As part of Documented’s new “Our City” interview series, we are speaking to prominent and influential New Yorkers who have deep connections to New York’s immigrant communities, some of whom are immigrants themselves. We ask them about how they made New York City their own, where they feel most connected to in the city, current projects, and more.

I MET EDWIDGE DANTICAT a week after the U.S. election. She writes in her new book, “We’re Alone,” that “…all my stories reaffirm my belief that being human means having to keep beginning again.” The quote seems fitting to reflect on during this time, having been thrown into the reality of an election outcome once thought unthinkable because hope made many believe so.

During the 2024 elections, President-elect Donald Trump falsely claimed that Haitians were eating people’s pets in Ohio, among other falsehoods about immigrants. The claims echoed the stigmatization Danticat faced as a child in the early 1980s, when all Haitians were often falsely assumed to have AIDS. At public junior high school in New York, Danticat and other Haitian students were bullied and accused of having “dirty blood.”

Trump’s anti-Haitian remarks were similarly nonsensical, and led to real-life consequences including at least 33 bomb threats against the Haitian community in Springfield, Ohio. “This very specific anti-immigrant focus, this othering, for a lot of young people, it’s going to be jolting,” she told me. “I mean, they are afraid. But, we have no choice but to turn inwards, to community, find solace in one another and really brace for what’s coming ahead.”

Born in Haiti, Danticat moved to New York at age 12 to reunite with her parents who had each immigrated eight and 10 years earlier to break free from poverty and look for work. Her father worked as a cab driver, her mother in factories, both striving to build a better future for their kids. Later, Danticat would settle with them in East Flatbush, where her father, a deacon, often brought her along on visits to the Brooklyn Navy Yard to help detained Haitian refugees.

“The church was a central home,” she said while we sat to speak at a book store. She recalled how church members supported each other by co-signing loans and writing letters for immigration papers. Many residents in Danticat’s childhood building at Westbury Court in Brooklyn were also from her church, and on Sunday afternoons, she said they would gather for potlucks. “It was a real community, much needed at that point.”

She told me that in bracing for the coming years under President-elect Trump’s administration, community too would be needed most. Danticat’s articulation of the experience of migration and the description of the Haitian community in the U.S. has helped many recognize themselves and their own experience of migration in a way that’s rare. She is the author of many award-winning books, including her memoir, “Brother, I’m Dying,” which was the winner of a National Books Critics Circle Award and a finalist for the National Book Award. She currently teaches in Columbia University as the Wun Tsun Tam Mellon Professor of the Humanities in the African American and African Diaspora Studies Department.

