Manuel says he would rather starve than eat the food at the shelter where he and his family live. Most days, he wanders the streets of New York asking strangers for work and food to feed his family. When he is unsuccessful, the family usually skips meals. He says he avoids the food because the city-provided meals make his family physically ill, giving them bouts of diarrhea, vomiting and spells of dizziness.

“I’d rather have two spoons of sugar and go back to sleep to avoid feeling hungry,” he said.

As an asylum seeker from Venezuela, he was given temporary shelter at the Redbury Hotel in Manhattan in October 2023, with his wife and four children, ages eight, 15, 17, and 18. His daughter, Mary, 15, who prefers being called by her family’s nickname, has been in the hospital at least two times in the past six months for dehydration, vomiting and diarrhea, Manuel said.

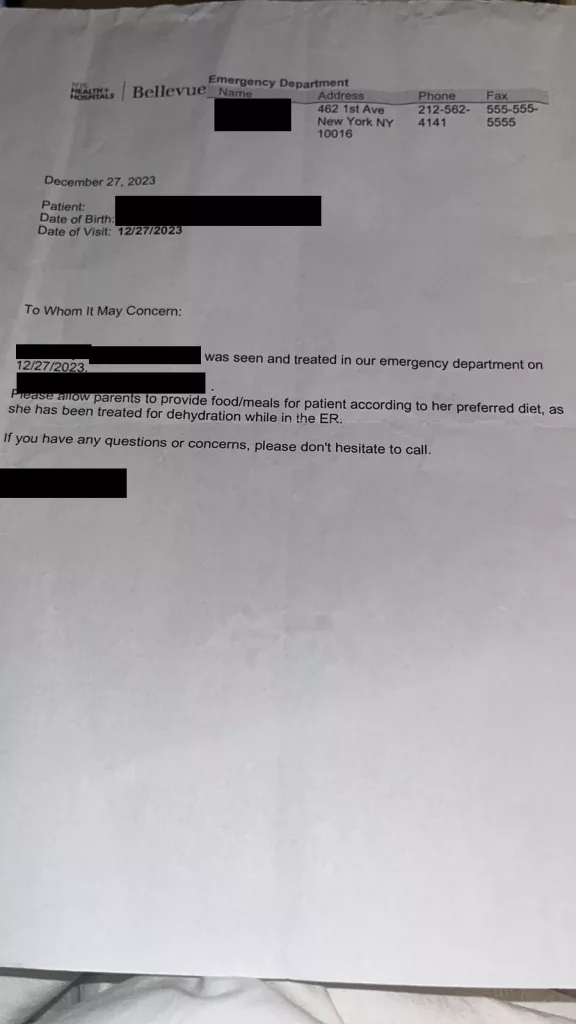

Last December, Mary left a trip to the emergency room with a stern written recommendation from the doctor: “Please allow parents to provide food/meals for the patient according to her preferred diet, as she has been treated for dehydration in the ER,” the hospital note read.

Still, the staff at the hotel won’t let the family bring their takeout meals inside their rooms, Manuel said.

Also Read: Immigrants Need More Food Pantry Access in New York

There haven’t been any changes in the meal options either, despite multiple requests made by the family and complaints made by at least eight people interviewed by Documented who have been living at the same hotel for months. Instead, every night they say the staff tosses out dozens of meals, many untouched by the residents of the building who fear getting sick from them, people interviewed by Documented said.

Manuel and his family are far from alone. In an unprecedented survey, Documented spoke with 58 asylum seekers, mostly Venezuelans, in 15 shelters managed by the Department of Homeless Services (DHS), across the five boroughs of the city.

They all described getting sick after eating the meals they received at the shelters, often resulting in stomachaches, vomiting, diarrhea, and occasionally, visits to the emergency room. Out of 58 people interviewed, almost half of the migrants said they don’t eat the meals at the shelter at all, while the rest ate the food occasionally. Likewise, nearly half of the migrants said their children have gotten sick after eating the meals, while five said they also got sick, and 10 said the meals were frozen when served.

Food safety experts and doctors say it is difficult to scientifically prove that the meals at the shelters are making asylum seekers ill, but dozens of shelter residents said that soon after they stopped eating the food provided to them by DHS, they felt better.

Also Read: Prepaid Debit Cards for Families of Migrants in NYC, Explained

Since the spring of 2022, more than 192,600 asylum seekers have arrived in the city in need of shelter and currently, more than 65,700 remain in the city’s care, according to data provided by DHS.

