On my first day working at the shelter, I had just received my ID badge and was about to meet my team, but all eyes were on two supervisors arguing in the center of the room. One tried to end the conversation by leaving, but the other followed her to continue the argument. Their voices were reaching a crescendo when all of a sudden someone interrupted to announce that a shelter resident’s water broke and an ambulance was on the way. All of this happened before 8 a.m., before any formal introductions, and less than 10 minutes into a 12-hour shift.

As an operational site lead, I managed teams of caseworkers across multiple shelters. Caseworkers meet with asylum seekers staying at the facility, whom we referred to as guests, and conduct regular meetings throughout their 30-60 day stays to help them figure out next steps. The shelters are meant to be transitional emergency housing, so our goal is to help guests make a plan to obtain stable, permanent housing by directing them to legal, medical, and social services as needed.

Also Read: How Migrants Can Access Shelter in NYC as “New Arrivals”

Before I started, I couldn’t picture what the actual shelters would look like. The magnitude of the situation — of tens of thousands arriving in New York — only heightened the strangeness of seeing social services unfold in once-grand hotel lobbies beneath historic chandeliers. However, the majority of the shelters I eventually saw looked very temporary, which was somehow even more jarring. Picture an empty open office covered in a grid of metal cots. Barren warehouse floors filled with small, windowless rooms with no ceilings. Makeshift canteens with table seating facing forward like a classroom.