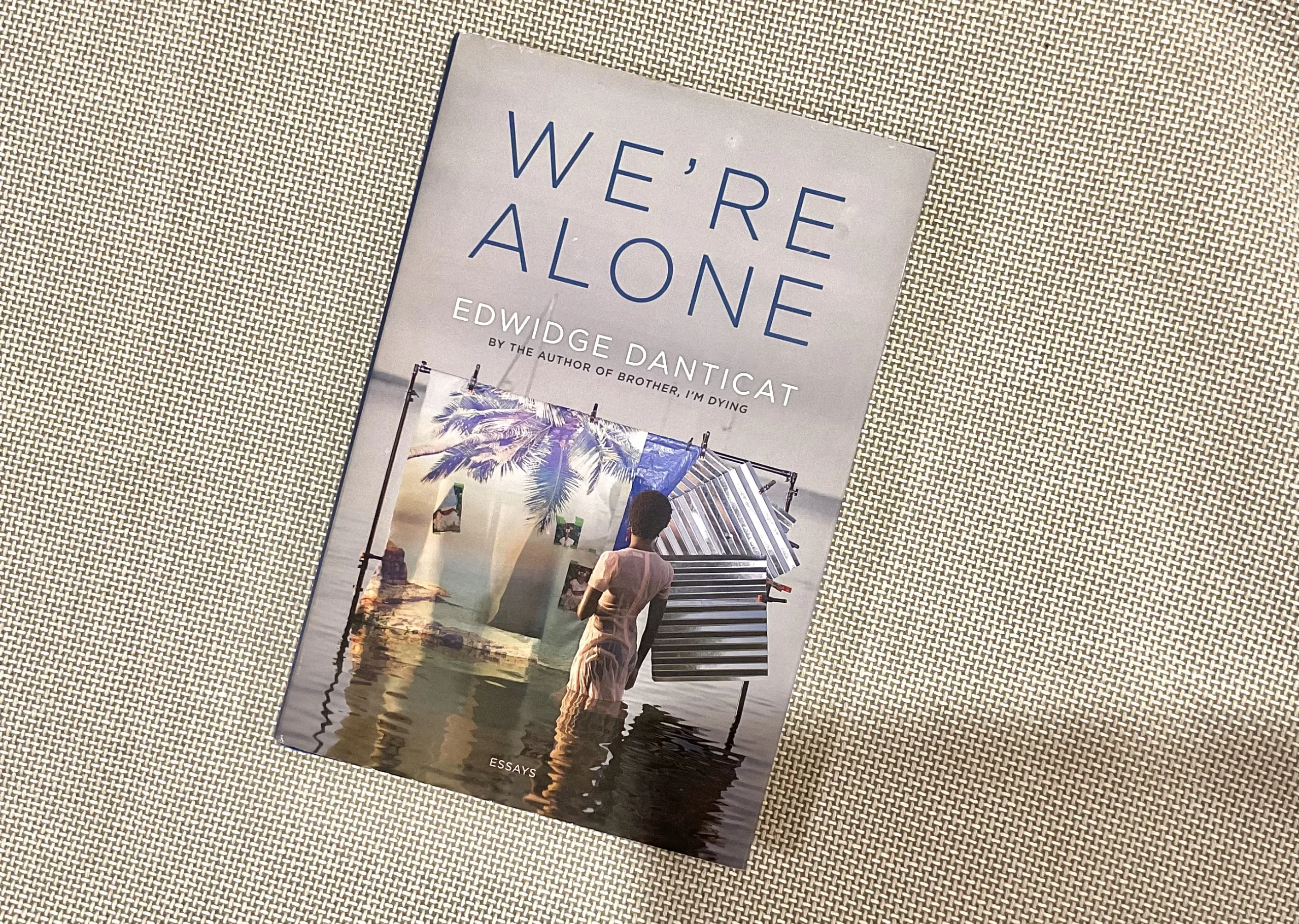

Thank you for writing this book. As you aptly said in it, beginnings are harder than endings. I sometimes like to start from the cover of the book. Why did you choose Widline Cadet’s photograph for it, and how would you say it’s connected to the eight essays you wrote in “We’re Alone?”

During the pandemic in 2020, I was asked to write an essay about Widline Cadet’s work and a lot of her photographs were outdoors. They were images of people embracing, touching at a time when we were all inside, and so I remember trying to address the images, just really focusing on this longing for touch. Also, she’s Haitian American, and I’m Haitian American, and there are commonalities of knowing a lot of our relatives through photographs once we migrated. I was very moved by her work and […] I saw that photograph of the young woman with all those photographs within the photograph, standing deep in water reflecting with that sink, which is material that we make roofs with in Haiti. There’s so much water in “We’re Alone” you know, water as flood, water as history, water as memory.

Had the dehumanizing use of Haitians in Ohio as a political tool during the 2024 election occurred before “We’re Alone” was published, I imagine it might have been a focus of critique. There’s a line in your book that seems relevant to it: “Xenophobes often speak of migrants and immigrants as though they are an invasion force, or something akin to biological warfare.” I wonder what your assessment of Trump and Vance’ weaponization of false claims against Haitians as a political tool in this election is.

