There seemed to be endless ways one could refer to Corky Lee.

There was ”the ABC (American Born Chinese) from NYC,” or the “Gordon Parks for the radical Asian American set,” and of course, the now iconic “Undisputed, Unofficial Asian American Photographer Laureate” which he had printed on personal business cards. But however eccentric, none could ever be considered a misnomer, only a testimony to Lee’s pervasive influence —a tenant organizer, a photojournalist, a community activist, a neighbor, a friend.

Lee passed suddenly in January of this year, due to complications from COVID-19. In the spirit of the late photojournalist, his expansive network of friends and collaborators channeled their mourning into a tribute to Lee’s life trajectory.

Last month, “Corky Lee on My Mind: A Photographic Tribute” opened at the historic Pearl River Mart, curated as an “homage” to Corky’s philosophy of “photographic justice” by artist and friend Chee Wang Ng, photographer and longtime partner Karen Zhou, and Pearl River President and friend Joanne Kwong.

The show features work by 21 photographers, from Lee’s contemporaries whom he worked with in the ‘70s at the Asian-American arts collective Basement Workshop, to his mentees, young virtuoso’s of Chinatowns across the country. The curators chose to omit Lee’s own work from the show, alluding to his presence through those he touched. Mostly, the images are depictions of various protests, gatherings, centered on the continuous fight over housing in Chinatown. In some, Lee is in the background, perched on a ledge or holding onto a light post, his face eclipsed by his camera, and the camera inviting us into the crowd.

To those that knew him, Lee’s work and the community were brought to life by each other. It seemed only fitting he be memorialized as part of the crowd. “Corky actually never forgot a face,” says Tomie Arai, a featured artist and a friend of Lee’s from Basement Workshop.

This aptitude for friendship is not only the linchpin to this exhibit, but the foundation for a community that has coalesced around Pearl River Mart over its five decade long fight to stay alive in a neighborhood constantly at war with real estate developers. A month before Lee’s death, Pearl River Mart was forced to downsize for the fifth time to a spot on Broadway, one of lower Manhattan’s busiest streets. For Kwong and the other curators, to have his legacy remembered in conjunction with the rebirth of Pearl River was necessary, and not the first time the trajectory of the store seemed to be in lockstep with Lee’s life.

Lee began photographing at the same time Pearl River was erected, during the window of time in the 1970’s when the ease of racial quotas invited an influx of Chinese immigrants to Manhattan’s Chinatown. Chen, the “grandfather” of Pearl River, and Lee lent each other a hand throughout the years, with the store’s struggles against displacement embodying the resilience of the AAPI community that first moved Lee to pick up a camera and document fellow tenant organizers.

“Corky often recalled that Mr. Chen lent him the Pearl River van to carry the lumber that became the Chinatown Health Fair, which eventually became the Charles B. Wang Community Health Center,” remembered Kwong, listing the now critical organizations of Chinatown that Lee either founded or helped to develop (CAAAV Organizing Asian Communities and the Asian American Arts Alliance are among the many).

In 2016, when Kwong joined Pearl River and decided to convert a cozy mezzanine space into an art gallery at their then new location in TriBeCa, she was introduced to Lee at the store’s opening and almost immediately asked if he would do a show. Lee had been the primary documentarian of Chinatown’s social and political movements for 45 years. His photograph of Peter Yew ignited a 2500 people march against police brutality; his documentation of labor revolts graced the cover of the era-defining classic Forbidden Workers; yet this would only be Lee’s second solo show, the first almost two decades prior in the dingy second floor of the Museum of Chinese in America.

“He could have just forgotten. But he called me the next day and said, we have to start planning,” recalls Kwong. “I remember looking through his work and every five minutes, I’d ask, how come you don’t have a book? How come the documentary isn’t finished?”

Lee insisted the show be titled “Chinese America On My Mind,” an ode to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s controversial 1969 exhibit “Harlem On My Mind.” This choice, an inadvertent jab at elite art institutions that would never recognize the subjects of Lee’s work, and at the failure of these institutions to properly represent the history of struggle in communities like Harlem, was indicative of the subtle humor Lee carried. Whether in a one hundred year old museum, or in the “tea parlor” of an eclectic department store, Lee’s images never wavered from his core assignment: to deliver, as he put it, “photographic justice.”

“The motivation was, at least for the general public, if not the Asian Americans, to see that they were part and parcel of a community,” explained Lee at the opening of his 2016 show, again citing his early years as a tenant organizer, where his photographs gave voice to the community’s struggles.

“Especially in the ‘70s in Chinatown, it’s not like if tenants are going to protest landlords, the New York Times would be there,” remembers Alan Chin, whose image “Corky We Love U” closes the current show at Pearl River and who first encountered Lee’s work when he was 12-years-old growing up in Chinatown. He went on to be a photojournalist for the New York Times and met Lee in 2001, when on assignment to photograph Lee.

