Early this year, shortly after arriving at a refuge for migrants in Mexico City, L.R. was kidnapped.

The men who held him hostage, requested a ransom from his family back in Caracas, Venezuela. The kidnappers were made who they were clear, L.R. — his initials, to protect his identity — told Documented in Spanish. “‘You know who got you? Tren de Aragua got you’,” they told him.

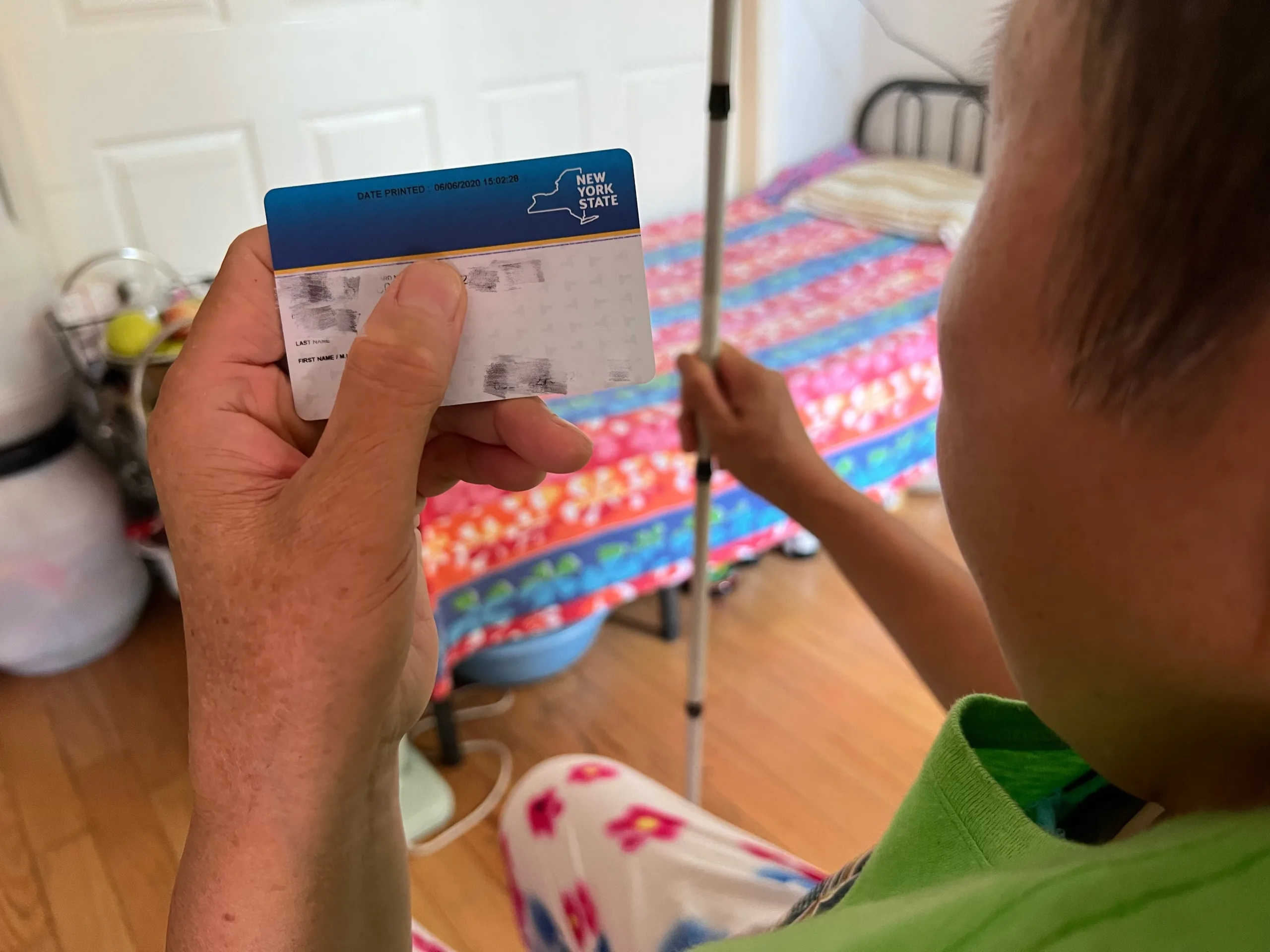

Tren de Aragua, a gang formed some 15 years ago in a prison in Aragua state, Venezuela has been linked to criminal activity outside Venezuela, but L.R., who is now in New York City, feels secure. He has not heard of any gang members present in the City. “We are safe here; we are good,” he said.

