In 1986, Pei Mei’s family of eight immigrated from China to a rent-stabilized one-bedroom in Chinatown. With a family consisting of Mei’s grandparents, parents, brother and her aunt’s family, Mei’s father divided the bedroom and living room of the tenement apartment into multiple sleeping areas.

The apartment soon became the family’s income point. More of Mei’s relatives immigrated to New York and her family would house the new arrivals for months until they found work and moved into their own spaces.

“Everybody all crashed into that little apartment to stay there with me, so, at one point at the dining table, we had between 12 to 16 people at every meal,” recalled Mei. “It was like a full house, basically. Everybody, everybody has stayed in my apartment for a period of time.”

Having lived in Chinatown for most of her life, Mei remembers her neighborhood as one bustling with families and young children like hers. But over the years, most of these residents have moved out of the community, leaving only elderly neighbors who live in units more cramped than hers.

Also Read: The Last Wedding Shop in Chinatown

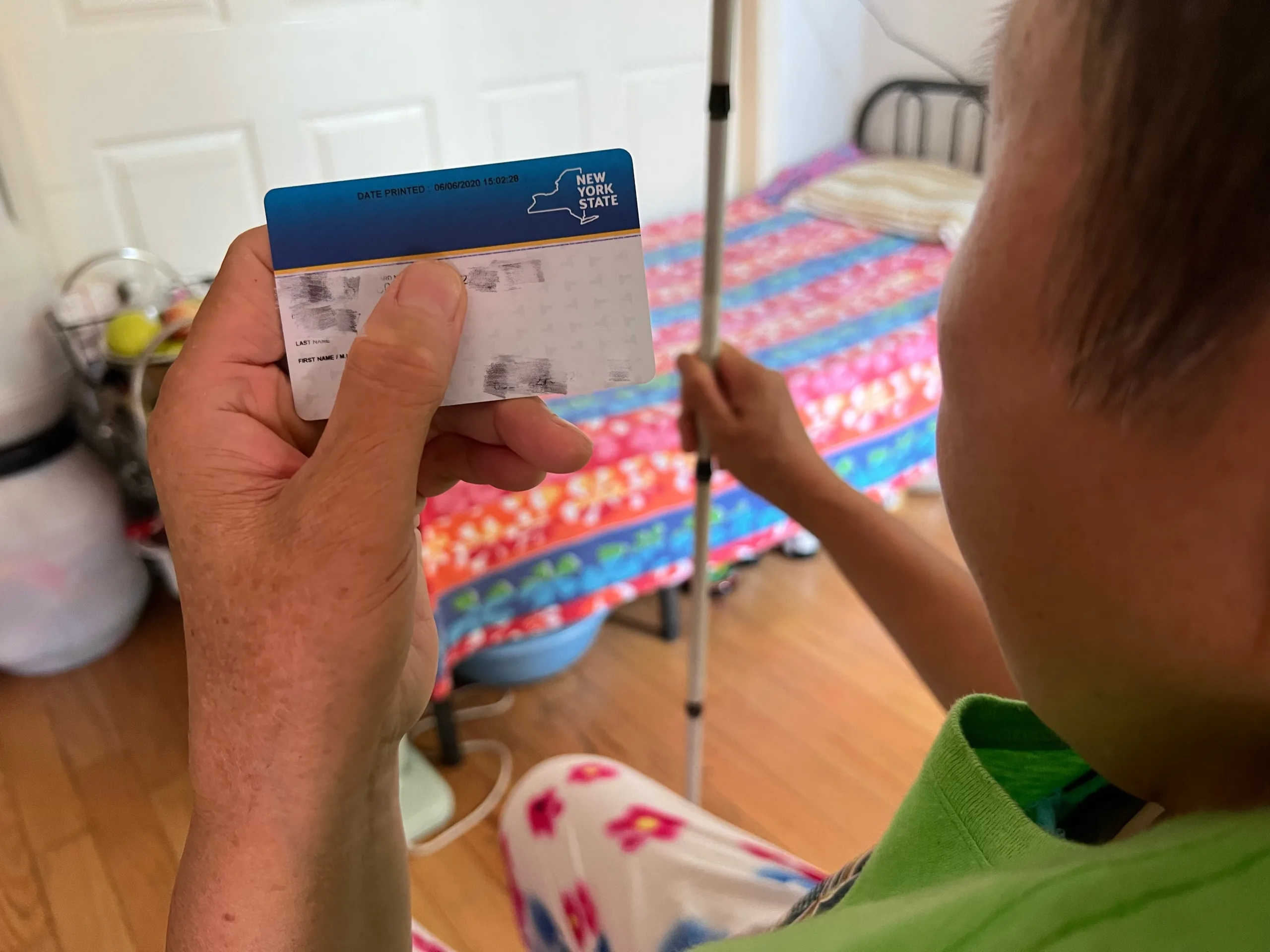

Mei, who inherited the lease after her father’s passing, still lives in the apartment with her two college-aged children, both of whom call Chinatown their home. But today across Chinatown, she sees that most of the rent-regulated tenement housing stock is occupied by aging tenants.

According to experts, this phenomenon is indicative of the greater decline of Manhattan’s Chinatown, as high populations of elderly tenants in affordable housing units deters economic growth by discouraging young people from investing in the community.

With the quality of housing declining in Chinatown, younger residents are choosing to move to suburbs and affluent districts to buy property, depleting the area of potential business activity. Despite most of her relatives leaving Chinatown, Mei remains rooted to the community, being a resident for nearly 40 years

In an effort to revitalize the area, advocates are championing an alternative model: Community Land Trusts.

