On a Saturday morning, the building at 62 Mott St. in Manhattan’s Chinatown resonated with the joyful sounds of children singing and laughing.

A Chinese music class was in full swing.

“Love you, love you, you’re my whole universe,” sang a group of children aged 4 to 6, arranged in three rows. Their faces beamed with excitement as they raised their hands over their heads to form iconic heart shapes, following their teacher’s energetic movements in a lively rendition of Chinese nursery rhymes.

These children, students at the New York Chinese School (NYCS), were preparing for the upcoming cultural performance at the school.

Founded in 1909, NYCS is the largest Chinese school on the East Coast and one of the oldest Chinese schools in the United States.

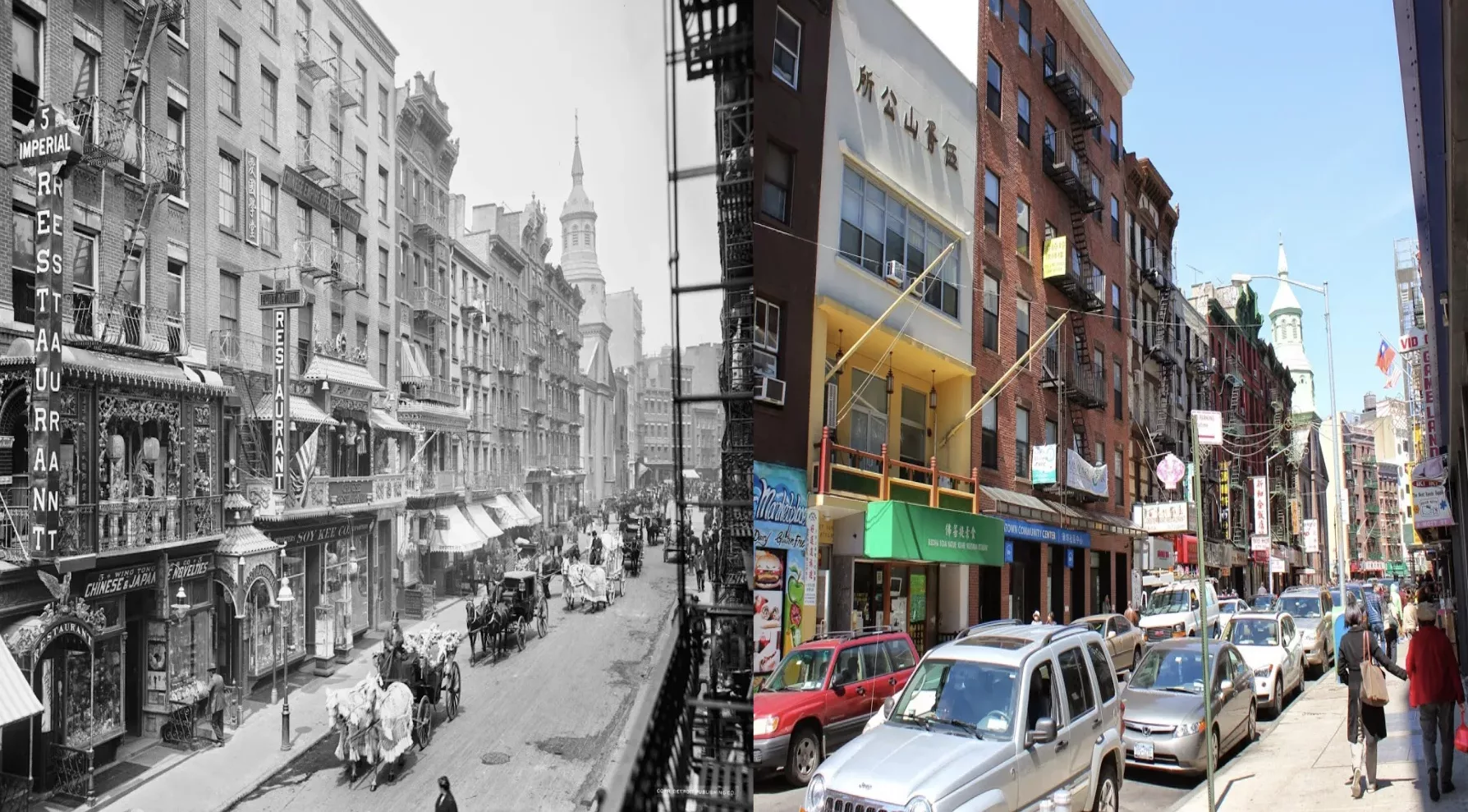

Over the past century, NYCS has experienced its share of ups and downs but has continued to uphold its original mission of preserving and promoting Chinese culture while meeting the changing needs of the Chinese community by expanding its services and resources. The history of the NYCS is a microcosm of the education history of Chinese immigrants in the U.S., reflecting changes in the demographic of Manhattan’s Chinatown, the evolving needs of Chinese immigrants, and their efforts to balance preserving their cultural roots with adapting to the new environment of their new country.

To learn more about this legendary and historic institution, Documented spoke with Jennifer Wang, the current and 19th principal of NYCS, along with a parent of one of the students.

The school in Chinatown’s “City Hall”

When talking about NYCS, one cannot overlook its location within the New York Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA). Many liken the chairman of CCBA, one of the oldest community organizations in Chinatown, to the “mayor” of Chinatown, and the New York Chinese School is the school situated within Chinatown’s “City Hall.” The school is one of the 60 associations affiliated with CCBA, and its establishment and development are closely tied to the years of support and assistance from CCBA. Located at the CCBA building, the school has multiple classrooms and a gymnasium.

In the mid-19th century, the California Gold Rush attracted thousands of Chinese immigrants seeking new opportunities. However, the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 left around 20,000 Chinese laborers jobless. Many relocated to other U.S. cities, particularly New York. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 further worsened their plight. Against this backdrop, the CCBA was founded in 1883, serving as a sanctuary for Chinese immigrants in New York, fostering mutual support and providing access to social services and resources.

