Between 2016 and 2020, Diego Mejia worked for over three years as a porter and nonresidential janitor across two locations in Brooklyn. His tasks included cleaning, mopping, recycling and taking out the trash at one building, and handling repairs and painting and preparing units for new tenants.

“They [tenants] would call for leaks from the ceiling, and I had to be there to take care of it,” Mejia, 44, said. “I barely had time to spend with my family.” He worked an average of 90 hours a week, earning just $4.90 per hour — a violation of local, state, and federal labor laws — and never received overtime pay, he said. He noted that working on holidays and Sundays was common.

In September 2023, Mejia filed a lawsuit against the property management and owners for violations of minimum wage and overtime violations, as well as failure to pay wages on a weekly basis.

Janitorial workers who spoke with Documented reported regularly working over 40 hours a week without overtime pay, often earning below the minimum wage due to a law that sets their weekly compensation at a fixed rate of $10 per unit rather than an hourly wage.

While it’s unclear exactly how many workers fall victim to wage theft, Documented Wage Theft Monitor’s data reveals that over $5.3 million was stolen from janitorial workers in New York between 2012 and 2023. Studies also indicate that, like Mejia, most victims of wage theft in the industry are Latino immigrants and undocumented workers who do on average 70 hours of work per week. Workers like Mejia said the constant work keeps them away from their families, preventing them from taking time off and leading to working, at times, for half of the minimum wage.

Mejia arrived in New York from Honduras in June 2012. His brother in law, Hector Guzman, who lived at 425 E. 26th St. in Brooklyn, took him in. Guzman was the janitor for the building and asked Mejia if he could take care of the building while he was on vacation for a month. “He told me what to do for the maintenance and how to take care of the building,” Mejia said.

When Guzman returned, Mejia worked as a porter for five months before finding a job as a mechanic, a position he said he held until he was hired in 2017 as a porter by the property managers of the building at East 26th Street.

Also Read: Wage Theft: What to Know If You Think Your Wages Are Stolen

The managers offered Mejia $300 per week for 425 E. 26th St. and also asked him to clean a second building complex with two addresses, 351 Fifth Ave. and 355 Fifth Ave., for $200 a week. “I told them, what am I supposed to do with just $500 a week?” he recalls. They offered to eventually increase his pay to $800 a week, to which Mejia agreed.

However, he said the building managers only paid him $200 a month for the buildings at Fifth Ave. “I lost so much time in those buildings because they called me all the time,” Mejia said.

When he asked for a raise, he was told that the unit Mejia lived in at 425 E. 26th St. cost more than the salary he was asking for. “I told them, let’s do some math,” he said, adding he was often ignored.

On March 3, 2025, a settlement was reached between Mejia and the law firm representing the building’s owner. Documented reached out to the law firm representing 425 East 26th Owners Corp., United Management and Arthur Wiener, et al. in the lawsuit, but the firm did not respond to Documented’s request for comment.

Janitors — commonly called “supers” — are defined as workers who live in the buildings they service and are paid a fixed amount of $10 per unit. They are also provided with an apartment, free of charge, in the building they service, said Mel González, project director, employment law project at the New York Legal Assistance Group (NYLAG), the organization representing Mejia in the lawsuit. Those who do not live in the building are known as “porters,” explains González.

González said building owners and managers often pay janitorial workers on a weekly basis, extracting as much work as possible from the workers. Because the law limits their earnings at $10 per unit, the supers end up making less than the minimum wage required by the State of New York and the Federal government.

Like Mejia, González said that other clients have claims of working more than 40 hours per week, sometimes even 20 hours in a single day. He said the janitorial work’s demands often lead to excessive overtime, which requires workers to be available to answer tenants’ requests.

A 2007 report, Unregulated Work in the Global City by Brennan Center for Justice, found that non-union supers and supers hired directly by building owners or managers are more prone to minimum wage violations, earning, at that time, as low as $3.50 an hour, or less than half of the minimum wage that year.

Supers “will work for a combination of free housing (a room in the basement or an apartment) plus a low weekly wage; they are essentially on call round the clock, especially when caring for more than one building,” the report states, adding that the market value of the room that is provided to the supers “may not equal the minimum wage once hours worked per week are taken into account.”

“Landlords like to deny that supers are working all the time, even though we know from experience … supers are basically on call all the time.” It is unclear if supers qualify for sick leave and paid family leave, he added. “They can also be evicted from their apartments as soon as they are fired,” González added.

Roberto Galvez Ordonez, another client of González, filed a lawsuit last year alleging that his employer, 1280 Dean St. LLC, underpaid him for 11 years. The lawsuit states that Galvez Ordoñez “worked approximately 63 hours per week, yet his compensation fell far below federal and state minimum wage and overtime requirements.” The lawsuit states he earned approximately $4.39 per hour, below the federal minimum of $7.25 per hour, and $10.875 per hour for any time that went over 40 hours a week.

In 2022, Galvez Ordoñez also suffered a stroke while at work, requiring him to be hospitalized for four months and in rehabilitation for another three months. He said his employer rejected his efforts to communicate about possible accommodations. In 2024, two years later, the employer took Galvez Ordoñez to housing court and evicted him, the lawsuit claims.

