due to length constraints, some answers have been edited.

April Xu: Could you explain the process of selecting the images featured in the book? What criteria did you use, and why do you consider these pictures important?

Mae Ngai: We wanted this to be Corky’s book. It’s his photographs, it’s his book. We started with photographs that he himself selected. In 2011, when he was interested in self-publishing a book of his photographs. But that never got completed, you know, how things are, things get in the way, and you’re busy. But he selected 100 photographs. So we started with that, because that’s what he envisioned for his own book.

That 100 was also mostly Chinatown and Chinese Americans. So we wanted to be broader. We added photos that he took after 2011. For the next 10 years, we selected another group of photos, that also he himself had exhibited in shows or contributed to documentaries that people were making. These were his selections, what he considered to be his best work.

We also kept in mind the need to have a broader range than what he had done for the first book project. Those two selections from his first 40 years and then those he considered to be his best work from his last 10 years, so that’s the core of the book. And then we added some other things. First, Corky did not like to exhibit photos of personalities, famous people, like elected officials, or Hollywood types. He very strongly believed that it was the ordinary people and the activists that should be highlighted. But we added some of those pictures into the book because they are part of the historical record of Asian American arts and culture and politics. And he took them for that reason. And then we also found some photographs in his files that nobody’s seen before. So we added some of those. I think the main body of the photos are photos that he considered to be his good work, and then we added to that.

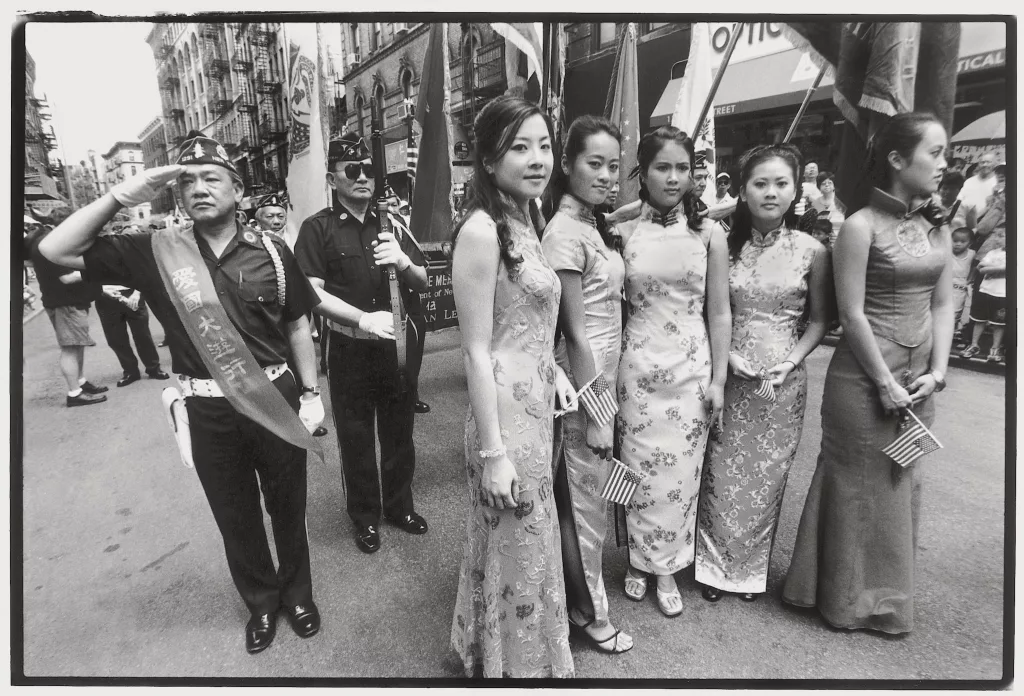

I think that he chose those pictures based on having both photos that showed typical, everyday life in the community and that showed the civil rights struggle and movements for social justice. Those are the two general criteria he liked to have. Corky liked to take photos that had a kind of irony. He liked to show contrast. For example, he had a photograph of the Fourth of July parade in Chinatown in 2005, he had these women who were contestants in a Chinatown beauty pageant and then next to them were contingents of Chinese Americans or veterans from the American Legion, so that’s a kind of contrast. He liked to show different aspects of the community.

