More than a thousand New Yorkers have been arrested protesting government and institutional political and material support for Israel’s destruction of Gaza since the October 7 attacks. An executive order quietly signed by President Donald Trump may now enable the government to deport any immigrants who were arrested, and criminalize others, according to legal experts.

President Trump issued his executive order, called “Protecting the United States from foreign terrorists and other national security and public safety threats,” on his first day in office. The new order is said to be an evolution of the ‘Muslim ban’ he issued after first becoming President in 2020, which originally banned people from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the United States.

The latest iteration of the ban focuses on both non-Americans applying to come to the U.S., and those legally here, with the order dictating that non-citizens must not “bear hostile attitudes” toward “citizens, culture, government, institutions, or founding principles” and “not advocate for, aid, or support designated foreign terrorists.”

It demands a list of actions within the month “to protect” Americans from the “actions of foreign nationals who have undermined or seek to undermine the fundamental constitutional rights of the American people, including, but not limited to, our Citizens’ rights to freedom of speech and the free exercise of religion protected by the First Amendment.”

It also seeks to protect against foreign nationals “who preach or call for sectarian violence, the overthrow or replacement of the culture on which our constitutional Republic stands, or who provide aid, advocacy, or support for foreign terrorists.”

Also Read: Muslim Families Continue to Struggle Due to Travel Ban

The language of the executive order does not specify what actions or what rights non-citizens have to undermine to be considered culpable. Justin Harrison, an expert on protests and first amendment rights at New York Civil Liberties Union — the New York chapter of ACLU — said he believed the language was intended to be vague. “The broad ambiguity of the language is designed to give the administration as much wiggle room as possible,” he said. However, he noted that people targeted could face criminal charges or have their visas and green cards pulled. “It’s a call for viewpoint discrimination. It’s a call for discrimination by subject matter. It can be used to persecute not only political protesters but people who speak out against Trump’s priorities.”

Harrison believes there is “a lot of unconstitutional meat in this proposal.” He said that the order violated First Amendment rights, noting that the First Amendment grants protections regardless if you are an American citizen or not.

“Preaching sectarian violence can be protected by the First Amendment,” he said. “[And] Advocating for foreign terrorists can certainly be protected speech again as long as it doesn’t fall within one of the exceptions to protected speech, such as speech that’s likely to produce an imminent violent result.”

Harrison added the administration could enforce the order by “prosecuting people with a crime, subpoenaing their records, invading their privacy, searching them, tracking them, or lining them up for deportation or exclusion somehow,” and that all these methods were “unconstitutional.” Both local and federal agencies could be used to enforce the order.

At the end of January, the administration issued a new executive order called ‘Additional Measures to combat Anti-Semitism” that said it would tackle “anti-Semitic harassment in schools and on university and college campuses.” It vowed to implement a policy to prosecute, deport or hold accountable “perpetrators” who had participated in anti-Semitic harassment.

