Day after day, dozens — sometimes hundreds — of young migrants gather at a drop-in center for youth on a busy stretch of 125th St. in Harlem. Young men congregate in the main room with their lunches from the kitchen, resting on couches and chairs and watching sports on their phones. The sound of laughter and chatter in Wolof, French and Arabic, among other languages, permeated throughout the space last Thursday, and bright red Valentine’s Day decorations remained from the day before. The center has become a respite for these young migrants, providing them with warm meals, showers, lockers, and peer groups for the youth to connect with each other.

Many of these young men recently arrived in New York from Mauritania, Senegal, and other West African countries. Most have been housed with older migrants in congregate settings, where every 30 days they must begin their search for a new cot, even though New York has specific facilities designated for homeless youth.

Some advocates say they have even encountered unaccompanied minors, who they say have been slipping through the cracks and are unable to access programs built to assist them.

The Coalition for Homeless Youth has received calls about numerous 15-, 16-, and 17-year-olds, as well as one 14-year-old. According to Advocacy Coordinator Lauren Galloway, they were coming to the city “by themselves.”

Also Read: What the 60-Day Eviction Rule Means for Migrants in NYC Shelters

Since about October 2023, Galloway has noticed an uptick in the number of migrant unaccompanied youth under the age of 16 arriving in the city who appear to be without a guardian. “It’s unlike anything we’ve ever seen,” she said.

Unaccompanied migrant minors — children in the U.S. under the age of 18 without a parent or legal guardian — are entitled to specific protections under federal law and are transferred to the care of the Office of Refugee Resettlement in the Department of Health and Human Services after they are apprehended by the Department of Homeland Security. They are often released to sponsors. Once migrants turn 18, they leave HHS custody — though sometimes they are transferred to Immigration and Customs Enforcement custody — but may still be eligible for specialized shelter in New York until they turn 25. Many migrant youth would meet the requirements for spots in city shelters for youth between the ages of 16 and 24. But New York has run out of space there, too, advocates say.

