On an overcast late summer day on a basketball court in Corona, Queens, the Capellanas del Desierto were struggling to find their footing.

“¡Tranquila! ¡Hagan juego!”

Cheers, cajoling, and guidance came from dozens of onlookers on the sidelines – the basketball players’ children, partners, and teammates, who had travelled from as far as New Jersey, Staten Island, and the Bronx, along with lawn chairs, snacks, drinks, and radios.

The Capellanas del Desierto – “female chaplains of the desert,” in Spanish – had mounted a valiant defense against Guerrero, the opposing team, but Guerrero’s shots kept landing. Capellanas player Heidy took a three pointer. It missed, and a Guerrero player sped down the court with the ball.

“¡Bonito eso!” came cheers from the sideline.

At the half, the Capellanas gathered in a circle around Roberta Tapia, their captain and the founder of this monthly women’s basketball tournament in Corona, Queens.

At 5 ‘3” and in her mid-40s, Tapia does not match the profile of a typical basketball player. She seems to be everywhere at once: advising her teammates, running down the court, checking in with the scorekeeper. Like the other Capellanas, Tapia wears a red and white jersey with a desert landscape that blends into the outline of a basketball. Tapia’s jersey has an additional element: the word “Pin,” short for Serafín, printed underneath the image.

What appears to be a neighborhood basketball game is actually an event meant to save lives. Thousands of miles away from the crowded courts and abundant homemade concessions, migrants are struggling to survive an arduous trek through the Sonoran Desert to find a new beginning in the United States. Many lose their way in the dizzying expanse of rocks and cacti. Tapia’s team funnels donations to volunteers who spend hours sifting through the desert, hoping to find them alive.

But often, it’s too late. Fighting extreme temperatures, precarious terrain, flash floods, and wild animals, hundreds of migrants lose their lives every year attempting the crossing.

Serafín López Méndez, Tapia’s nephew, was one of them.

The desert

Méndez had never traveled far from his rural hometown in the Mexican state of Guerrero, much less been to another country. But his heart was set on the United States.

Tapia remembers meeting him the last time she visited Mexico around 2007, when Méndez was a young boy. From the beginning, they had a special connection. Tapia’s father had recently been killed, and she felt isolated from her community. “Many people turned their backs to us, even my own family – and [Méndez] didn’t,” she recalled in Spanish. “He visited us, visited my mother and siblings, and he never left us alone.”

Like Tapia, Méndez played basketball. “He was a very friendly, humble boy, he had respect for everyone,” Tapia said. “He was so, so cheerful. He liked dances and the annual village festival. He always supported the community.”

As the years went by, Méndez grew impatient with the opportunities in his rural hometown. Tapia remembered a conversation she had with him shortly before he set out for the United States: “Tia,’” she recalls him saying, “‘I work hard here, but I want to make my own life. I want to have my own house, I want to help my parents more.’”

Tapia tried to dissuade him. “I told him, ‘hijo, it’s very dangerous. Just wait.’” But Méndez didn’t want to wait.

“He was anxious to come.”

In mid-April 2023, Méndez set out from his family farm. He was 24. The last time he spoke to Tapia was shortly before he crossed the border. He called her from Tijuana.

“He told me, ‘tia, I’m going over now,’” Tapia recalled. “‘I’ll see you again soon.’ That’s how he said it. And I said ‘yes, hijo. I’ll be waiting for you here.’”

Méndez’s family kept in close contact with him while he set out into the desert. But by the first days of May, he stopped answering his family’s increasingly frantic messages.

After several days, Méndez’s sister received a message from the coyote who had accompanied him. Méndez, the coyote told her, was exhausted. He couldn’t take the sweltering heat or the freezing nights. The group had left him behind near a highway, the coyote said, where the border patrol would pick him up.

“But that was all a lie,” Tapia bitterly recalled.

Tapia jumped into action when she heard the news of Méndez’s disappearance. Tapia was familiar with the desert, having crossed the Sonoran several times, first when she was 14 years old. She remembered the thirst, the endless walking, the coyote who abandoned her, and the sound of Border Patrol approaching as she hid with bated breath.