Also Read: One Woman’s Home Becomes a Lifeline for Palestinians Escaping War

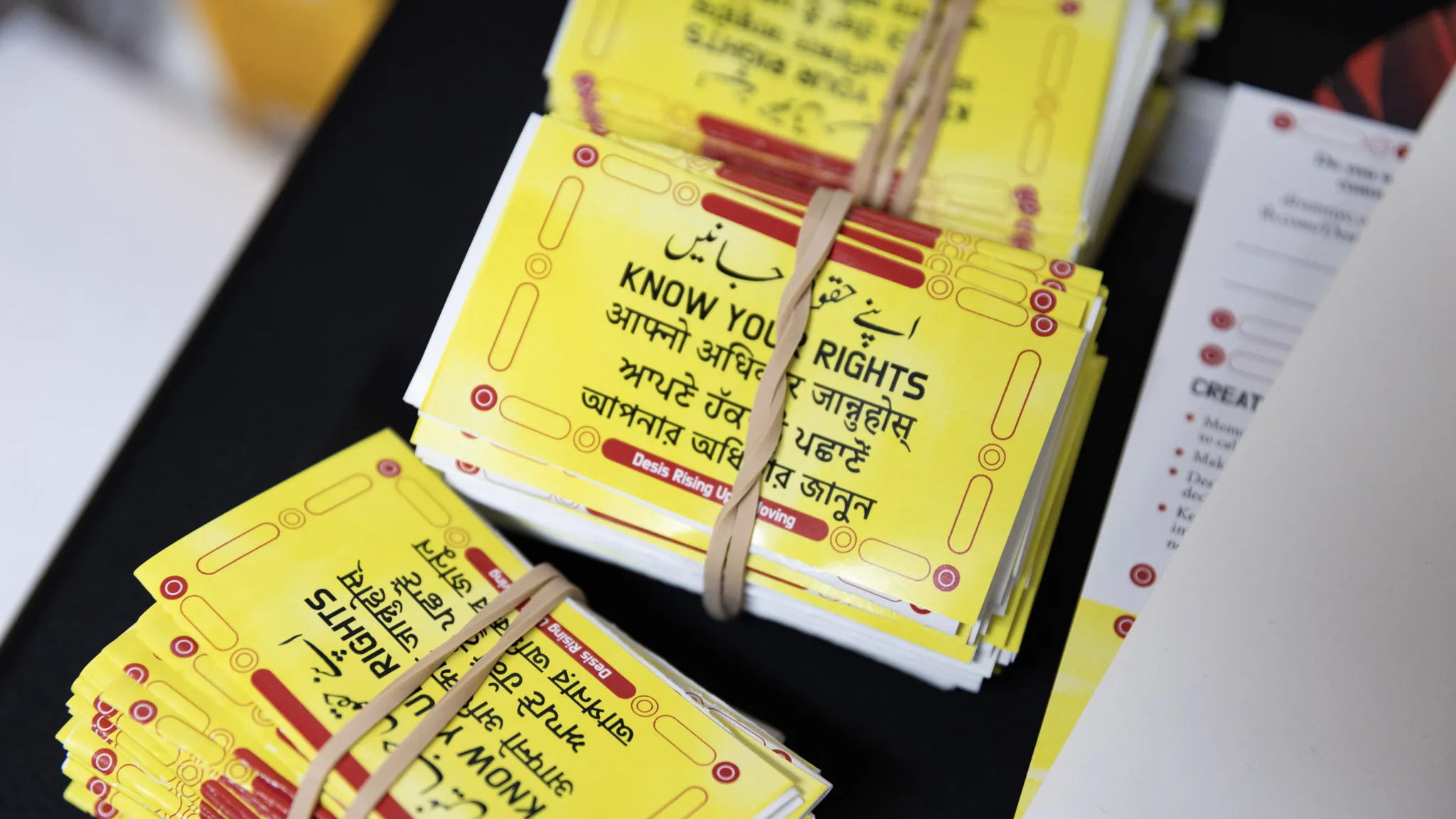

Mudassar Toppa, a staff attorney from CLEAR, a legal nonprofit and clinic at CUNY School of Law, said the new executive order targeted foreign students and academics, saying: “The executive order is meant to chill free speech and suppress protest in solidarity with Palestinians.”

International student Aman B., who participated in protests and asked to use the first initial of his surname only, expressed alarm at the new executive order. “Trump’s directives are being pulled directly from the Heritage Foundation’s Project Esther,” he said, referring to the national strategy instituted by conservative think tank The Heritage Foundation. “The far right is consolidating to spread its ideology. It’s ironic because the far right is the biggest spreader of antisemitism.”

When the Zionist youth organization Betar’s Twitter posted a threat on Jan. 29 to submit names to the Trump administration of students attending a vigil for 5-year-old Palestinian child Hind Rajab, who, along with the rest of their family, was shot in their car around 335 times in Gaza by an Israeli tank, B., also expressed concerned. “I think they are afraid and are trying to embolden the far right even more. It shows they are losing the narrative.”

“The administration realizes this is something bigger than students on visas,” said B., who attends graduate school in Manhattan. “I’ve been in the country for more than a decade, and I’ve never seen so many people brave enough to speak up.”