In the past year, conservative media outlets have spread the often misleading or incorrect news of the Venezuelan gang arriving in cities across the United States and wreaking havoc. Former President Donald Trump referenced unconfirmed reports that the gang is active in Aurora, Colorado, at the presidential debate. Republican lawmakers have portrayed the gang as a national security threat.

But, New York advocates and attorneys are wary of this narrative, which recalls the fears of Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13, the transnational criminal organization that was started by Salvadoran immigrants in Los Angeles in the 1980s. Former president Trump stoked fears of the gang early in his term as president, which resulted in the criminalization of Latin American youth, leading to deportation, denial of rights, and discrimination.

The supposed Tren de Aragua threat has nonetheless taken hold. In a letter to President Biden, almost two dozen Republican legislators led by Marco Rubio described Tren de Aragua as “an invading criminal army” that could “unleash an unprecedented reign of terror” in the United States. The gang was responsible, they added, for the “rapes of multiple children” — an unsubstantiated allegation. Texas U.S. Representative Tony Gonzales, echoing the rape claim, said that Tren de Aragua was “the epitome of evil.” In July, the Biden administration labeled Tren de Aragua a transnational criminal organization and offered a $12 million reward for information leading to the arrest or conviction of its leaders.

“When you use the word gang, it’s really scary and people don’t want to go into the nuances behind it,” said Camille Mackler, the executive director of Immigrant ARC, a coalition of legal service providers in New York. People labeled as gang members are overwhelmingly young men of color or of immigrant background, she said. The gang label has been used as “a political talking point” that then was corrupted into a pretext to incarcerate people of color and unjustly deport adolescents with no criminal record, Mackler said.

Under the Trump administration, ICE deported thousands of Central Americans associated with MS-13, often based on flimsy evidence. Today, the same information-sharing agreements that allowed ICE to deport individuals based on the gang databases of local governments remain in place, Mackler said.

A person can be labeled a gang member for their appearance, neighborhood or acquaintances. Individuals have landed in the database because of a tattoo, a drawing, a hat, a hand sign, or using a certain word.

In June, the 19-year-old Venezuelan Bernardo Castro Mata, was caught riding his moped against traffic in Queens. During his arrest, he allegedly shot at two officers, hitting one in the foot.

Investigators claimed that Castro Mata is a Tren de Aragua member because of a tattoo on his arm — a clock attached to an anchor — according to The New York Post. However, the think tank InSight Crime states that tattoos are not an identification symbol for Tren de Aragua members, as they are for groups such as MS-13. Police also linked Castro Mata to moped muggings in Queens, although Queens District Attorney Melinda Katz did not charge Castro Mata with other crimes than the assault on the police officers.

Despite the lack of evidence that the gang is active in the city, the NYPD has used it to call for the preservation of its controversial gang database. The “rise of Venezuelan, Ecuadorian, and Colombian gangs has required us to adapt our strategies,” NYPD assistant chief Jason Savino said in August. “The gang database is crucial in this regard,” he added. The problem is that the database has serious flaws, advocates and independent monitoring groups have said.

In numerous instances, people were listed in the database for a singular social media post; in others, entire public housing developments were considered “known gang locations,” according to a 2023 report from the NYPD’s Office of the Inspector General. The report confirmed that 99% of the “gang database,” which includes tens of thousands of names, are people of color. The NYPD did not respond to a request for comment.

These labels may lead to deportation for Venezuelans, as it happened with alleged MS-13 members, who were removed by the thousands from 2017 to 2020, suggested Alexander Holtzman, director of the Deportation Defense Clinic at Hofstra University in Nassau County. Any administration, he said, “can once again use dangerous rhetoric to try to label immigrants, particularly young Hispanic males, as dangerous.”

The NYPD’s guidelines for possible gang tattoos is broad and includes common imagery like crowns and stars. It also currently associates the American Sign Language (ASL) gesture for “I love you” — the index finger pointing upward and the thumb and pinky extended — with Tren de Aragua. Lawyers and advocates are worried this broad definition could ensnare more people.