Can you give me a few examples of the photos you particularly like in the book?

There are so many. He has his famous series of photos taken after 9/11. The most famous one is the one of the Sikh man draping himself with the American flag that was very famous. I also like the photos he took to show a lot of joy and pride in the community. Like he has a picture of a dragon boat club after they won a 500-meter race in Flushing in 1995. That’s just a great photo of people being very happy and exuberant.

In fact, I would say, a very large number of Cork’s photographs are composed, and not spontaneous. Because he himself is trying to tell the story. So sometimes they are action, photos, pictures, he has photographs of people marching in protest, that kind of thing. But even those are very carefully composed.

He loved to show Asian Americans in ethnic parades wearing their ethnic costumes, but holding American flags. He likes to do that in order to show that you can be an Asian American and be proud of your character.

Did you have any personal connections with Corky Lee? If so, could you share a memorable story or experience you had with him?

I have known Corky from the early 1970s. We were both activists in Chinatown. So I knew him all the way back in the early 70s. He’s always at every event. I would always see him. More recently, because I’m a professor at Columbia and when I was the director of the ethnic studies program at Columbia, I invited Corky to show his photographs at our gallery in 2019. I invited him up. We had lunch, we talked about stuff. And then I told him, I wanted to see if he could mount a show. I said, well, what kind of theme do you want? It was interesting because he has such a broad range of photos and so many different topics. And he says, well, I guess I have to think about it. We never really got that far, because that was in 2019. And then just a few months later, everything shut down. The COVID. He never made the show.

What were the last months like for Corky during the pandemic, did he still try to take some photos?

He always wore masks. His photos were mostly in Chinatown. He didn’t travel to other cities or anything because he couldn’t. But he went to Chinatown here. He showed a lot of photos of Chinatown being deserted, stores being shuttered. He showed in the winter, a woman bundled up in winter clothes selling masks and sanitizer on Canal Street. So he also wanted to show that Chinatown and Chinese people were victims of the virus, not the cause of the virus. And he wanted to show how people were coping with the pandemic damage to the local economy. He did a lovely series where he invited people to stand in front of their favorite Chinese restaurant. He wanted to show the same thing after 9/11 that Chinese Americans and Chinese people were not the cause of these problems. But they were hurt by that as well. That was his intention.

As you worked on editing this book, what reflections emerged for you? Additionally, what key messages do you aim to convey to the audience through the content of this book?

I would say two things. First, I think the way we organized the book was chronologically by decades. A lot of people know Corky’s photographs because they’re on the internet, and they’re kind of random. When you put it all together the way we did by decade and with different themes, you can see a kind of arc of Asian American history that you would not otherwise see. So we put it all together as a historical narrative of our communities in this era after 1965 when we had new immigrants. And it’s a narrative of our movements for social justice.

The second thing is that I really feel that I was the editor, but the author is Corky. It’s his photographs. I think it’s very important that we selected photographs that he himself had selected for a book or for other exhibits. We wanted to reflect Corky’s own values and what he thought about his own work. So we did a lot of work to organize it and to tell the story. I wrote introductions to each chapter to put it in context. But I feel very strongly that it’s not my book.

Where and when will the book be available for purchase by the public?

The books will be sold online or in any bookstore nationwide starting from April 9th.

Note: Reprinted with permission from Corky Lee’s Asian America: Fifty Years of Photographic Justice.

Copyright © 2024 by the Estate of Corky Lee, Mae Ngai, and Chee Wang Ng. Text copyright © 2024 by Mae Ngai unless otherwise noted. Photographs copyright © 2024 by the Estate of Corky Lee unless otherwise noted. Published by Clarkson Potter, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.