Then in 1905, the Qing Dynasty abolished the imperial examination system, promoted the establishment of schools, and planned to develop overseas Chinese schools, according to the archives provided by NYCS. In December 1906, Qinggui Liang, a cabinet member of the Ministry of Education later heralded as the “pioneer of Chinese education in North America,” helped establish 14 Chinese schools across North America.

NYCS was born out of this initiative. During Liang’s visit to New York, he discussed with Huanzhang Chen, the chairman of CCBA at the time, about the significance of overseas Chinese preserving and promoting their Chinese heritage, a sentiment that resonated deeply with Chen. Because it was challenging to teach Chinese culture to Chinese children away from their homeland, Liang recommended that an overseas Chinese school be set up for Chinese culture promotion. Thus NYCS was established with full approval by all parties. Under Chen’s advocacy, NYCS opened on September 15, 1909.

“God loves this school”

As with many things, the school’s beginning was difficult. The school was temporarily run at 21 Mott Street in Manhattan, the Baptist Church, having only about 20 students. Raising funds was the urgent task at hand. CCBA decided to allocate $250 per year from the organization to back up the school operation. Meanwhile, community members actively raised funds for the school. According to the school’s historical records, in 1929, the Chee Kung Tong (The Chinese Free Mason) Headquarter in New York, one of the NYCCBA’s affiliated organizations, sent members to the CCBA in San Francisco to fundraise for setting up NYCS.

The school later moved to 13 Doyer St. in 1913. As the number of Chinese in New York rose, and the number of students in NYCS increasing as a result, CCBA contacted the city government in 1929 to purchase the building of PS 108 located at 62 Mott Street. In 1962, NYCS was officially registered as an absolute charter school and approved by the New York State Department of Education. That same year, the school moved into the newly reconstructed CCBA building where it has remained ever since.

“I think God loves this school, and we also operate it as a non-profit organization, adhering to Christian principles,” said Principal Wang, recalling how the school started in a temporary space at a local church and received tremendous help and support from the Chinese community since its founding.

Wang mentioned that over the years, the school’s operations have relied on tuition and donations. For instance, the initial donation to start the school’s library came from Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, the first Chinese woman to graduate with a PhD in economics in history and a prominent Chinese community activist. Chinese community organizations and businesses are also major donors to the school.