Community Land Trusts (CLT) are a form of property ownership where a nonprofit governed by a community board, purchases and manages a designated area of land. The model is designed to ensure that any property sitting on trust land is perpetually affordable.

Once a nonprofit acquires a property into a Community Land Trust, members of the community board can purchase units which are capped at an affordable range. An adult who either lives in the property managed by the Community Land Trust or resides close enough to be considered part of the area’s “community,” can become voting members of the board. A Community Land Trust’s community board is made up of such residents, public officials, local funders, nonprofit housing providers and other public representatives. As voting members of the board, residents become responsible for a property’s maintenance in addition to any future re-sales of units which will continue to be sold at an affordable price.

According to legacy landlords like Jan Lee, co-founder of Neighbors United Below Canal, nearly 75% of all housing in Chinatown is rent-regulated or below market range. This number is highest among tenement buildings, whose operating costs are typically shouldered by ground floor commercial spaces, leading to higher commercial rents, according to advocates. As high costs to landlords spur even higher commercial rents that deter new businesses, Chinatown is faced with a shrinking, aging population with few young residents.

“What you have is an aging population, no turnover,” said Lee. “You have people aging in their apartment for 50 years, and the apartment becomes decrepit. It’s no longer meeting its building code, and when it becomes vacant, what do you think are the chances of that landlord renting that apartment for $65 a month? That doesn’t make a community stable.”

This instability is felt by long-time residents like Mei, whose neighborhood is now mostly populated with pharmacies and elderly customers. In an effort to reverse Chinatown’s aging decline, advocates argue that adopting Community Land Trusts offer a potential solution to create permanent affordable housing stock that benefits both future tenants and landlords.

Touted as a progressive model for increasing affordable housing, Community Land Trusts have been implemented by landowners in Boston’s declining Chinatown and have grown in popularity in New York through advocacy efforts by the NYC Community Land Trust Initiative with support from the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development. In New York, Community Land Trusts are often referred to as nonprofit Housing Development Fund Corporation cooperatives, which are entitled to reduced real estate taxes and stricter income and resale restrictions. Cooper Square is one of the city’s oldest active examples.

Since 2018, advocates with the Chinatown Community Land Trust initiative, have worked to popularize the notion of such trusts to prospective sellers and landlords.

Wellington Z. Chen, executive director of the Chinatown Partnership Local Development Corporation and former commissioner of the NYC Board of Standards and Appeals, has long advocated for the implementation of Community Land Trusts. Chen says that by adopting Community Land Trusts, nonprofit landlords benefit from reduced property taxes, which could save them upwards of $100,000 a year and leave buildings better maintained as rent-stabilized tenants improve their quality of living.

“In lieu of taxes you use that money to replace roofing, repair the boiler, and emergency lighting. We work so hard to preserve the mom and pop shops, because they are helping to support these tenement buildings and affordable units upstairs,” said Chen.

Also Read: Chinese Tenants Are Stranded at NYC Housing Court Without Language Support

According to Mei, most landlords are unmotivated to initiate repairs, leading tenants to hire out their own contractors which can be costly. As such, releasing some of the operating pressure on such aging, legacy structures can help landlords make necessary repairs.

So far, only 15% of Chinatown’s community are homeowners, with the vast majority being rented at below market rate. According to Jacky Tik Wong, a coordinator of the Chinatown Community Land Trust initiative, having few opportunities for home ownership deters communities from investing and protecting cultural landmarks. Through Community Land Trusts, nonprofits can delegate property ownership to residents who will have more incentive to revitalize the community and protect the interests of low-income renters.

“We stabilize the community people because people would have a real stake in the neighborhood,” said Wong. “This is a tool that they can build equity over time. They will stay in this community for a long, long time. So when the community has a problem, they will fight for the community.”

By increasing purchasable affordable housing stock, land trusts can help lure younger residents and culturally-specific businesses. As New York State strengthens tenant protections for rent-stabilized leases, Wong states that landlords may be less inclined to leave units empty to flip into more expensive leases, creating openings for land trusts.

“We are competing against [Chinatowns in] Brooklyn. We are competing against Flushing, Queens. We need to be able to retain people,” said Wong. “The reason why they are not staying in our community is the lack of quality housing. They are not able to build equity in this neighborhood.”

According to advocates, most tenements in Chinatown are ill-maintained and are at significant risk of fires among other dilapidating conditions. An analysis from 2023 found that the area is one of the biggest fire hazard hotspots in lower Manhattan.

Currently, Wong and his team are looking to purchase aging properties at auction to convert into Community Land Trusts. In doing so, he hopes that these efforts will slow the displacement of ethnic communities as Chinatowns nationwide have shown steep trends of decline. Landlord Lee observed that most of Chinatown’s “contextual businesses” which ensure the self-sufficiency of the neighborhood have slowly disappeared, indicating the gradual decline of the community at large.

“The beauty of New York is that a lot of the neighborhoods that are ethnic enclaves are actually owned by the people who live there, who will rent to contextual businesses,” said Lee. “So when we leave our greatest ethnic neighborhoods, that’s when you lose the soul of the community.”

Prior to events organized by Wellington and Wong, residents like Mei, were unaware of Community Land Trusts. Mei, whose one-bedroom apartment has been the heart of her family’s legacy in New York, is now more open to the possibility of owning the unit in hopes of preserving the space for generations to come.

“This is more of a family home where everybody has a memory,” Mei said. “So that is something that I would like to keep, and for everybody to have a place to come home to.”