As soon as she heard her nephew was missing, Tapia started calling migrant rights organizations at the southern Arizona border, hoping one of them would help find him.

“I felt powerless because I didn’t know what to do. So I started to look for organizations that could go into the desert to look for my nephew.”

But, as her desperation grew, she found herself navigating an ecosystem of scams, threats, and faulty information.

“There are many organizations that just want money,” she said, in Spanish. “People would call me and tell me that they had him. And if I didn’t give them money, they would do something to him.” They asked for thousands of dollars – money Tapia didn’t have.

Finally, she rang the number listed for a search and rescue group based in Tucson. On the other end, a man with a deep baritone picked up. “Capellanes del Desierto,” he said.

The Capellanes

A chaplain and construction worker from Durango, Oscar Andrade is the leader of the Capellanes del Desierto, a Tucson-based volunteer search-and-rescue group composed of men and women from Mexico and Central America, many of whom have crossed the desert themselves or lost loved ones who attempted the journey.

The Capellanes frequently receive desperate calls from families whose loved ones have disappeared in the Sonoran Desert. When they get these calls, day or night, they spring into action, sending teams out to comb the uninhabited acres of shrubs, rock, and sand. They hope to find migrants alive, but more often, they only find remains. “Sadly, some people pass away minutes after we get there,” said Andrade. “We find them in agony.”

Officially, 8,000 people have died crossing the US-Mexico border since 1998. Advocates estimate the true number is three to ten times higher. Many blame the immense loss of life on the hardline “Prevention Through Deterrence” policy implemented in 1994, which aims to deter migrants from crossing the border by pushing them into the most hostile, dangerous terrain, making the journey as deadly as possible. As a result, migrants often get hopelessly lost in the desert and die alone.

As Tapia and her relatives rehashed the coyotes’ directions on the phone, Andrade wasted no time in donning a neon high-vis vest, loading his battered white pickup, and speeding towards Méndez’s approximate location. Andrade and the group of Capellanes located the rock with an arrow that, according to Méndez’s coyote, pointed to his location.

But after six hours picking through miles of desert, the Capellanes found no sign of Méndez. There was nothing to do but go home and try again the next day.

As the days and weeks passed, Tapia and her family members felt a growing sense of dread.

It took months of grueling expeditions before the Capellanes found a sign of Méndez. On a cold morning in September 2023, miles from where the coyote said he had disappeared, they saw something white — a femur.