Even though, as Haitians and Haitian Americans we are used to xenophobia, stigmatization, not just here in the United States, but different places around the globe, it felt so particularly singular, like being used as a proxy for xenophobia, being used as a proxy for for anti-blackness and we saw what the results were. There were bomb threats. There were people who couldn’t leave their homes. I think that’s something, even after the election is concluded, that’s not going to leave people’s minds. Especially with the constant drum beat of mass deportations. So it feels particularly dangerous in this electoral cycle because the othering, the dehumanization, the stigmatization was so visceral and the fact that it was spread around social media, it’s imprinted in people’s minds in a way that makes Haitian immigrants particularly vulnerable for the next four years. When people talk about being afraid, sometimes, it’s made fun of, you know “you’re snowflaking.” But if an election was won with your face in that kind of othering, it can be very dangerous. Because it worked this time, it’s likely to become an imprint of how people win elections. Not just in the United States, but around the world.

Yes,unfortunately, it’s how a lot of politicians, especially here in the U.S., have won elections in the past, too.

You’ve said before that you write for the person you were at 15, for the girl looking for the image of herself. There’s a whole generation who saw for the first time what it means to experience anti-immigrant politics, who tried to make sense of it and I wonder what you’d say to them about the reality we all just lived.

I think we’re all still processing what just happened. A lot of things happened, right, but this very specific anti-immigrant focus, this othering, for a lot of young people, it’s going to be jolting and they’re going to be afraid. I mean, they are afraid. But, I think we have no choice but to turn inwards, turn to community, find solace in one another and really brace for what’s coming ahead.

Thankfully, there are organizations in the community, and two of the ones that I’ve known and participated with over the years are Haitian Women for Haitian Refugees, the Haitian Bridge Alliance, and others. We’re going to really need the community to gather and support the most vulnerable people in whatever ways we can.

When people talk about mass deportations — this past week, I’ve been thinking about this because my parents were undocumented when they came here, they came on tourist visas and stayed and eventually they got to gain status, which allowed them to send for us in Haiti.

But my mom was arrested twice in factory raids, once when she was pregnant with one of my brothers, and she was detained for several days as well. So we’ve seen some of this before, but on this scale, with the resources, with the people that are being hired to run Homeland Security, it’s going to be very tough. We’re going to have to turn to each other. Everyone is going to have to be vigilant to find how we can support and protect the most vulnerable amongst us. In the past, during my mom’s time, churches stepped up, community groups stepped up. I think we’re going to need that level of grassroot organization.

“This very specific anti-immigrant focus, this othering, for a lot of young people, it’s going to be jolting. … I mean, they are afraid. But, I think we have no choice but to turn inwards, turn to community, find solace in one another and brace for what’s coming ahead.”

What was it like moving back to New York City to live here full time again having spent the better part of your teenage years here before moving to Florida, living there for two decades and then returning here? Are there ways in which you had to make yourself feel at home again in the city?

I lived in Florida for 22 years from 2002 until last year, but my mom was living here, so I was back quite a bit. My brothers are here, so I never felt like I left the city. But one thing that was incredible was to get to Newkirk Avenue and see it now being called Little Haiti. One of the things that wasn’t even considered in the stigmatization of Haitians and Haitian Americans during the election cycle was the contribution of Haitians and Haitian Americans in the community. So the fact that the stop was now called Newkirk Ave-Little Haiti, which was my train stop from the time I was 14 all through college, I would get off there and walk home, that was very moving.

The life my brothers and I now have came at a great sacrifice from my parents, like a lot of immigrant parents. You asked earlier about young people. I think of young people. I’m 55 years old now, and I was 12 to 14 years old when they were saying Haitians had AIDS, and we were on the CDC list, and kids were beating us up. I still remember that. I think of young people who are going through that now. To recap the answer to that question, it’s like you want to give them a hug, you want to tell them it’s going to be okay.

“Depi gen souf, gen espwa.” For as long as there’s breath, there’s hope.

