‘You have mail,’ a detention officer will announce at an ICE facility in Buffalo, New York this December, addressing the recipient by their name.

While immigrants in detention can receive and send letters to/from their families, this would not be a message from a family member or a loved one. This would be a handwritten letter from strangers who volunteered to write to people in ICE detention.

To hear their name be called in an environment where they are usually addressed by their alien number or jail identification number, would hopefully bring joy and comfort in what is likely to be an isolating holiday season.

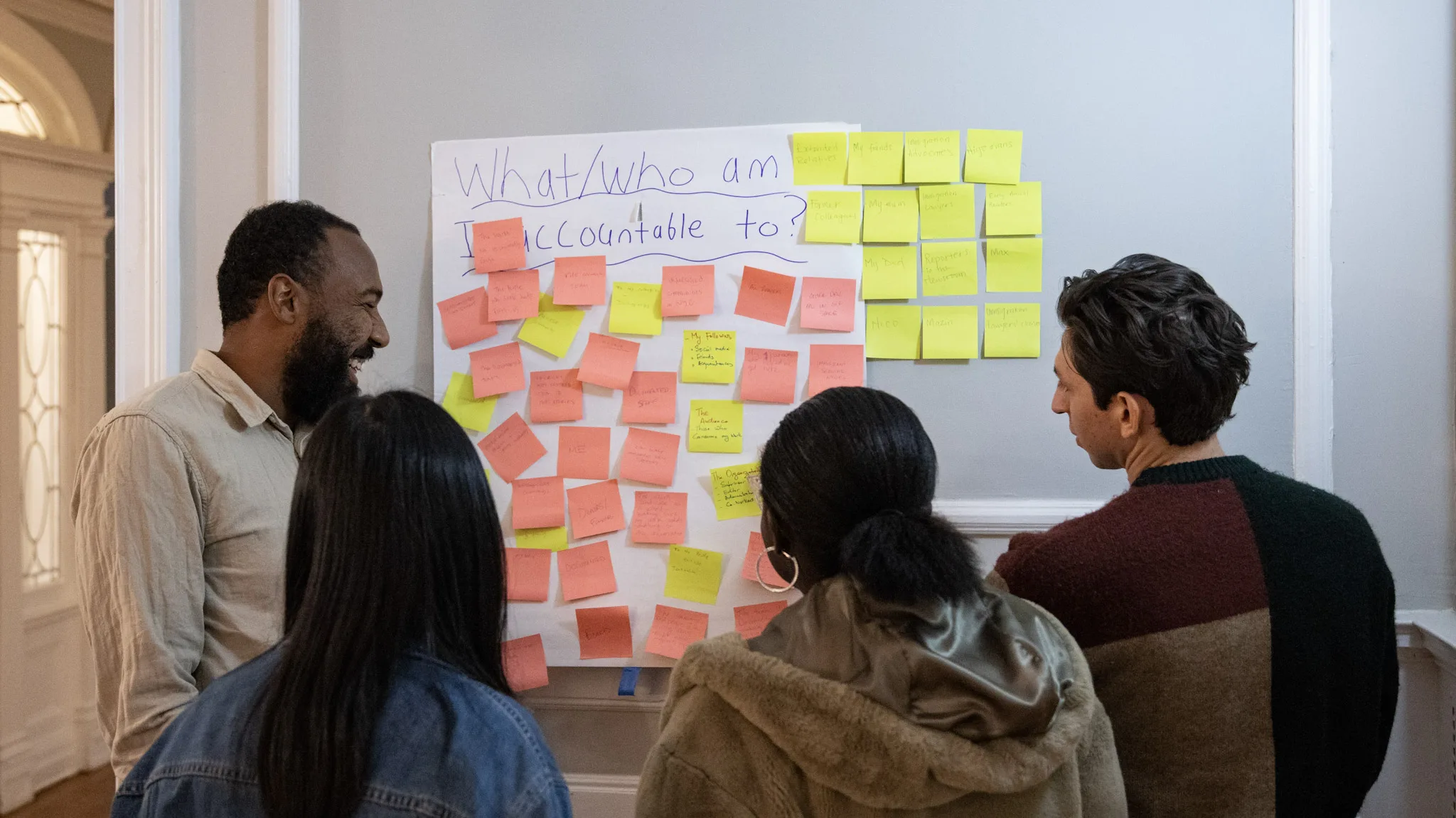

“It’s interesting to write a letter to somebody that you don’t know, and only having, really, their name to go off of,” Tamerra Griffin, tells me at a recent letter writing event organized by the Dignity Not Detention campaign and Critical Resistance.