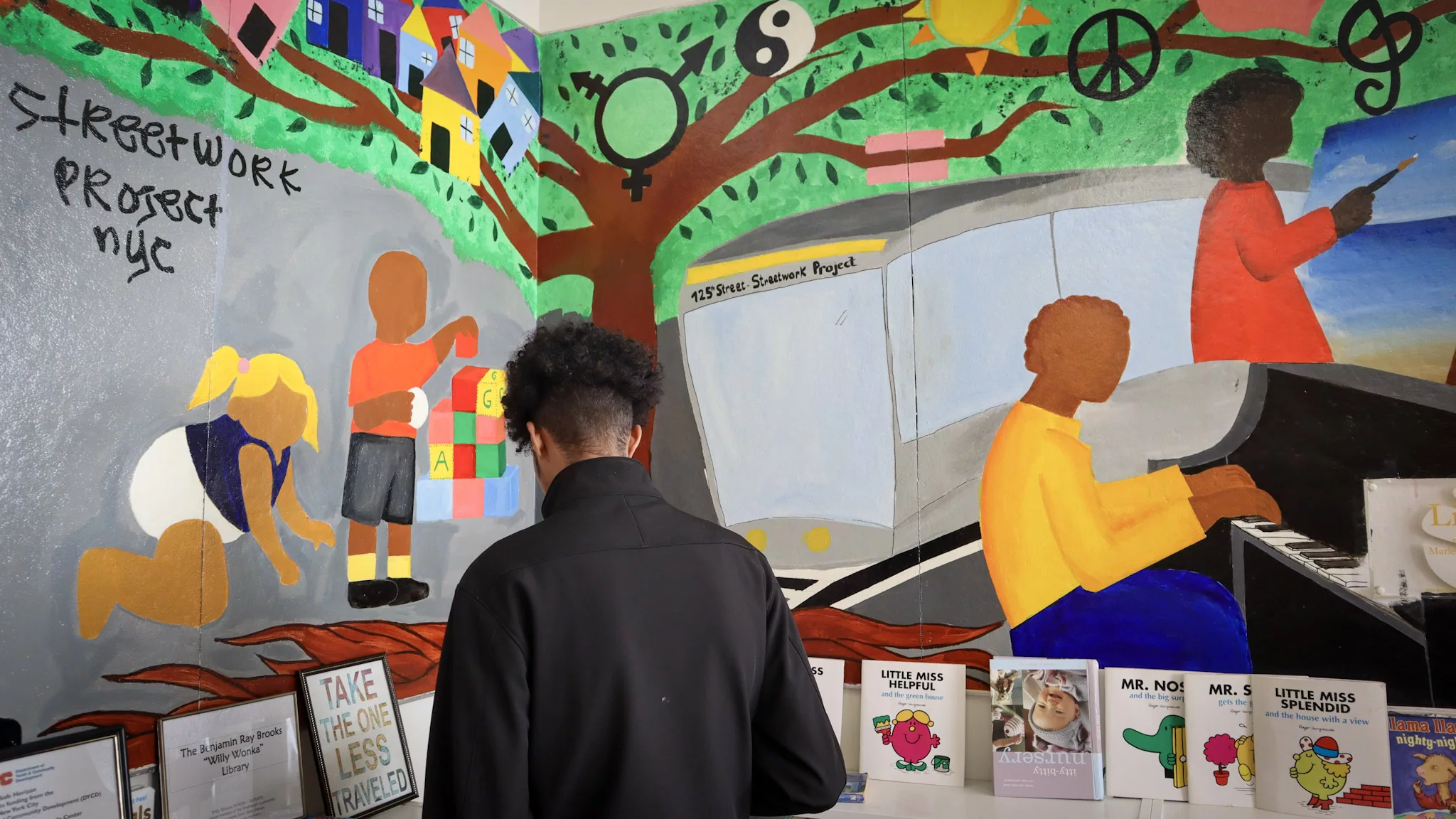

“There’s just not enough beds, and there’s just not enough resources,” said Sebastien Vante, the associate vice president of Safe Horizon’s Streetwork Project in Harlem, the center that offers drop-in services during the day for youth experiencing homelessness.

“For a young person who is looking to connect with school and looking to find employment, if they’re being discharged from 30 day placements every 30 days,” Vante said. “It’s like, where do they find that kind of stability if you don’t know where you’ll be in a month?”

Before young migrants started coming to the center, Streetwork would see about 60 youth a day, Vante said. But now, anywhere from 160 to more than 200 people, many of them young migrants asking for shelter, come to the center every day.

“The sheer volume of young folks coming into our space is something that we haven’t experienced before,” Vante said. “Staff are a bit overwhelmed because it is a lot to manage, especially considering that the resources for this particular group are very limited.”

Sidi Mahmoud, a 20-year-old from Mauritania, comes to Safe Horizon’s Streetwork Harlem drop-in center almost every day. To get to New York, Mahmoud flew from Mauritania to Turkey, then took another flight to Colombia. Afterward, he headed north on boats, buses, and by foot. Mahmoud has been in New York for about six months and was placed in a congregate shelter in Brooklyn for approximately two months. He didn’t know that he could be eligible for any other housing options besides sleeping with at least a hundred other people in one room. And then, the city imposed shelter stay limits, so he had to leave the facility last year.

“I found myself in the street,” Mahmoud said during an interview this week at Streetwork in Harlem. Initially, he slept for a few nights in a mosque and left the state for some time without knowing where to go. Then he came back, and a friend referred him to Streetwork in Harlem. Here, his housing situation has become more stable.

The program helped find him a crisis shelter that offers immediate space in a facility for youths, from 60 to 90-day stays (pending space in the system). He then transitioned into a transitional independent living facility where he can stay for up to two years. “I got enough time to get everything set up, and now everything is good,” he said.

Mahmoud said that he has created a community at Streetwork in the four months he has been going to the center and called staff at the facility “very helpful.” Among other services, the Harlem center offers a space during the day where youth can take showers, sleep, and eat hot meals — basic needs that migrants say are rarely addressed at the city’s “overnight hospitality centers,” where migrants are directed in the evenings when waiting to be reassigned to shelters.

“I spent almost two months in New York and I was almost lost — I didn’t know where to go,” he said. “But the moment I came [to Streetwork], I found myself with people who are very kind.”

Mahmoud now refers to other young migrants that he encounters to Streetwork, and has found a lawyer to help him obtain his work permit, he said. Having housing security, Mahmoud said, was crucial to being able to attend school regularly. He’s taking classes to receive his G.E.D., where his favorite subject is social studies. One day, he hopes to run his own company.