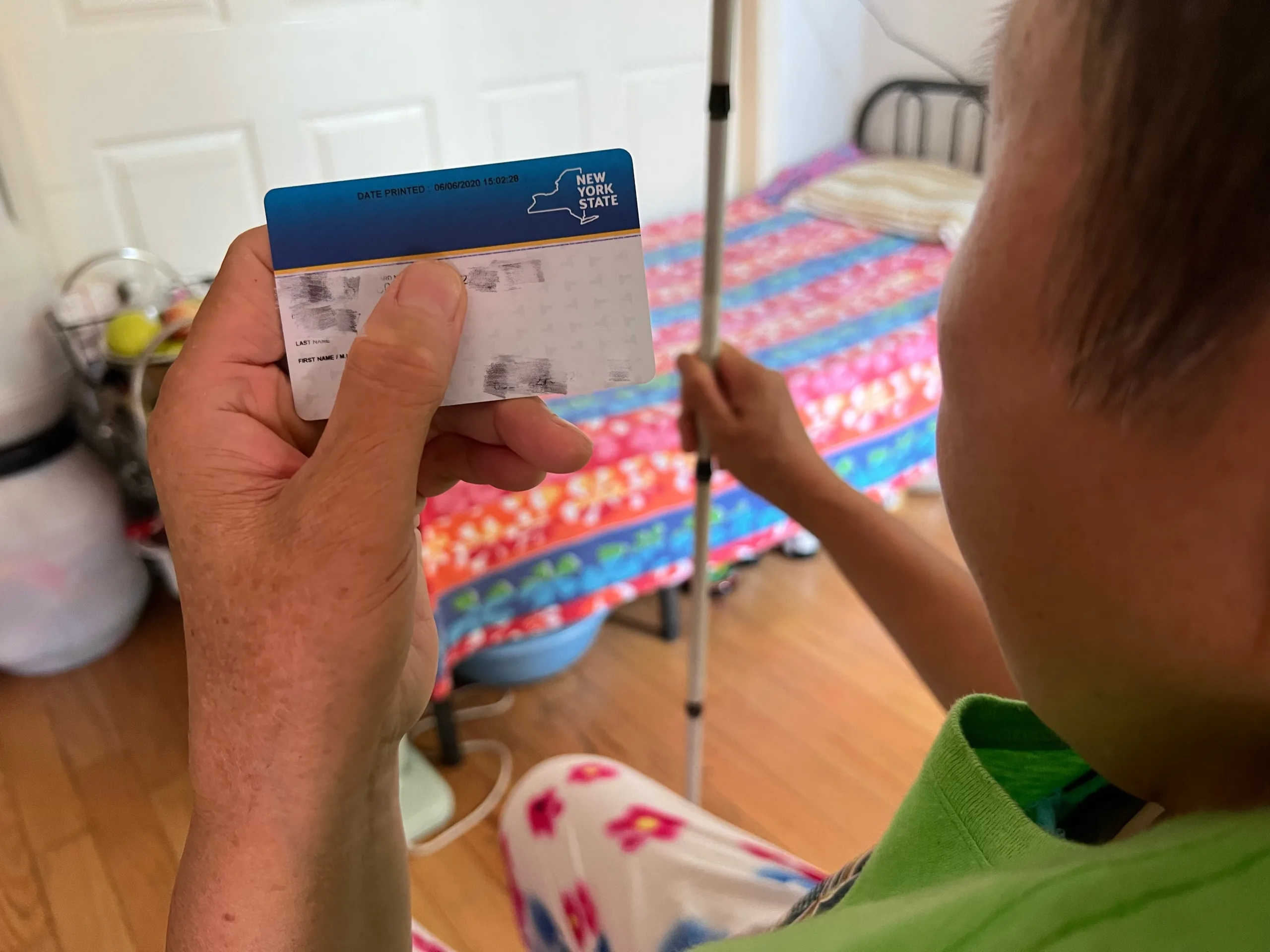

For an unpredictable space, there was a routine rhythm to each day. In the mornings, families amassed in the exit area to scan their shelter identification badges and leave for school or work. An evening rush of guests queued to “badge in” at the start of dinner hours. During Ramadan, the Muslim holy month, the men’s shelter emptied as guests put on their best and headed to a local mosque. The men started leaving well before sunset, because the wait times for the elevator of the high-story shelter could be upwards of 40 minutes and they didn’t want to be late for evening prayer and the breaking of their fasts.

A bulk of my casework focused on banal requests like tracking down lost packages. The task is ordinary, but failure is consequential. When I couldn’t locate a guest’s undelivered package, all of his original transcripts and diplomas from Iran might as well have been destroyed. Regrettably, his stay at the shelter ended without any resolution, and to my knowledge, his mail never materialized. A missed letter from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services could lead to a missed biometrics appointment, which would be enough to make a judge stop your Employment Authorization Document clock before it reaches the minimum 150 days wait required to apply for work authorization after you’ve filed your asylum application. This creates a conundrum — to unpause your EAD clock, a lawyer can help write a letter on your behalf, but how is one supposed to afford a lawyer if one cannot work?

The shelters are still not connected through a centralized mail system, so delayed deliveries are a regular predicament. The consequence for missing a court appearance is grave, and often leads to schedule for removal proceedings, i.e. deportation, even if the absence was due to an ill-timed hospital stay or a miscommunication at the courthouse.

Also Read: Here Are The Benefits Asylum Seekers Actually Get In New York City

Sometimes I felt conflicted between following shelter procedures and doing what I thought was right. One afternoon a man came back from an 11-day hospital stay after having open heart surgery. He wanted to move from a cot on a congregate floor to a private room at another location so he could heal in a calmer, cleaner environment. I checked his medical paperwork and planned to send his transfer request later that evening. I told him he would likely receive an answer in two weeks, which is the standard wait time, but he demanded to transfer locations the same night.

He was adamant, so I offered to send a follow up email, but he persisted. His resolve pushed me to keep searching for someone who could expedite the request. Later that evening, after hours of back and forth phone calls and approvals, I carried his bags to an Uber and helped him move into a private room at a different shelter. We sat quietly in a hallway waiting for his room key, and he broke the silence to tell me he was really grateful. I replied that it was my job and that he was right, he should have been moved to a private room from the start.

I left the shelter system right before the election, and as I reflect on my time there, I remember the little victories: caseworkers who reunited families in the middle of the night, staff who pooled their own money to buy socks for people who arrived in sandals during the winter, and the guests who came into the system without knowing English and now communicate without the help of translators. The best caseworkers didn’t have all of the answers, but were willing to engage in the tedium of navigating bureaucratic systems.

One of the most poignant moments came when a man learned of his mother’s sudden passing. Bereft, he decided to fly home, abandoning his asylum journey. In response, guests and staff collected money for him to ensure he didn’t fly back empty-handed. For many asylum seekers, there wasn’t one singular act of kindness that made a lasting difference, but rather consistent support that led to meaningful progress. For months, another case worker and I followed up with a deaf guest to ensure that he saw an auditory specialist. Before I left, he had been fitted for a cochlear implant and for the first time since he was a kid, he was learning to hear again.

But even with medical miracles and incremental progress, there are no guarantees that people will transition from survival to stability through self-sufficiency. Many asylum seekers find jobs but are struggling to save money since repaying their debts and caring for their families oceans away take priority. Others leave the shelters with the hope of finding work out of state. Yet for the vast majority their only plan is to return to the arrival center for new housing placement.

Also Read: Asylum Seekers to Trump: “Why Do You Hate Immigrants So Much?”

As shelter systems across the country contract, thousands of people are being pushed to make increasingly difficult choices. One older gentleman confided that the indignity of not working, of not being able to even buy himself a cup of coffee, drove him to consider abandoning his asylum claim and returning to his country to die alone. Hearing this as a service provider made me feel like I had failed him. When the systems designed to protect and help are cracking, do individual actions carry more weight? I’m holding out for an answer because of an idealistic hope that migration on such a global scale could create something meaningful. It’s a concern that lingers, leaving me — and so many others in this uncertain time — grappling with complex questions and no simple answers.