South Bronx Councilmember Althea Stevens re-introduced a bill last April that was endorsed by 19 Councilmembers and dozens of grassroots and civil rights organizations to abolish the database and prohibit a future one from being formed. The NYPD gang database, she said, subjects “black and brown” youth to “unclear criteria” and sweeps up too many “innocent people.”

Critics have used Castro Mata’s case to lambast the bill, criminalizing Venezuelans. Joseph Giacalone, a retired NYPD sergeant and an adjunct professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, told the New York Post in August that the Councilmembers trying to erase the gang database “would rather see cops shot in the street and New Yorkers robbed at alarming rates than to use common sense.” Police officers, he said, were “targeted by the recently immigrated Venezuelan gang members.”

However, Mayor Eric Adams stated last May that City officials were “not 100% sure” about Tren de Aragua’s presence in the City. “We may find one or two members,” he added in an interview with Telemundo, “but we want to see how extensive it is.” Actually, it has been years since the City was this safe. As of July 2024 — the latest month for which figures are available — the City registered the fewest number of year-to-date shooting incidents and shooting victims in the previous five years.

Niurka Meléndez, founder of Venezuelans in Action (VIA) — a nonprofit founded in 2016 in New York that hosted last year meetings for over 12,000 displaced Venezuelans — has informally learned that malandros (thugs)from her home country–—or folks with a criminal record— are indeed in New York. However, Meléndez stressed that she had not heard of Tren de Aragua being active as a gang in the City. Instead, she has perceived that “hate speech, xenophobia, and discrimination against Venezuelans are growing at a breakneck pace.”

MS-13 then, Tren de Aragua now

While the Mayor’s Office has yet to confirm if any Tren De Aragua members were present in New York, one of the top federal agencies for investigating transnational criminal organizations could not verify either any Tren De Aragua activity in the City.

“HSI New York is aware of recent violent crime arrests involving individuals allegedly associated with the Tren de Aragua street gang,” said Stephanie Pagones, the spokesperson for Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), in a statement to Documented. According to Pagones, HSI New York’s Violent Gang Task Force (VGTF) — also composed of the New York City Police Department and the New York City Department of Correction — is monitoring the situation.

In May, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) announced the arrest of an alleged Tren de Aragua member in Long Island — Johan José Cárdenas Silva, a Venezuelan national. Wanted by Peruvian authorities for conspiracy, assault and aggravated theft, Cárdenas Silva was charged in New York with criminal possession of a loaded weapon and a controlled substance with intent to sell. He was placed in deportation proceedings.

Cárdenas Silva’s case was the second action announced by ICE on an alleged Tren de Aragua member in the U.S. interior after a detention last March in Chicago. The suspected murderer of Laken Riley in Georgia last February was loosely associated with Tren de Aragua. Another case involves the unfounded claim that Tren de Aragua members took over housing buildings in Aurora, Colorado, due to a viral video of armed men in a staircase. Aurora Mayor Mike Coffman, a Republican, refused to confirm the men were Tren de Aragua members, while neighbors deny the presence of the gang in the buildings, saying they are “victims more of landlord negligence than of criminals.” Nonetheless, candidate Donald Trump has embraced the rumor, mentioning at the presidential debate on Sept. 10 that recent immigrants “are taking over the towns.” He said: “Look at Aurora in Colorado.”

It remains unclear, however, if any of the alleged Tren de Aragua members charged with crimes were operating as a gang cell or coordinating actions with its leaders—in case they do belong to the criminal organization.

As well-established gangs already control criminal U.S. markets, “Tren de Aragua appears unlikely to make substantial inroads in the United States,” concluded a report issued by InSight Crime in April.

Despite the rhetoric, court records, ICE public statements, Mayor Adams’ claims, the own NYPD crime statistics, and the testimonies from displaced Venezuelans do not show that Tren de Aragua operates as a gang in the City.

“Inside the shelter, we have not had any incidents. As immigrants, we all come to this country as part of the same struggle,” an asylum seeker identified as C.B. — his initials — told Documented in Spanish. Outside an East Harlem shelter, along with his wife, C.B. said they’d heard of Tren de Aragua in the news. “But where we live,” he added, “we have not seen those things.”