Mayor Eric Adams said on Monday that the city has cared for more than 177,000 migrants since last spring and that over 80% of single adults in the system have left city facilities. “I drive around the city all the time and see, do we have encampments? Do we have people sleeping in large tent settings? No,” Adams said. “We responded to the crisis, and we are going to continue to do so in a humanitarian way.”

At Streetwork, the center is specifically equipped to assist youth experiencing homelessness, and has had to expand its resources in order to meet the needs of migrant youth since a large number of migrant youth began showing up early last fall, said Vante. Streetwork is looking for volunteers, especially French speakers, to come on site to translate. The center has had to adjust the amount of food they cook, help address their legal needs, assist them in connecting to schools, and is looking to hire bilingual therapists. Streetwork has also been responding to cultural needs and wants by, for example, setting up prayer rugs, cooking West African food, or putting the Africa Cup of Nations soccer matches on television.

Streetwork is a Runaway and Homeless Youth program funded by the city’s Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD). The center can refer youth who come to them only to a “finite” number of beds that are available for their criteria, Vante said. DYCD has just over 750 shelter beds across the city. The conditions in the youth shelters allow more space and privacy than the congregate setting of a Humanitarian Emergency Response and Relief Center (HERRC), both Mahmoud and Vante said. “It’s very different from being in a HERRC,” Vante said, “where there’s 100 people head to toe inches apart from each other.”

Mahmoud was able to access a bed after months in the adult system. But that is not the case for all clients who seek help at Streetwork because of the limited number of beds for youth across the city, Vante said.

For L.S., who only wanted to go by a nickname to protect his immigration case, accessing a facility for young adults experiencing homelessness has been a great challenge. The 20-year-old from Mauritania, who arrived in New York in September, has been trying to access a longer-term bed in the youth system, and has been moved around from one shelter to another since facing various transfers due to stay limits.

L.S. used to take classes, he said, but having to move from one shelter to another so frequently has made it difficult for him to keep up with school, so he stopped attending. When his family calls him to ask if he’s in school, L.S. tries to make up a story instead. “Sometimes they call me, and I say, ‘yes.’ Because I don’t want to break their heart.”

“I want to be focused on school correctly without any stress,” he said. “I want to focus on my new life.”

Comment from DYCD was pending as of publication.

Galloway, of the Coalition for Homeless Youth, said that her group, along with mutual aid organizations, were sometimes trying to coordinate up to 40 shelter placements a day for newly arrived migrant youth, but there’s often no specialized place for them to go. “A lot of folks are out of resources, they’re out of beds,” Galloway said. “It’s extremely unfortunate the conditions people are having to bear in order to just get a bed in the shelter system.”

City Hall did not respond to a request for comment about unaccompanied minors.

At Floyd Bennett Field, a site for families with children, some advocates who have made regular trips to the site say they have encountered minors living in the shelter without a guardian, some of whom appear to be with their own children, or just accompanying their siblings. Paullette Healy is a parent who leads the Brooklyn Borough Response Team, a group of parent volunteers assisting asylum seekers. At Floyd Bennett, Healy was conducting intake interviews to determine the best schools for children at the shelter to enroll in, depending on their situation. She began looking into what high schools might even have daycare available so that minors with children could go to school and have childcare.

“What we discovered immediately at Floyd Bennett when we opened up that HERRC was that there was a large amount of people coming in that were young,” she said. “We gathered that they were between the ages of 14 and 18, and they were unaccompanied.”

For L.S., although he has found support at Streetwork, he worries about where he will sleep after his 30-day limit comes up next week and he faces eviction from his Bronx Shelter. He knows he will have to line up outside St. Brigid’s reticketing center in East Village to be placed in another shelter, despite the fact that there is a specific housing system meant for youth like him.

He awaits his eviction date anxiously and watches as other migrants collect bracelets, marking their place in line as they wait for shelter reassignments, numbers reaching the tens of thousands scribbled on papers strapped to their wrists. “That makes me afraid because I say, ‘Next week I will be on the street.’ ”

Update February 16, 2024: Following the publication of the article, the Director of the Coalition for the Homeless Youth said the organization misspoke when they claimed to have supported minors 12 and 13 years of age. We have corrected their statement.