“TV news wouldn’t even be there, because they wouldn’t know about what was going on in Chinatown. Corky shaped that, and gave Chinese Americans a way to see themselves.”

Lee’s life was measured by the depth of his relationships, and the opening night of “Corky Lee On My Mind” felt like spying on an intimate dinner party, passing artifacts across the table, referencing shared memories, nudging at inside jokes. In actuality, the crowd also included people who knew Lee only through the pandemic, a year when the AAPI community was never more simultaneously visible and invisible.

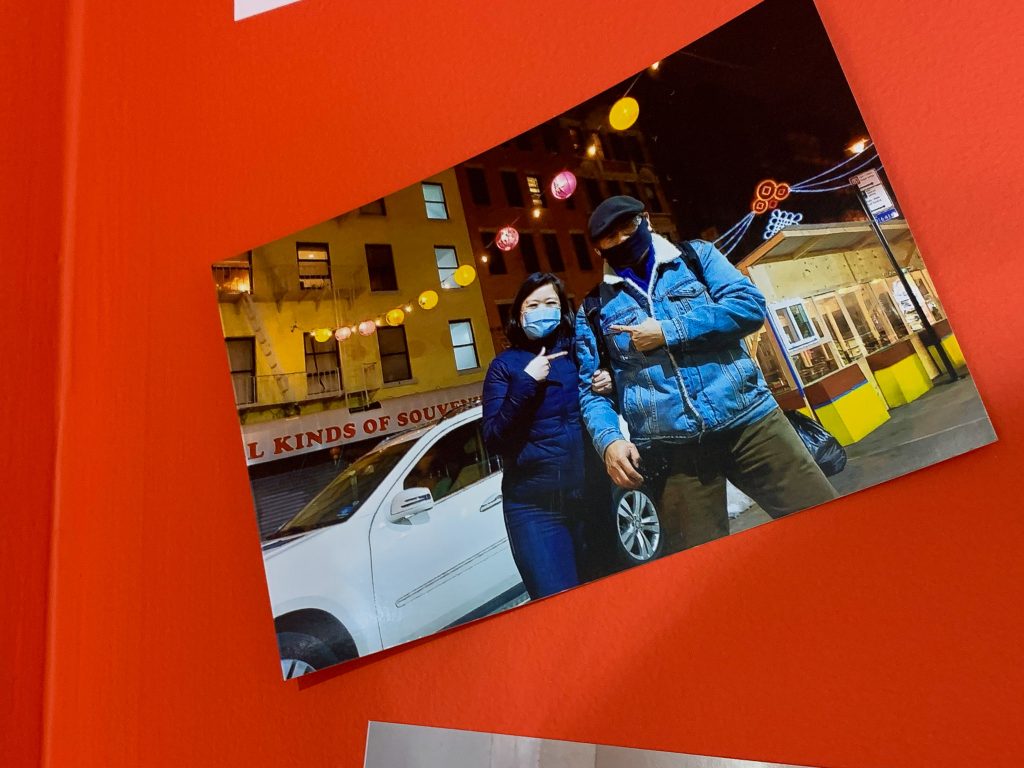

In the waning months of the photographer’s life, he’d become a street patrol volunteer after the rise in Anti-Asian harassment, and helped prep hundreds of lanterns for Light Up Chinatown, passing a few weeks after the installation went up on Mott Street. “We had these volunteers in their 20s and 30s and Corky was right there with them,” recalls Kwong. “He was so consistent. Every time we had an event, he would show up. He would drop by a week or two after and bring printed photos for me. He would always sign the back. A few times he would include a flash drive. I learned after that that meant he trusted you.”

In the months after his passing, Lee’s presence reappeared not just in this show, but in the working people of Chinatown’s cyclical fight for justice, and the continued preservation and ownership of their neighborhood.

补偿终止但盗窃不止!纽约近9千起粮食券被盗案难获赔

In February, workers from Jing Fong, Chinatown’s largest dim-sum restaurant, and the only unionized shop in the neighborhood, began their twice a week picket against a landlord that foreclosed the dining hall; in 1995, Lee captured workers picketing Jing Fong over wage theft. In April, the City’s appeals court gave the greenlight on the Chinatown jail expansion that would have adverse environmental effects on the neighborhood; in 1982, Lee photographed a mass protest against an identical development plan.

“Because Corky laid the foundations for the way that we see ourselves, and was the first to believe in our strength” Arai reflected. “We can continue to toy with the question of what it means to be American.”

Left: A photo Corky Lee took during a 12,000 person march against the construction of a jail in Chinatown in 1984. Right: Lee taking photos at a Town Hall held at PS 124 in 2018 where Chinatown residents discussed Mayor de Blasio’s plans to develop a jail in the neighborhood. Still form a video by Tomie Arai.

Corrections: This article was amended to specify details about Pearl River Mart and Lee’s relationship to its founder.