As part of Documented’s new “Our City” interview series, we are speaking to prominent and influential New Yorkers who have deep connections to New York’s immigrant communities, some of whom are immigrants themselves. We ask them about how they made New York City their own, where they feel most connected to in the city, current projects, and more.

ADAMA BAH’S CHILDHOOD seems like that of a normal New Yorker, she tells me on a Friday winter morning at her offices in Harlem. She remembers going to school in Harlem, playing with her friends after class, and following the tune of the Mister Softee ice cream truck during the summers. She also remembers having to convince her father to send her to Six Flags with a school trip, which she remembers was a big deal.

“It was the three of us with my siblings, my Dad was like ‘I am not going to pay for that, $65 dollars is a lot of money.’ But now the ticket is almost like a hundred and something,” she says, laughing.

But going to the theme park was very special, because, as she puts it, “as immigrant parents they never took us there.” At Six Flags she visited Sesame Street and she remembers being mesmerized by the attractions of the beloved characters like Elmo and Big Bird. She also remembers riding her first roller coaster. “I was scared. And I was like nope, never again.”

But her life crumbled on March 24, 2005, when, at the age of 16, her Harlem apartment was raided by the FBI and the NYPD. The traumatic ordeal eventually became a documentary named after her. Adama, directed by Emmy-winning journalist David Felix Sutcliffe, was released in 2011 and included as an episode in WORLD’s America ReFramed series in 2016, due to its “timely perspective on the experiences of American Muslims at a time when their religion is being equated, by some, with violence and terror.”

Bah was detained for six months and her father was deported back to Guinea, from where she had emigrated, unknown to her, as an undocumented child at the age of 2. “This is my ankle bracelet box. It’s connected to my house phone. It comes with an ankle bracelet — and I can’t have it taken off until the case is over, which is very sad,” she says in a scene of the documentary.

In 2021, Adama wrote “Accused: My Story of Injustice,” further revealing how the federal government charged her with entering the country illegally, and had reasons to believe that she — at the age of 16 — was an “imminent threat” to the United States.

“Basically I was accused of being a potential suicide bomber. I wasn’t actually one but ‘potentially’ I could be one one day,” she tells me.

It is still hard to remember, she says, but it is Bah’s first-person experience navigating the immigration system and overcoming bureaucratic obstacles that has fueled her advocacy work to help her neighbors in New York City for the past 18 years with housing rights, food access and referrals to public programs.

Inside the offices of Afrikana in Harlem, an organization which she founded eight months ago to assist asylum seekers from African countries, she walks past numerous migrants with children who are engrossed in videos on their phones, tuned to popular songs such as “Baby Shark” and “Row, Row, Row Your Boat.” There are young men engaged in lively conversations about what they discovered in the city, a soccer game, or news about their immigration proceedings, there are many others who have come looking for the services that the organization has to offer. “We want to welcome them with dignity,” she says.

Can you talk about where you grew up?

I can’t believe I’m saying this. I live in The Bronx now. But I grew up in Harlem, I grew up in Manhattan. And I went to high school, elementary school, everything in Manhattan. It’s so bad that I’m so attached to Manhattan, that my kids go to school in Manhattan, that my kid’s doctors and dentists are in Manhattan. But of course, as you know, Manhattan is so expensive. And not affordable. I can’t afford it. So I had to trade that for The Bronx. Now, of course, The Bronx is starting to become unaffordable.

And you also have your own immigrant experience. How did you find out that you were undocumented?

I was told by ICE agents and FBI agents that I was undocumented. I did not really know what that really meant at that moment. I was like, what is this? It doesn’t make sense. They kept repeating it to me; I don’t know how many times.

I was really upset with my parents. I asked them — how could you keep a secret like that? It’s huge. What makes it worse is that you don’t qualify for anything. So you go from having the whole world to having nothing. So that shift was really, really shocking for me and my father when we were released from the detention center.

How old were you at the time, and why did they take you to a detention center?

So, my apartment was raided by the FBI and NYPD and they said I was undocumented and accused me of being a potential suicide bomber. I was not one, but [they thought] that I could eventually be one someday. I was 16.

And how long were you detained for?

I was in detention for six and a half months, which felt like years. It’s cold. It’s like a prison. The rules are strict and you cannot even move a certain way; there is a bedtime. It is as if you are not even human. I call it an ice box because that is what it really is. No one wants to talk to you. Everyone yells at you and everyone thinks that you are ignorant. You are a child and it is horrific. And then there are grown men and women talking down on you.