To meet the evolving needs of the Chinese community, NYCS started offering weekend and summer classes in 1963. Today, the school primarily teaches Chinese to students aged 4 to 18 and also provides Adult Chinese and Cantonese classes. Additionally, it offers tutoring in various academic subjects and extracurricular activities, such as adult English classes, United States Citizenship Naturalization classes, piano, violin, dance, painting and computer classes.

“We offer affordable tuition for weekend and after-school programs, which helps many working class families take care of their children so they can focus on their work,” said Wang. The curriculum is well-received by many parents. According to Wang, the school’s enrollment peaked at over 2,000 students per year before the pandemic.

Despite expanding its programs over the years, the school still adheres to the four moral standards from ancient China: “礼、义、廉、耻,” which represent propriety, justice, integrity, and honor. The school hosts its Confucius Ceremony every year. It would send the Crimson Kings Drum Corps, its award-winning marching band, which stopped operating since the pandemic, to attend important festivals or cultural events in the Chinese community.

“It takes ten years to nurture a tree, but a hundred years to nurture a person,” Wang quoted a Chinese idiom. She emphasized that the school’s mission is not only to teach students languages but, more importantly, to impart Chinese traditions and cultural heritage and instill in them a sense of giving back to the community.

Over the past century, the school has witnessed numerous outstanding alumni returning to serve the Chinese community, including three former or current principals of public schools in Chinatown, as well as doctors, lawyers, and other professionals.

As the school grows, it also attracts many students with or without partial Chinese descent. “I believe that in the era of globalization, learning a second or third language is a trend,” said Wang. She noted that at least 30% of the students at the school are non-Chinese or of mixed Chinese descent.

Lynn Berat, a mother of nine and resident of Lower Manhattan, expressed her deep affection for NYCS.

“We have associated with the school for about 20 years,” she said. “We don’t have any Chinese background, but the school feels like our home away from home. My daughters really love it. Everyone has always treated us wonderfully, and the current principal is fantastic.”

She highlighted the main reason for sending her daughters to NYCS as the importance of language learning. All of Berat’s daughters are either alumnae or current students at the school. Those who graduated from NYCS are pursuing majors related to China or Chinese. Her eldest daughter, Lindsay, who began studying at the school at the age of four, is now a doctoral student majoring in Chinese Studies at Oxford University. “For us, it has become our way of life. It’s not just a passing interest in Chinese; it’s deeply meaningful,” Berat added.

115-year-old school faces pandemic and post-pandemic challenges

However, the school is grappling with a significant decline in student enrollment and budget due to demographic changes in Chinatown and the impact of the pandemic. It is now facing challenges in its recovery efforts.

According to Wang, one major backdrop is that in recent years, Chinatown has seen an aging population, with many new immigrants flocking to Flushing and Brooklyn. Most parents opt to enroll their children in schools and tutoring classes near their homes, leading to a significant decrease in school-age children in Chinatown. Additionally, new immigrants prioritize their children’s adaptation to an English-speaking environment over Chinese education.

When the pandemic hit, the situation for Chinese schools in Chinatown was so dire that some couldn’t recover from the impact and announced closure this year. Many students either opted for virtual classes or enrolled in Chinese schools in their neighborhoods, and a significant number of them have yet to return to the school since the pandemic. Wang noted that the current enrollment is about 400 students, compared to the peak of 2,000 students before the pandemic.

The decrease in student enrollment directly leads to a decline in revenue. Facing budget constraints, the school suspended the operation of its marching band, which was founded in 1954. Additionally, teachers and volunteers at the school have taken on the responsibility of cleaning the classrooms to save costs.

Wong highlighted that the school has been providing classes with affordable tuition over the years, typically around $290 for Chinese classes per semester. Annually, the school offers scholarships to graduates, ranging from $100 to $1,000. “In general, we offer free language programs for all our students,” said Wang. She said the scholarship was sponsored by Consultant Eric Ng of the CCBA and Chin Sun Wong, the founder of Wonton Company. They have jointly established the graduation incentive fund.

The school has implemented several measures to help increase enrollment and improve education quality. These include establishing partnerships with universities in NYC to recruit graduate volunteer teachers, launching online marketing targeting the tri-state area, and continuing online programs. “We have been serving the community for 115 years, and we didn’t stop for a single day during the pandemic. We want to continue that commitment,” said Wang.