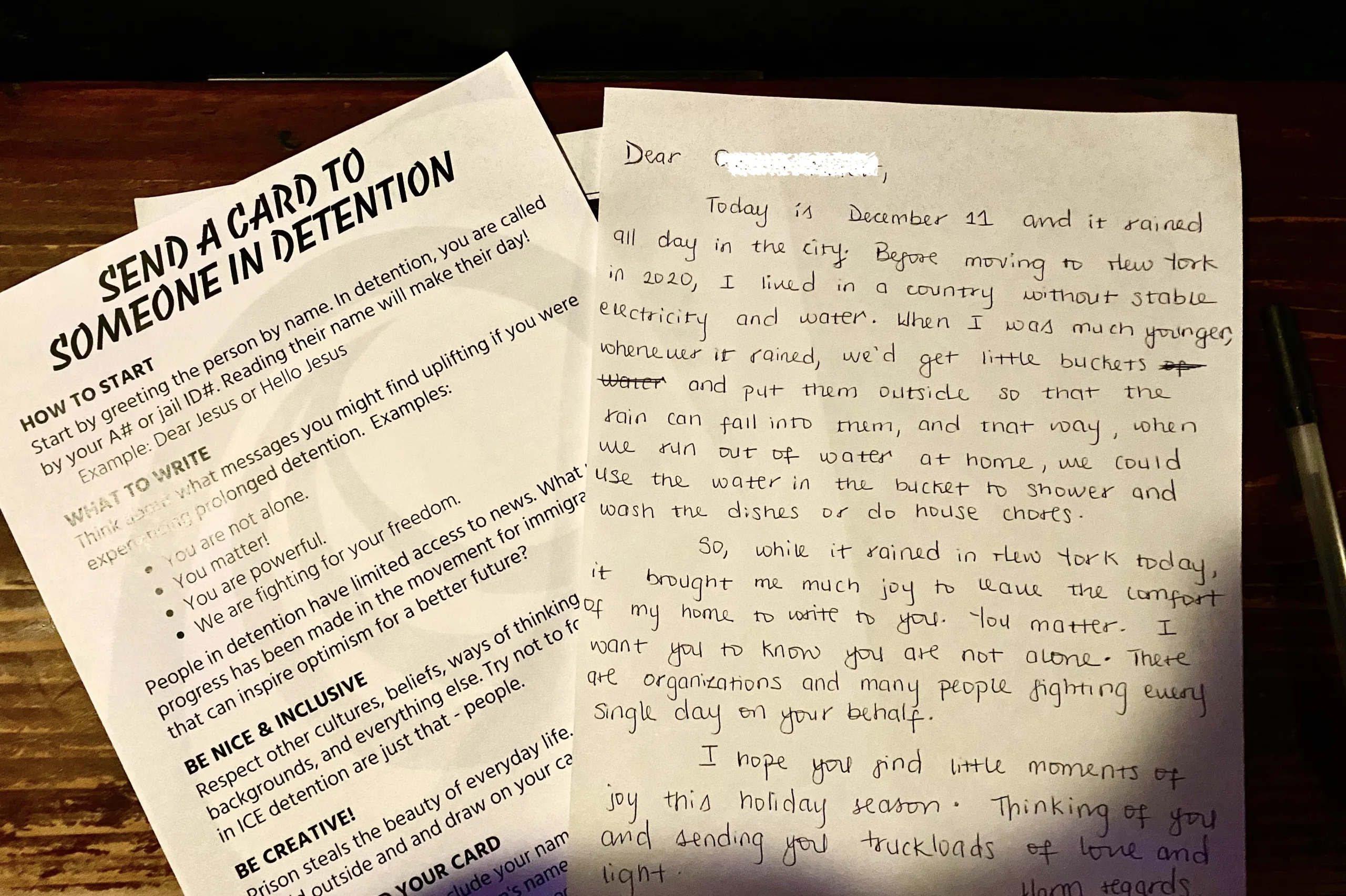

Griffin is one of 14 volunteers who have arrived at C’mon Everybody, a live music venue in Brooklyn, to write handwritten letters to immigrant detainees. Organizers have given each person a pen, a sheet of paper, the name of a detainee they can write to, and ideas on how to start: “Be nice and inclusive.” “Be creative.” “Prison steals the beauty of everyday life; share details about the outside world.”

Griffin decides to give her assigned detainee an update on soccer — not because she knows if her detainee loves soccer, but because she herself writes about women’s soccer.

“I told him which teams are doing well, which teams are struggling. Liverpool, for example, is having a very successful season. Nobody really expected this team to be doing so well this season,” she says. “I tried to connect that to why we’re doing this, which is that people can achieve anything if they unite around a common belief and everyone really pours into that belief.”

At the bottom of the letter, Griffin drew a beach. “That’s something that brings me peace when I need motivation, inspiration, a sense of hope.”

Griffin and the other volunteers’ letters will reach just a handful of people in ICE detention, which, according to data current as of December 1, 2024, is about 40,000 people. Of those being held by ICE, about 61% have no criminal record and many others have only minor offenses, including traffic violations. In New York State specifically, there are over 600 immigrant detainees held at detention centers in Batavia, Plattsburgh, and Goshen.