I sensed from reading your work that it is in writing essays and books that you confront the answer and reality of this next question I’m about to ask. Faith, amongst other themes, is something you explore in your new book, “We’re Alone.” I think all of us have been in at least one situation where God “disappointed” us or didn’t come through the way we expected; when or where it seems like His promises are more paper promises than anything else. Everyday, our faith is tested by the contradiction of the reality that we see. How do you reconcile that? When God does not “save” us and what it means for your faith?

When my parents moved to the U.S., they left us with my aunt and uncle, and my uncle was a minister. So I grew up in the church basically. Both my parents were very religious. So I grew up with the idea that good should prevail. I think that’s something I still hold on to very tightly.

Both my parents had terminal illnesses, and so they had been told they were going to die, and had a really strong stretch of time where I saw how they wrestled with not wanting to die but knowing you want to die, and also being a person of faith dealing with that. I think that’s helped me become calmer in a way when the world rages around me.

I think the most powerful element of faith is knowing that we don’t control everything. That there are these greater, whatever specific religion you assign it to, forces at play, and that we are just like a speck in this whole massive, beautiful universe, and that sometimes we have to trust that things will be well. We have to act. The Bible says “faith without works” is dead. We have to act but you also have to believe in positive things in order to act and move towards them. And that’s what I learned from my uncle, who was a minister, and from my parents whose faith was the strongest I’d ever seen up close.

That sounds like the concept of “Even If” faith. Like, even if XYZ happens, my faith remains, which appears to be a broader, sturdier foundation of faith to rely on — faith based on who God is and not just what He can do.

Yeah. That’s the thing I learned from my parents. My mom, when she was told she was going to die, she would say, “Well, we all have to die.” And so it is how we’ve died, how we’ve used the time we have here [that matters]. I extend that to also having faith in other humans, and that goes along with the idea of not dehumanizing people. Having faith in their potential. If we bring it back to immigration, the people who come here, who risk everything, are putting their faith in something greater. They’re putting their faith into the future. What struck me in this election cycle is watching so many people who claim to be people of faith but are still able to call someone else an animal, or still able to just so easily discard that ‘love thy neighbor’ part of that faith.

It’s interesting that one can go through so much pain and yet still have a lot of faith in humanity. Hope is good, but at the same time, hope can feel like a very dangerous thing. The result of the election to me felt like even though it wasn’t surprising, it was still shocking. It’s fascinating that given all that has happened, even in your past, you are still able to have faith in humanity.

I go back to this Haitian proverb “Depi gen souf, gen espwa.” For as long as there’s breath, there’s hope. I’ve had to grab on to that. I mean, [laughs] what other choice do we have? We can’t just lay down and die. That’s what they want us to do.

In the final chapter of “We’re Alone,” you write that “Families, as my suddenly silenced uncle used to say, expand like ripples in a pond. Migration forces you to remake your family as well as yourself.” In what ways has migrating to New York City forced you to remake yourself?

When I came to the U.S. at 12, already sort of in this stage of formation, of becoming a young adult. I had grown up, from the time I was four, with my uncle and aunt in Port au Prince, and then coming to New York at age 12, just learning a new language, getting to know my parents again, getting to know my brothers, who were born in the U.S., it really was a reforming, or reimagining.

A couple of years ago, I did this interview that was turned into an essay. It’s called, All Immigrants are Artists, and in a way what we do as immigrants is similar to a work of art in which you get a blank canvas and you have to fill it in. You have to recreate a life. You have to recreate yourself. So for me, it was at the prime age of a pre-adolescent and then gradually [began to rebuild]. Of course, always in the immigrant experience, there are moments where you pause and you think what a parallel version of you would have been like if you had not migrated. I think everybody has that moment. It’s like where would you be now? What would you be doing? I would have had a very different life if I hadn’t come here, but the benefits of that life have always come at great sacrifice. I think that’s what we highlight less in the immigrant story that so much comes at great sacrifice, and we’re seeing more and more these sacrifices are greater for families who have to walk through the Darién Gap, travel through several countries, who take great risks for this opportunity. Of course I wouldn’t be speaking this language, and many other things. Immigration remakes us.