Mejia says Galvez Ordoñez’ eviction story is not unique. In 2021, Mejia was cleaning the terrace of the building at 355 Fifth Ave. when the manager called him to go to 425 E. 26th St. to remove a large table from the lobby. Three days earlier, Mejia had seen a group of people use a dolly and a forklift to put the table inside, failing at the entrance of the elevator due to the width and heaviness of the table. “I told him it was impossible,” Mejia told the manager. “The table was so heavy; the glass was at least three inches thick.”

Despite his concerns, the manager insisted that Mejia and Guzman remove the table. As they attempted to lift it, the table fell toward Guzman and hit him on the leg, causing an injury that required eight stitches. Mejia suffered a back injury and chronic headaches that persist to this day, he said.

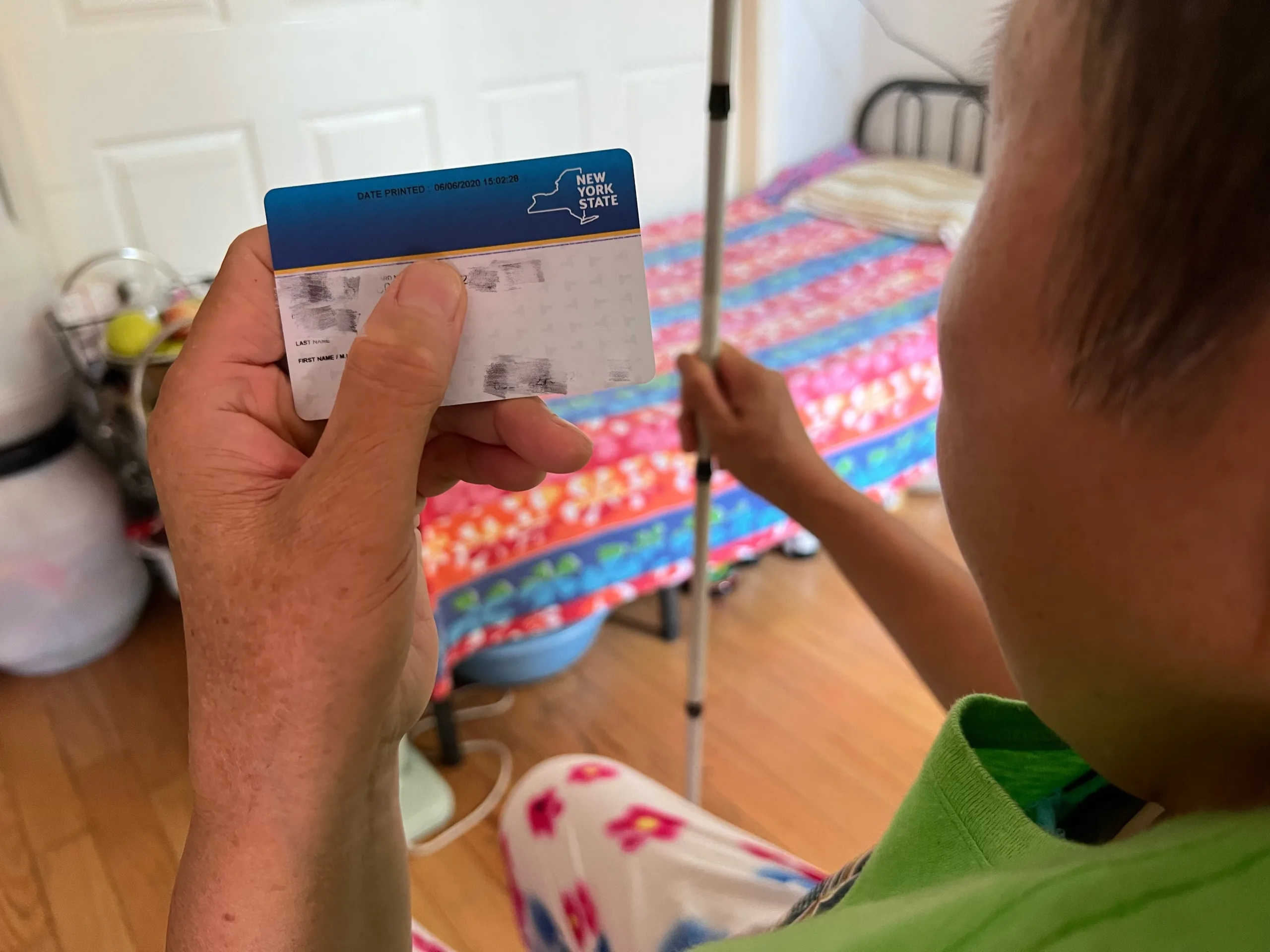

A month later, Mejia said he was let go. He filed for worker’s compensation but lost the case and was also taken to housing court. “Every week [the management] would send inspectors to say that my unit was illegal. They accused me of mistreating my children,” said Mejia, who now lives in North Carolina with his wife and four children. “I got tired of all the harassment, and I decided to leave.”

“There are companies that make people work in 8-hour-shifts, and they pay what is just,” he said, adding that he has to be careful not to move too fast due to the pain he feels in his back. “I want to be paid for the work I did.”