In response to the arrival of thousands of migrants, the city opened more than 221 emergency sites to provide shelter to migrants, according to DHS. A number of city agencies have overseen these shelters, including the Department of Homeless Services, the Department of Housing Preservation and Development, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and the Health and Hospitals Corporation.

Under New York City rules, the DHS must comply with specific requirements in shelters for families. Operators of these facilities are responsible for providing services that, at a minimum, include access to three well-balanced meals daily.

DHS policy also prohibits kitchen appliances that may be a fire hazard, such as hot plates, rice cookers, and microwaves, in shelters without in-unit kitchens, such as hotels where asylum-seeker families are staying. Instead, the department provides regular meal services that must comply with the NYC Food Standards, the agency said. These include frozen meals which are microwavable and supplies of baby food, baby formula, and milk for families.

“As we bring emergency sites online to provide shelter for tens of thousands of asylum seekers at a rapid speed and scale our incredible frontline staffers continue to work around the clock to provide essential services, including access to regular meal services that comply with robust NYC Food Standards,” Neha Sharma, a spokesperson for the Department of Social Services, which oversees the Department of Homeless Services, told Documented via email.

Vomiting, Diarrhea and Stomachaches For Days

In November, just a few days after being relocated to a hotel housing migrant families in Jamaica, Queens, Valentina, and Gabriela got sick after eating carrots and soy meat — the meal shelter workers gave them. During the middle of the night, they started vomiting, had diarrhea, and experienced severe stomachaches which lasted for the next few days.

While reviewing a thick folder with their medical records, their mother Antotatiany, who came to New York from Venezuela, said that between November 2023 and February 2024, Valentina, 16, lost 10 pounds. Her sister Gabriela, 9, lost six. The girls use their middle names for fear of being kicked out of the shelter. Antotatiany prefers to be identified by her family nickname.

After that first meal at the shelter, their lives changed. The girls say that they often feel dizzy and sleepy. “I used to do gymnastics, but now I’m too weak,” Valentina said. “Now, I’m even afraid of doing a pirouette and falling.” Gabriela usually falls asleep during class, according to her mother, who has been called by the school on multiple occasions.

The girls love to go to school. They have already made friends and see it as a safe space from the shelter where they live, Valentina said, who notes staff can enter rooms at any time, even as late as 11:00 p.m. But every time they get sick after eating shelter meals, they miss class and cannot see their friends or benefit from the meals being served at school.

The girls came to New York City with their parents in April 2022, where they were struggling to make ends meet in Venezuela, a country facing political conflict and a healthcare system plagued with shortages of medicine, lack of water, and basic health products.

Also Read: Migrant Children Face Trauma, Homelessness As They Seek Asylum in NYC

After a month-long trip from Venezuela, walking and taking buses north, they finally reached U.S. soil in April 2022. After five days in a detention facility, the family was flown to New York City by Catholic Charities, Antotatiany said. The family was placed in a traditional shelter run by DHS in Flushing, Queens, where they could cook and purchase their meals. The family was grateful for the housing the city provided them and was saving money to rent an apartment.

But in November 2023, they were relocated to a hotel for asylum seeker families with 224 rooms in Jamaica, Queens. Since then, the family, especially the girls, have struggled with the meals there.

Valentina and Gabriela knew from the first meal at the hotel that the food was making them sick. Still, whenever their parents couldn’t provide meals, they lined up with other asylum seekers to get microwavable food trays. In the hotel, they don’t have access to cooking facilities, so they either had to buy meals to take out or stick with the food provided to them.

But getting sick right after moving to a new country is not uncommon, a pediatrician, a foodborne expert, and a biological engineer, told Documented. When people move continents, their microflora changes and there might be ingredients in the food that their bodies are not used to consuming, Dr. Manuela Orjuela-Grimm, an epidemiologist and pediatrician at New York Presbyterian Hospital, explained.

“If it’s just individual children, it doesn’t mean that the problem was the food per se, it may just be a mismatch between the food and what they’re able to tolerate,” Dr. Orjuela-Grimm said.

Dr. Orjuela-Grimm said she’s heard from colleagues who also research child migration that some asylum seekers have received spoiled meals in transit camps in some Central American countries. This may offer some context for why the families are worried that they may be getting unsafe food, she said.