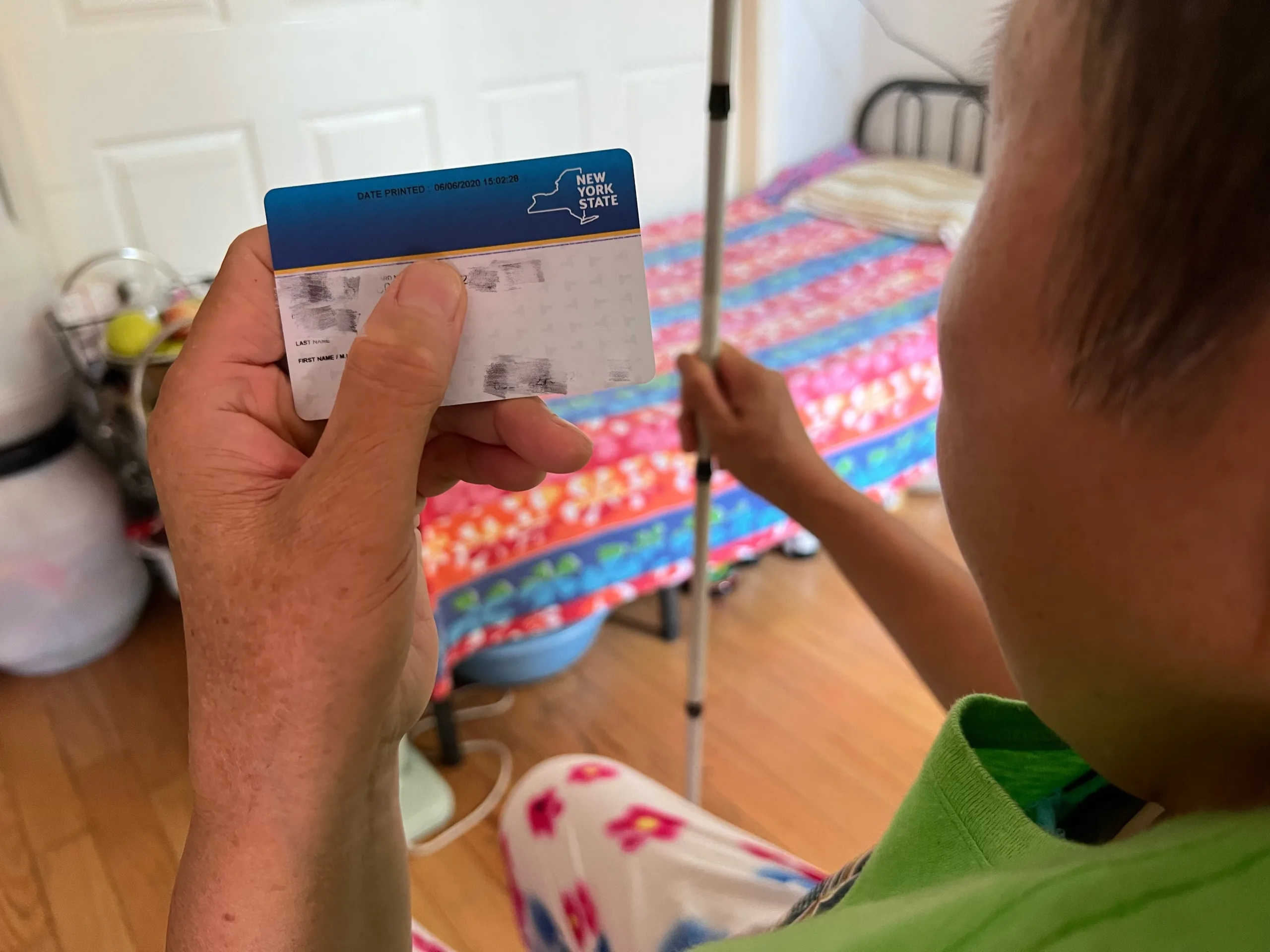

Then, nearby, an arm bone, a skull, and a wallet with Méndez’s driver’s license, ID, and a few wallet-sized photos of Catholic saints. Andrade texted Tapia right away. He wasn’t sure if the bones were Méndez’s, much less if the cause of death was dehydration, an animal attack, or a bullet from a coyote.

Méndez’s family, like many of the families Andrade works with, asked for a photo. When he gets these requests, Andrade tries to dissuade them. It’s better, he thinks, for families to remember their loved ones full of life; in many cases, a photo would show nothing but bones. “Imagine him when he was with you,” Andrade told Méndez’s family.

Tapia and her family ordered a DNA test from the Mexican consulate, which requires a match before it sends remains back to families. But the cost of the test, which can be upwards of $1,500 for bones, precludes some families from getting their loved ones’ remains returned.

For Tapia’s family, the DNA test came back a positive match. A year later, Tapia still can’t quite grasp the loss of Méndez. “I continue to hope that I can find my nephew alive,” she said.

Andrade and Tapia kept in touch even after Méndez’s remains were sent back to Mexico, she in Queens and he in Tucson. Tapia forwarded Andrade videos of her nephew’s funeral in his hometown in Guerrero, where neighbors gathered to honor his short life.

Months later, Andrade received a surprise call from Tapia. A longtime basketball player, Tapia told him that she was renaming her women’s basketball team in honor of Andrade’s work. Her team would play as the “Capellanas del Desierto” – the feminized form of “Capellanes” – to support the group’s mission of rescuing migrants in the desert.Tapia’s team, a crew of mothers and grandmothers, planned to host tournaments around the Tri-state area to raise money for them.