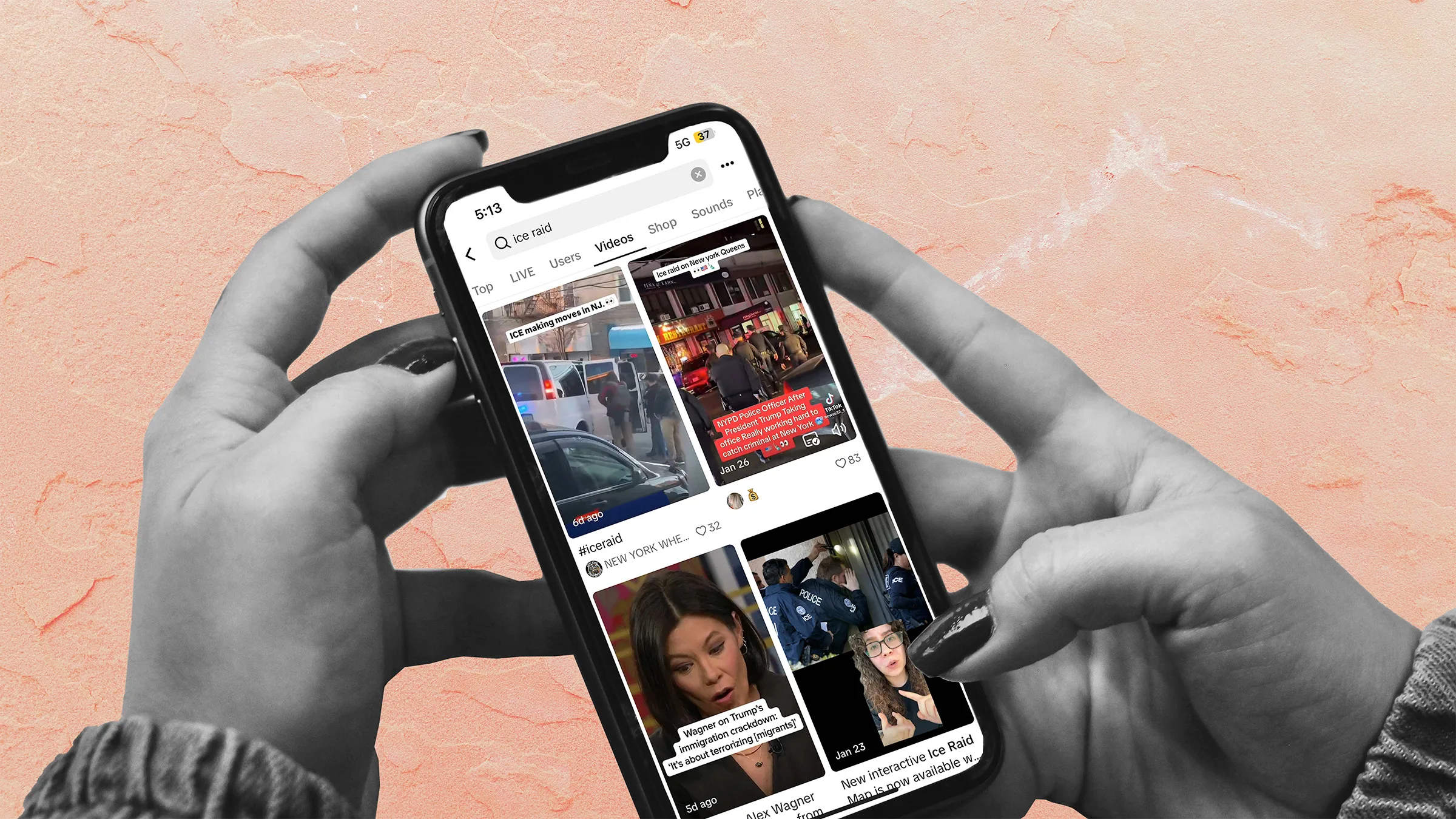

Since protests erupted at campuses across the city last spring, approximately 632 people were arrested in New York City, according to a tally created by the New York Times. Dozens of charges were brought.

A spokesman from the Manhattan DA office said he could not provide information about the number of charges because “nearly all cases related to the April 2024 protests are now sealed.”

While the new executive order targets students and academics, both Toppa and Harrison believe this is just the tip of the iceberg.

“It could also be used to harass and persecute foreign journalists, foreign news outlets, foreign authors, foreign faculty members who are here on academic visas or who are here as guest workers, engineers, computer scientists, technicians and researchers if their politics don’t align with the administration,” Harrison said.

Harrison believed the administration was being strategic by “issuing these executive orders in a quieter fashion than the original ‘Muslim Ban,’” which was so high profile it resulted in advocacy organizations, lawyers and courts all getting involved.

“Now you’ve got things flying under the radar, there aren’t massive protests, and there isn’t this huge civic engagement campaign to get people on board with opposing these policies,” Harrison added.

Harrison said he believes the under-the-radar approach was ultimately “more dangerous” because the programs were likely to get embedded once money was allocated and people were hired.

“Suddenly it’s this thing that’s been there all along and it’s impossible to get rid of. Then the argument becomes about scaling it back instead of canceling it all together when it never should have happened in the first place. The fact they can move a lot of this stuff into place and get it going without the public immediately getting outraged about it builds a little bit of inertia when the effort finally is ramped up to stop the program.”