Griffin had no idea she was heading to an event to write letters to immigrant detainees. The night, for her, was a surprise date. “It’s a great surprise. I love any time art and activism combine. Things like this feel like little acts of resistance, all put together into one event which I think is so cool and important.”

In the room, Viju Mathew, the organizer of the letter writing event from Critical Resistance, stands on a stage to face the volunteers: “What we’re doing today is pushing forward our prisoner solidarity work, and we’re letting people know that we are here in the struggle with them. We are here to support them,” he says. “The letter writing is more specifically under an area of work called ‘inside outside.’ It’s basically breaking the isolation that walls or cages create, specifically migrant detention.”

Mathew says it is also an avenue to keep detainees updated about any news on the campaign to pass the Dignity Not Detention Act into law. If passed, the law would end contracts between the ICE and county jails in New York.

The idea to write letters to immigrants came about after members of the Dignity Not Detention coalition asked individuals released from detention what helped them maintain hope while in detention. Their responses consistently highlighted a few key factors: staying connected with family through phone calls, having commissary funds to purchase food due to the poor quality of detention meals, and receiving letters.

“When they used to hear the officer call their name, for example, ‘Rosa, you have mail.’ It was something different, and it made their day,” said Rosa Santana, the bond director and interim co-executive director of Envision Freedom Fund.

Since December 2021, Envision Freedom Fund — an immigration bond fund that has freed 1,000 people from detention since 2018 — has coordinated with volunteers to send handwritten letters to immigrants in detention. Usually, they plan to send the letters around holiday seasons. Last month, community members and volunteers wrote letters for Dia De Los Muertos (Day of the Dead) to remember those who have died inside detention and jails in New York City, and to connect with people inside.

Some of the letter writing organized by Envision Freedom Fund is written by people who have gotten out of immigration detention through the help of immigration bonds and are awaiting their court hearing. The national average payment for an immigration bond set by immigration judges is $7,000 — an amount that is unaffordable for many families and friends of people in detention.

Having “paid their bonds, we take this opportunity for people who have been inside detention to write letters too, because they know what a letter means,” Santana says.

Many of their letters are written in Spanish, as 90% of Envision’s community members are from Central and South America, Santana says. They also write letters in French and English too. People are paired to write to detainees depending on the language the recipient speaks. Often, Santana’s organization will send the handwritten letters along with commissary funds so that the detainee can purchase food and other resources including stamps to write back. This year, only letters were sent, as the organization experienced limited funds. There is no expectation for recipients to respond to the letters, Santana says.

Beyond single volunteer events, there are longer-term programs too. “People’s engagement can be one-time but we hope it’s more than that. The pen-pal program has been ongoing since the work started a few years ago,” Mathew says.

However, there are obstacles to maintaining correspondence, too; immigrant detainees have to pay for postage, mail gets lost, ICE moves the detainee to a different facility or they might no longer be in custody. Other instances come with “no explanation at all,” Santana tells me, “and the people were there and the address and the A- numbers and names were correct. We just had to resend them.”

Yet, writing letters is still worth the effort, she says. More often than not, the handwritten letters do get delivered within three days to a week. In many instances, immigrant detainees write back too. “The response, I would tell you, they’re very grateful,” Santana says, as she prepares to read out one of such letters to me:

“It is comforting and gratifying to know that I am not alone in my struggle against unjust prolonged detention,” notes the letter, which is from an immigrant detainee at the Buffalo Service Processing Center in Batavia, New York. The letter goes into detail about harsh conditions at the detention centers: 16 hours of being locked in a tiny cell, limited access to the law library. At the end, the letter says, “I’m very deep in gratitude to all. Trust and hope.”

While these letters may seem like small gestures of kindness, Rosa Cohen-Cruz Esq., an attorney who works as the Immigration Policy Director at The Bronx Defenders says these letters actually help detainees in fighting their immigration cases.

Immigrants in detention are “the ones who have to choose to continue to keep fighting, and then they work with us as legal services and as lawyers to support them in that,” Cohen-Cruz says. “But it’s those personal connections, those letters, that helps sustain people through [their pending cases], that will ultimately be what helps people have the strength to kind of endure what it takes to fully fight their cases.”

Sometimes, detainees also write back highlighting how much a written letter helped with their mental health. Santana notes there are some “responses from people who have said, ‘I was in a very dark place,’ you know, it’s very hard for people to be in detention.

“Sometimes it means that they’re going back to face certain death or torture, or they know that they’re going to be permanently separated from their children,” Cohen-Cruz says. It underscores the devastating toll detention takes on a person’s mental, emotional, and physical well-being, leaving them feeling too broken to continue fighting, she says.

One of the volunteers, Gracie, who only wanted to be identified by her first name, tells Documented she has been a volunteer letter writer with Critical Resistance since 2021. She drew some stars in her letter and wrote some words of encouragement to the immigrant detainee she was matched with. “I hope that the letter can provide some comfort to him, reassuring them that they’re not forgotten and that no matter how much it might feel like they’re alone, there are people on the outside doing all we can for them,” she says.