Detention is a hard place for anyone, especially if you are innocent. Because here you have grown men telling me you’re illegal, I had to explore my identity. Who am I? Am I Black? Am I African, am I Muslim? What is my identity?

I can see your experience helps you connect to the experiences of those who have been arriving. I also know you were one of the first people welcoming asylum seekers in the Spring of 2022. Can you tell me more about that experience?

I was already used to welcoming people. But I wasn’t prepared to see just people from South America or Latin America only. How we found out [about the buses] is that in Texas, NGOs that were placing migrants on the buses are actually grassroots. Unlike here in New York City, they [Texas] actually support nonprofit organizations doing this work at the border. They told us that there was the first bus coming. So we went with Team TLC and volunteers to welcome them with dignity.

We gave them food and COVID masks. The ones that wanted to leave were given tickets to leave. And the ones that wanted to stay were given shelter. I was letting people use my laptop so that they could connect with their loved ones.

“I had to explore my identity. Who am I? Am I Black? Am I African, am I Muslim? What is my identity?”

And then, nonprofits weren’t allowed to welcome migrants at Port authority any more?

A year later, yeah. So we were always welcoming them and, realistically, that made the city look bad. We had a whole social service system at Port Authority. We had legal, we had case management, we had everything. They stopped operations there but we kept still going.

How was the relationship with the city?

The city has been one of the worst partners, I think it was because they tried to reinvent a wheel that’s already invented to try to create services that already exist, instead of funding those services that exist. Their knowledge about asylum is horrible. I’ve been doing this work for 18 years, or I’ve been advocating for immigration reform, especially asylum, because asylum doesn’t make sense. It’s needed though. But now because you have a national crisis, everyone is like, this doesn’t make sense.

With any crises that happen, we are like, yeah, we have been telling you for years. Like housing advocates have been saying, you are going to have a housing crisis, and then they [the city] are like I don’t know what you are talking about.

Do you have any favorite memories about the city?

I have memories of the ice cream trucks and of Miss Margarita. We lived in the NYCHA projects and Ms. Margarita used to sell ice cream out of her apartment.

Well, she’s not alive anymore, but the health department would probably have shut her down. But we would go to her and say, hey can we get coco, can we get cherry? And she would stick her hand out with her frozen ice creams.

But nowadays you have the [ice cream] carts. We didn’t have that, we had Miss Margarita.

What is it that you like about New York City?

I always joke and say, I’m gonna be the last standing New Yorker. I am never leaving the city. I’ll go on vacation, but I’m always coming back.

I just love everything about the city. It’s my safe space, like, because I know everything. And I’m welcome here.

Can you tell me a little bit about Afrikana? How did it come to be?

I’ve always wanted to do my own organization, but I was always afraid. I was afraid of failure. But I’m so good at organizing that I took the leap of faith, but I didn’t have a name for the organization. So I have to thank the migrant crisis for the name because every time a Venezuelan, Ecuadorian, or Peruvian kept coming they asked me where I was from? So I would tell them that I was from Africa.

Then, they were addressing me by “la africana,” and I was like that’s a nice name for an organization. So I named it The African Woman. That is how it came to be.

That is so interesting. But you also have been in this space for nearly two decades right?

I’ve been doing this for 18 years and I am still considered to be new. And sometimes it feels like an insult.

What are some of the services that Afrikana offers?

Babysitting and occasionally nursery and singing.