I saw this play the other night called “Bad Kreyòl” by Dominique Morisseau, who’s a Haitian-American playwright. One of the lines in the plays that one of the characters says: a person is “dyaspora,” that is, with the y, that’s how we say it in Haitian Kreyòl. And it says “blood here, home, elsewhere.” So this idea of of fluidity, and part of the ways that we are all remade, especially those of us who are Haitian or feel like we’re in the bull’s eye of this situation, we’re remade by our not-sudden but more-urgent precarity, hyper visibility, hyper vulnerability, because basically, a lot of people ended up voting in this election because they think we eat cats and dogs and are invaders. So that makes you certainly hyper vulnerable in this climate.

“What we do as immigrants is similar to a work of art in which you get a blank canvas and you have to fill it in. You have to recreate a life.”

At what point after moving to New York City at 12 years old did New York City begin to feel like home for you?

The height of anti-Haitian stigmatization was when I was in junior high school, 1981, when Haitians were on the CDC list, and that was terrible. We were beaten up all the time. We were called names and actually, my dad went to the principal at Clara Barton high school and said, ‘My daughter has to come to your school because she’s going to be a nurse.’ And they not only admitted me, it wasn’t my zone school, back then there were zone schools, but they put me in the Honors Program, which was like 30 nerds together, and we had all our classes together, and we were supposed to be on this path to become doctors.

When I started going to the Brooklyn Public Library a lot, when I started walking through the Botanic Gardens, when I started really feeling at home within my studies at Clara Barton high school, I think that’s when I started feeling like home. And, of course, reading books, speaking English better. In high school was when it started feeling like I was home. It also started feeling real, like I was here for a while, because my parents would always say, we’re going next year to visit Haiti, but we never went and I had a feeling where I was like, Okay, we’re gonna be here a good while.

Your first concrete childhood memory is of being “peeled off” your mother’s body on the day she left Haiti for the U.S. when you were four years old. What’s your second concrete childhood memory?

[Laughs] It’s funny because I get them in retrospect. I think that was my first memory because it just blocked off everything else. Then, I started thinking about other things that had predated it, like my mother taking me to school at three. But my other striking memory was of being beaten in my palm by my teachers [laughs] with a ruler. And then we had to do that thing where you are like [switching both palms].

[Laughs] I experienced that too. I imagine that some of the eight essays in “We’re Alone” took a while to weave together, given the weight of each subject matter. Which took you the longest to write?

I had written many versions of the closing essay, “Writing the Self and Others.” It’s one of the more personal essays, and there are very many different versions of it. Part of it is because it had that really full-circle emotional moment with my daughter at the airport. I was really freaked out by that when she was screaming for my mother at the airport, and it was like I was taken out of time.

It took me a very long time to figure out how to put all these things together, how to write about both my mother and my daughter together. That’s why I think the mechanism of the essay, exploring imagining the essay as a body of water, came into play. Once I had finished “Writing the Self and Others,” it really helped me go back and reframe the other essays.

In “Krik? Krak!,” in the epilogue, I say when you write, it’s like braiding your hair. I think of these essays in “We’re Alone” as being braided, but also as being fluid, like water. So the essay, “Writing the Self and Others,” took a long time in a way because it was a very emotional and personal essay, and it’s also something that I think launches my writing into the future because I hadn’t written so much about my children. It also is like, Oh there’s another generation here. Not only as babies — my daughter was in “Brother, I’m Dying” — but now as adults making their way in the world with this past that I have now left them, with all the things that I have written.

This interview has been edited for concision and clarity.

Do you know who should be in the next Our City? Email earlyarrival@documentedny.com.