“It’s encouraging that they stopped eating those meals and they stopped getting the symptoms,” Dr. Orjuela-Grimm said. “But there could be lots of things behind that.” Each case needs to be looked at individually, she said.

“Spoiled, nutritionally or medically inappropriate or raw”

Facing mounting complaints and news reports about poor food quality and waste, the DHS sent an email in early February 2024 to shelter staff hired for temporary positions with guidance on food intake, rotation, discard, ordering, storing, and handling at the shelters.

Shanise Joseph, a former night shift supervisor hired by a temporary agency to work at the Le Jolie Hotel in Brooklyn between April and July 2023, said that asylum seekers described the food as “nasty, tasteless, and stale.”

Joseph received the email after she left that job, but she worked at the hotel, she had never received such detailed instructions about how food was supposed to be handled, other than making sure the quantity of meals received matched the orders. If there were any issues with the food afterward, there was no paperwork to document these unless an ambulance or an emergency response team was called, Joseph said.

Also Read: What the 18-Month TPS Extension Means for Venezuelans in New York City

The email sent by DHS specifies that staff should not throw away people’s food such as take-out, prepared meals, and snacks. “Clients are allowed to have this food on site,” it reads.

But in a dozen interviews with asylum seekers at several shelters, they claim that they are often restricted from bringing food to their rooms, even if it is already prepared or packed. They are told by staff that food must be consumed at the dining hall, or otherwise, it will be tossed away.

At least a dozen of the migrants interviewed also claimed that the shelters didn’t have enough microwaves for the number of families staying in the facilities; thus, the reheating times were sometimes restricted and families ended up with frozen food. According to DHS, there is no time limit on the use of microwaves.

Representatives across the city have also brought their worries to DHS and Mayor Eric Adams’ administration.

“At times, residents of shelters across the city have been served food that is spoiled, nutritionally or medically inappropriate or raw,” said Councilwoman Julie Menin at a December 2023 City Council meeting reviewing the shelter food contracting. “Many migrant children have difficulty adjusting to the food in shelters which has led to nausea, vomiting, and other gastrointestinal issues. Some have even had to be hospitalized.”

Councilwoman Julie Won added that she has received calls from medical professionals, teachers, principals, and parents concerned about the food quality and children who are malnourished, having rapid weight loss, and getting sick from the food.

At the December City Council meeting, Councilwoman Won also pointed out that the food at one shelter in Long Island City was being laid out on tables in dining areas with no refrigeration for hours.

When asked about the concerns asylum seekers have raised about the meals, Sharma, the spokesperson for the DHS, told Documented that protecting the health and safety of their clients is a top priority, writing in a March 19 email that: “As we have always done, DSS-DHS complies with food regulations across sites while ensuring that all our clients are receiving a consistent standard of services,” the spokesperson wrote.

Yet when Documented spoke with Manuel, he said that the “food is not appropriate for human consumption.” In many cases, his 15-year-old daughter Mary would skip meals, which left her constantly feeling dizzy and weak.

Food providers have health and labor violations

Council members have been questioning the quality of the meals from the food providers, and a review of public records found that the food companies contracted by the DHS and subcontracted by organizations running the shelters have manufacturing violations that pose a risk to the health and labor violations.

Also Read: Pregnant, Sick, Homeless and Afraid: Bronx Fire Survivors Say the City is Not Doing Enough

The city comptroller’s office released a report in November 2023 that addressed existing issues within the emergency procurement process and found that city agencies “are not doing enough to ensure that vendors and subcontractors have been properly vetted, tracked, and evaluated.” The report analyzed emergency contracts that included shelter, meals, medical care, and legal assistance to new migrants.

DHS declined to address questions about how the department ensures that contractors and subcontractors are properly vetted and their performance is evaluated.

As DHS is still taking some steps to address the issues raised about the meals, asylum seekers struggle.

After more than four months of not being able to digest the meals, and episodes of diarrhea, vomiting, and stomach cramps, Antotatiany and her two daughters, Valentina and Gabriela try to remain resilient.

Still, they know there is little they can do. Their only hope is to be able to earn enough money to rent an apartment in the city and cook their meals.

“We’re spending money on takeout meals every day,” Antotatiany said. “At least if we cook and eat at home, we are able to save, but spending on takeout meals has made it impossible for us to save enough to cover the broker fees, but in the name of God we will figure it out.”

The Toni Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism contributed to this report.