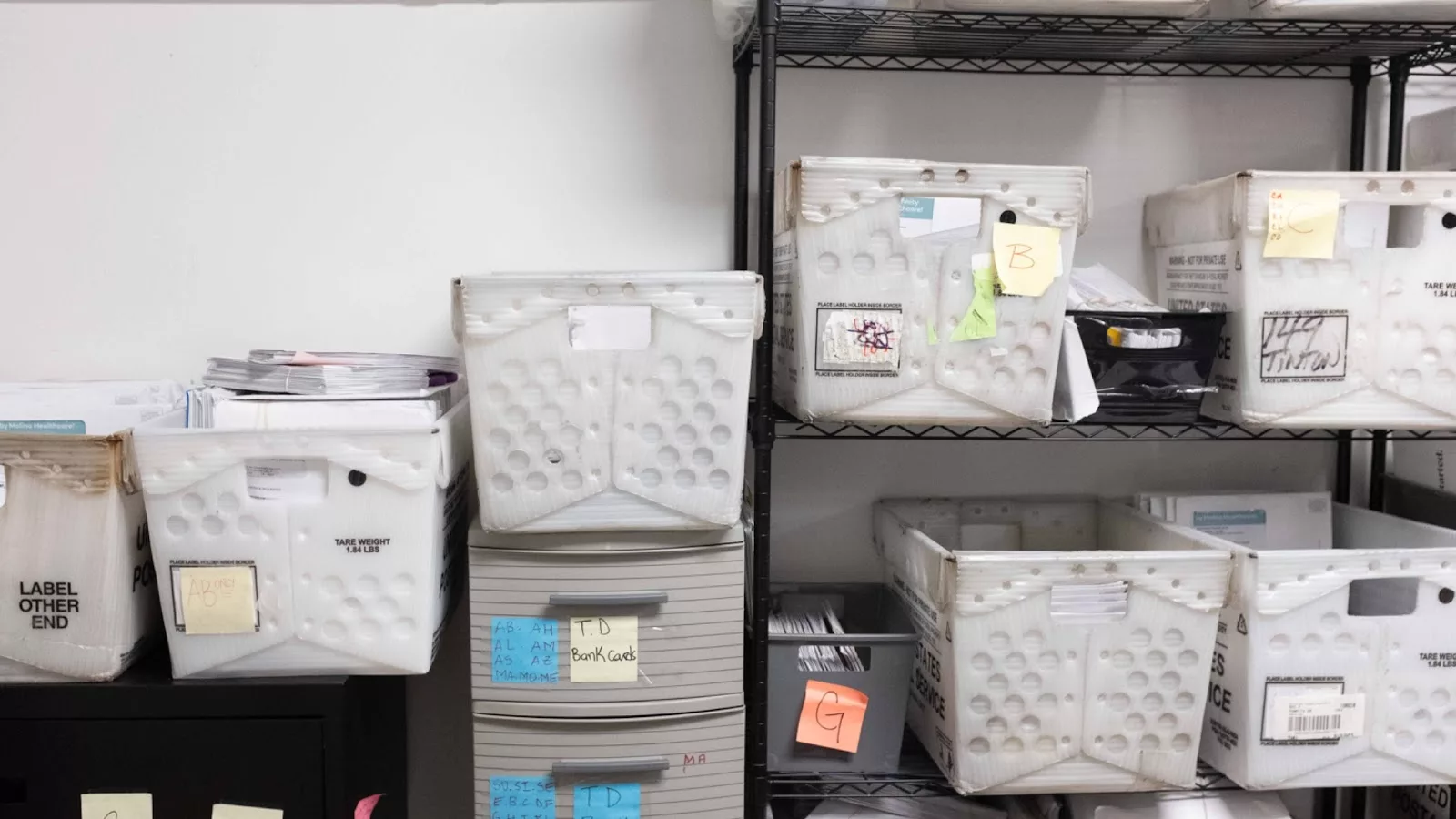

We offer a lot of direct services here. And the reason why I want to say direct services is because everywhere you go they are referring you to someone else, and then to someone else. The biggest demand we have right now is from people who receive the mail. I never realized that but this is how you become a human. Part of being a human is being able to just get your mail: your bank cards, your personal documents, and more.

That is one of the questions that I wanted to ask you. There is so much mail here.

There is no Amazon shopping here. It’s for people who have an emergency, who need certain things. We have insurance cards, IDs being delivered. There are also, unfortunately, people who receive tickets.

One of the things that I see coming up in our conversation is the cultural approach that you consider when offering the services.

We have to because if it was a city service, they would say “you guys are talking too loud” or something. For example, they [a group of women talking] are reminiscing right now, right here, because this is their first Ramadan away from home. They are laughing and they are having fun. It is important to humanize people, to understand where they come from, and allow them to be.

The other day there was a soccer game on TV between two African countries, so we played it. They were watching it as the asylum seekers were being seen for the services we offer. What we do here may not be ethical to some but in our cultures, it is ethical.

You are making them feel welcome.

Right. It was so funny during that soccer game because they were teasing one another whenever their country scored, playfully saying things like “oh, you have to leave, we are not servicing you at the office.” We were all laughing at that. We also have food to give out to the community but because it is Ramadan we are not doing it now.

“The biggest demand we have now is from people who receive mail. This is how you become human. Part of being human is being able to just get your mail.”

You are consuming a lot of difficult stories. How do you take care of yourself?

I take care of myself. I will be going to Florida on a girl’s trip. I go hiking in nature. People underestimate how necessary it is to release your energy in nature so much. Me and my kids drive everywhere to hike.

What are some of the ways in which people can help you?

We have a wishlist, and through PayPal. Sometimes I like to take the kids that have recently arrived to the grocery store to pick a snack, similar to those snacks that I used to get when I was growing up. They used to be 25 cents but now they are expensive, like 75 cents or higher.

This interview has been edited for concision and clarity.