“It left us speechless,” Andrade said. It was hard to believe that there was a team, thousands of miles away, that carried their name. The Capellanes have a framed photo of Tapia and her teammates in their Tucson office. Whenever visitors ask about it, Andrade proudly says, “In New York, there’s a basketball team that has our name. They’re not very tall, but I was like…wow!”

The Capellanas take the court

Since then, most months, the teams — with names like Guerrero, Fénix, Jersey City, West Side 99, Queens, and Mercenarias — come with their families for a day-long tournament.

Over the sounds of cumbia and norteño and the smell of warm tostadas de tinga, which Tapia sells on the sidelines, the players fight for the ball.

Many of them have traversed the Sonoran desert themselves. Eulogia, a player for the Queens team originally from Puebla, Mexico, remembered crossing with her family from Nogales 17 years ago. “Many people get lost because they walk for such a long time,” she said in Spanish.

Eulogia brought her daughter, just four years old at the time, with her. “It’s more dangerous because you’re bringing children with you. But the education here is better,” she said. Eulogia’s daughter is now 21 years old and in school in New York City.

Eulogia works hard to afford New York City rent; her husband holds two jobs. The basketball tournament, she says, brings a welcome respite. When her brother visits from Mexico on a tourist visa, she reminds him to give her mother, who is still in Puebla, a hug for her. “I can’t hug her, so I say, ‘you hug her for me,’ ” she said.

The teams’ entry fees and donations collected throughout the tournament are set aside for the Capellanes and other causes close to Tapia’s heart. In September, she sent money to victims of Hurricane John, which had devastated the Mexican state of Guerrero, where she and many of her teammates are from. In November, the tournament raised money for Creando Algo Especial, a local organization for children with autism; Tapia’s son is autistic.

In the early days of the tournaments, some of the players’ husbands — including Pablo, Tapia’s husband — doubted their spouses’ zeal for basketball. Pablo thought his wife was better suited for housework.

But, however begrudgingly, the men have become the Capellanas’ biggest fans. Some, like Pablo, moonlight as referees and coaches. Others are vocal cheerleaders. During a particularly rainy tournament, the husbands of the Capellanas players scurried onto the court between games to sweep away the accumulating water.

Many admire their partners’ strength, both on and off the court. “She may be short in height,” said Pablo, watching his wife play, “but she is unstoppable.”

“For us, it’s a lot.”

Other teams often ask about the meaning of the teams’ name and the art on their jerseys, and Tapia tries to spread the word about the Capellanes’ mission.

“I tell them, ‘thank you for supporting the Capellanes del Desierto, so they can continue to look for more migrants,” said Tapia. “No longer for my nephew, because they found him. But there are people who have been missing in the desert for years, and their families don’t even have a trace of them.”

The Capellanes never ask for money from families who call them for help. Even when families ask if they can donate, Andrade, who knows many live in difficult circumstances, asks for their prayers instead. The group uses their own salaries — and now funds from the Capellanas’ tournaments – to fuel their days and nights searching the Sonoran.

Andrade estimates each search costs the group around $500, factoring in water, snacks, gasoline for at least three cars, and oxygen tanks and medical supplies for people they find alive.

Over the past year, Tapia has raised several hundred dollars for the Capellanes. Each team pays $200 to participate in the tournament. At the start of each tournament, team captains determine how to distribute the money. A portion goes to the top three winning teams; some goes to the scorekeeper as compensation; and the rest, usually several hundred dollars, is donated.

“Some people might say it’s not that much,” said Andrade, “but for us, it’s a lot.”

Andrade and Tapia have become close friends, even though they’ve never met in person. She calls him “hermano,” or brother, and the Capellanes always refer to her as their little sister.

Andrade hopes to visit New York next year to cheer on the Capellanas as they take the court. He doesn’t plan to join in – “the ball always escaped me,” he laughed.

But Tapia is eager to join Andrade during a Capellanes search-and-rescue mission on the same land she crossed as a teenager, seeking a new beginning in the United States. Four decades later, she is expecting her green card any day. Tapia plans to travel back to the border and help the Capellanes find those who, like Méndez, once entered the Sonoran full of hope.

“When my papers arrive,” she said, “I will go walk in the desert with them.”